|

|

|

Photo courtesy of Billy Black |

In a bitter storm on the North Atlantic in 1992, Minnesota racer Mike Plant disappeared under mysterious circumstances in his new racer, Coyote. In an exclusive, Northern Breezes is publishing a five-part serialization excerpted from the new book, Broken Seas. This is Serial 2 of 5 series. (Part 1 began in the April 2005 issue of Northern Breezes.)

The

PASSION

of

MIKE

PLANT

America’s greatest solo sailing hero takes his final ride in Coyote

By Marlin Bree

Copyright 2005

From Broken Seas

|

|

|

Photo courtesy of Billy Black |

|

He was now America’s premiere single-handed sailor and he had come out of nowhere in only six years. In France, he got the nickname of “Top Gun” for his passion for carrying sail in heavy seas and wild winds.

It seemed that there was little Mike couldn’t do or survive. A certain mystique surrounded him. He had savvy, capability, and endurance, honed on the oceans of the world. He came to love the solitude and the challenge of single-handed, long-distance sailing. He was happiest when he was alone at sea with his boat.

When family and sailing friends didn’t hear from him, they knew it was because he was into “his racing mode.” They’d hear from him when the race was over. He was passionate about his boat, his race, and his dream.

But the challenge was getting harder. To compete in the 1992-93 Vendee Globe Challenge, Mike would need as powerful a boat as he could get to keep up with the aggressive, and better-funded, French racers. The boat had to be strong and above all, it had to be fast.

Once again he turned to Rodger Martin to design a breakthrough boat, a racer ahead of its time. Mike knew what he wanted and he had more than a handful of ideas.

Another around-the-world sailor, Dodge Morgan, who was the first American to sail alone nonstop around the world, had an ominous viewpoint: “Mike had a boat designed close to the edge and built perhaps a little closer,” he was quoted as saying in news stories. He added, “Mike knew what he was doing and so did the people who worked with him. They wanted to win a race.”

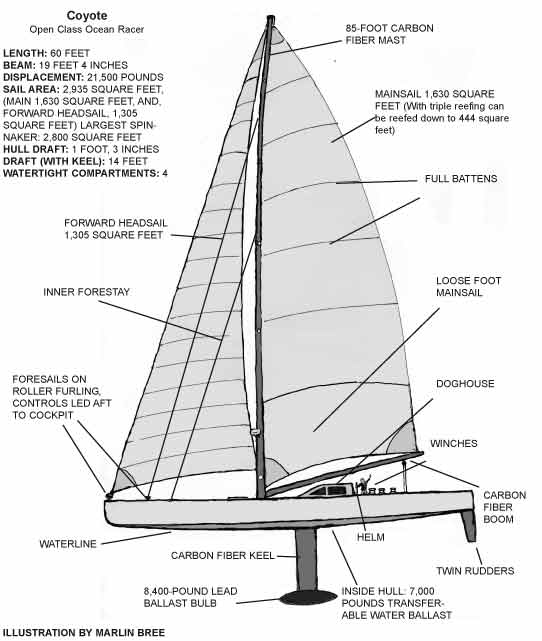

Coyote was designed to be a flat-out super boat, a high-performance ocean dragster powered by a huge sail area and a knife-blade keel, designed to do only one thing: rip around the world single-handed at top speed and to win the Vendee Globe Race.

At 60-foot overall, Coyote was a skimmer that could soar over the waves, rather than plow through them. With a menacing plumb bow, flat transom, and straight sheerline, she projected brute force. “Beautiful, but with a raw, brutal type of beauty,” Coyote’s sail maker, Dan Neri, described her.

But for other sailors, Coyote looked like a “monstrous boat.” “That thing is an animal,” one man said, pointing out, “that boat could be difficult to handle with a crew of ten on board.”

She was beamy for a sailboat at nearly 19 feet 4 inches in width and flat on the deck, like an “aircraft carrier,” as her naval architect sometimes joked. She had a low freeboard, which meant she had little wind resistance, but that also would make her a wet boat. She could catch and fling back the waves she couldn’t fly over. Incredibly, Coyote’s 60-foot hull itself only drew 1 foot 3 inches of water.

Inside, you had to squat to move around, for she only had 4 feet of headroom, except in the small doghouse, which had a headroom of 6 feet.

Mike was a fanatic on lightness, since less weight to drag around equated to a faster boat. With her E-glass set in epoxy over foam-core construction, Coyote was a strong but ultra-lightweight flyer. She would displace only 21,500 pounds, nearly 6,000 pounds lighter than Duracell, which had an approximate average speed of 11 knots.

Coyote would also set approximately 50 percent more sail area than Duracell, a small cloud of 2,935 square feet of sail (based on a forward headsail of 1305 square feet and full mainsail), on her 85-foot carbon fiber mast. Her main alone was 1,630 square feet and it weighed 250 pounds. This sail took a lot of muscle and stamina to raise and handle, even on a 2- to-1 halyard and a powerful winch. To raise the mainsail from the boom to the top of the mast would take Mike about 10 minutes of hard work. Her largest spinnaker was 2,800 square feet.

Like most of her class of ocean racers, she had a very long fore triangle with her mast set back at more than 50 percent of the waterline, so that she could carry an effective inner forestay. Dan Neri explained, “It is not practical to change headsails with one man on a boat that big, so they use a reaching/light wind headsail on the forward stay and a heavy air jib on the inner stay.” Both foresails were set on furlers, with controls leading back to the cockpit.

Her mast was hollow, built of braided carbon fiber and glass, and very light at about 3 pounds per foot for its 85-foot tall height. With its advanced triple-spreader design, it was thin and flexible and would need attention to keep it properly tuned and in column. But it would be fast.

To carry that much power in her sails, Coyote had a 14-foot deep “knife blade” keel for minimum resistance while ripping through the world’s oceans. At 40 inches in length and 6 inches in thickness, the keel was strongly built with 42 layers of Kevlar and carbon fiber. The carbon fiber fin encapsulated a heavy stainless steel plate at its bottom, to which the bulb was bolted. Six heavy stainless steel bolts extended through the plate and the bulb, and were secured with nuts. The whole unit was overlapped with 15 layers of carbon fiber for extra strength.

At the bottom hung a torpedo-shaped lead bulb that weighed 8,400 pounds. It was 112 inches long, 18 inches high and 27 inches wide.

Coyote also could carry an extra 7,000 pounds of transferable water ballast in two tanks, so she could get extra weight on the windward side to keep her level on a wild reach. For safety, she had 5 air-tight compartments for floatation and she was designed and built as strong as possible, with special attention to impact strength. With her Airex foam core hull, she would have enough inherent floatation to remain afloat even if she was holed and her hull flooded with water.

Mike’s Coyote would be the most extreme 60-foot monohull ever launched in the U.S., the ultimate weapon to race nonstop around the world.

“Coyote met and surpassed her advance advertisements,” wrote Herb McCormick. “She was the fastest, wildest, wettest monohull that I have ever sailed.”

When I met him at the Minneapolis Boat show, Mike told me that funds were very slow in coming in. He was not a wealthy man and he hoped to rely on sponsors and other financial help to get his racer built. Financing the boat was a big concern: big, custom racers like Coyote could cost a whopping $650,000 to $800,000, and sometimes more, a lot more, depending upon what exotic materials you wanted to put into them. To race successfully, you couldn’t scrimp. You needed the exotics.

He talked about doing a book with me, but that project faded when we discussed the time required to write and to publish a manuscript. Mike just didn’t have the time.

He was faced with a multitude of construction details on the custom-racer being built at Concordia Custom Yachts, of South Dartmouth, Mass. He was not a sailor to place an order with a yard and then show up when the boat was ready. It was his racer, and from his extensive racing experience, he had specific things in mind.

“Mike knew what he wanted and he had a great understanding of what the boat would be put through,” Dan Neri said. Dan went with Mike to the boatyard several times when the boat was being built. “Mike was deeply involved in the decision making for the assembly of the structural parts of the boat,” he said. “Some of those decisions were made on the fly, to the point where Mike was drawing on scraps of plywood to illustrate his ideas.”

The boat was in a “slow-build” program: the yard started it, and built it, on and off, as Mike came up with money. “Mike was a hands-on man in everything he did,” Dan said. “He was trying to manage the boat build, mast engineering and construction, sail inventory planning, electronics installation, fund raising and preparations for sea trials and ultimately his campaign for the Vendee Globe. He had a charisma that drew people to his cause and there was a small army of people in Rhode Island doing what we could to help him out. I am sure many of us have thought we should have pulled him aside and tried to talk him into slowing down.”

But that was not to be. “With Mike there was no indecision,” Dan said. “Everything was about meeting the next goal.”

Coyote was intended to be a high-tech, custom-built dreamboat racer using the best of everything new. Dan said, “Mike brought together his team of friends and associates and this very state-of- the-art race boat was built by craftsmen relying on their best instincts and experience.” He added, “In some areas, the design was beyond that experience base.”

“The team at Concordia were among the best in the business,” Dan said. “If any group could pull off this build project, it was these guys, and at the time, a seat of the pants approach to high-tech yacht building was not so unusual. But looking back on it, we were clearly pushing too close to the limits of the materials.”

Instead of an early 1992 launch, followed by leisurely sea trials in fair

weather on the North Atlantic, the boat came off the ramps September 10 – six

months behind Mike’s original schedule. The critical keel to bulb assembly was

completed only days before launch date.

He had only 7 weeks to get the boat ready and to be in France for the race.

The power of Coyote was phenomenal. She accelerated quickly and on a reach she tore across the water like no other boat Mike had ever sailed. Her cruising speed was calculated at 18 knots – practically flying.

But as Dan Neri pointed out, “there are considerations for handling an extreme boat like this.” At 60 feet in length, Coyote was no sailing dinghy and Dan said, “you plan about 4 steps in advance, but focus on the next step at all times.”

Because Coyote had no engine, the big boat was towed by an inflatable powerboat when docking or departing. Getting her underway was a little difficult, though, because the mast was fairly far aft. “The boat actually wanted to sail backwards with just the mainsail up,” Dan said. “For that reason it was important to keep it going forward at all times, no different than most big boats.”

With Dan aboard, Mike tested Coyote off Newport in Rhode Island Sound.

“My most vivid memories are of looking up the rig while fetching in 25 knots of wind and the boat crashing along at 11 knots,” Dan said. “The mast lacked torsional stiffness for some reason. Either the tube did not have enough off-axis wraps, the spreader geometry was wrong, or it did not have enough shroud tension. The mast moved more than any rig I had seen before or since. The mast was built in 4 sections, which were joined at the boat shop. Mike had a set of alloy spreaders that I think were supposed to be used for the mold to make carbon spreaders, but they were used on the mast instead. So it was a big, high load spar system built, again, by a group of excellent composite boat builders, but without the benefit of the level of engineering we are accustomed to today.”

Dan recalls that Coyote was “incredibly loud inside” when sailing with the breeze forward of the beam. “It was also very loud off the wind, but the off-the-wind noises were not as alarming,” Dan said. He later explained: “Today, we are used to the noise, but with Coyote being the first of its type, the noise was new and a little unnerving.

“The best day of sailing was during a photo shoot off the mouth of the Sackonett River,” Dan recalls. “There were long ocean swells from a low pressure system well offshore and a 20-knot sea breeze. We had a kite up, surfing in the high teens, and, all of the crew inside the boat so the helicopter could film Mike sailing it alone. Davis Murray, Mike’s buddy from the Virgin Islands, was steering with the autopilot while looking out the windows. As a joke, Davis made the boat bear off at the bottom of a trough while Mike was standing on the bow in the hero pose with one hand on the head stay. The bow dug in and the wave caromed back along the foredeck and slammed across the window. When the water cleared, Mike was standing there, drenched and smiling. We did it again. This time, Mike held on to the head stay with both hands and let the wave pick him up so that his whole body was streaming aft, parallel with the deck.”

Crew high-jinks aside, Coyote was proving herself as a remarkable boat.

“Coyote tracked quite well,” Dan said. “All of Rodger’s boats sail great off the wind. The heeled water plane is close to symmetrical so the boat wants to go in a straight line. There is actually plenty of keel area and it is efficient so there is always attached flow. The leeward rudder is vertical, or both are working at lower heel angles. The rudders are balanced so there are fewer loads on the autopilots. The boat was much more kind on the pilots than more ‘conventional’ boats that become less balanced with heel. The boat could be sailed for days at a time under autopilot. Obviously the sail plan has to be set up correctly. If the boat is overpowered it will behave badly.

“Compared to a heavy displacement boat, I would say that Coyote felt like she was on rails most of the time. The boat was very fast and with speed you get directional stability. The flip side is that if the autopilot wanders too far, a fast boat can take a quick turn toward the wind. Steering problems are usually a function of the sail trim and pilot setup rather than the boat design.”

As they tested the big boat, Mike discovered a few problems. As Dan relates: “Coyote did not go to weather as well as a typical fully crewed race boat. The hull shape is optimized for reaching and running. In a long distance ocean race, the only times you want to be hard on the wind is when you have to while leaving harbors and approaching harbors. Otherwise, you sail a slightly more freed-up angle toward a more favorable part of the weather system, or the next weather system.”

Mary Plant minced no words. When going to weather, she said, “of all the boats Mike had, Coyote was the most miserable.”

Mike and his crew discovered during sea trials that when Coyote

reached a speed of about 9 knots, the keel’s foil and bulb began to create a

humming sound. The crew checked out the keel through the sight glass – a piece

of Plexiglas through the hull to see the keel while the vessel was underway –

but they couldn’t see any problem. In addition to the noise, they felt a

vibration coming from the keel. As Coyote’s speed increased, the sound

and the vibrations would change. Mike dismissed the noise and vibrations as

problems common to racers like Coyote.

Overall, Mike was happy. His new racer performed brilliantly and he worked hard

to learn her special ways. But the harder he worked, the further he seemed to

fall behind.

Mike was a list keeper and at one time, he said that the he had a million things left to do before he left. He confided to a friend that his list was “so long now, I’ve lost the beginning of it.”

In the next serialization:

Coyote was a superboat, all right, and to show her off, Mike sailed her

to a boat show. In the Chesapeake's muddy bottom, Coyote ran into deep

trouble when she ran aground.

Excerpted from Marlin Bree's new book, Broken Seas: True Tales of Extraordinary

Seafaring Adventure (Marlor Press, 2005). Visit his web site at

www.marlinbree.com.

Continue The Vision

The Mike Plant Memorial Fund was established to provide a sailing experience for

inner city kids. Donations can be made to:

Mike Plant Memorial Fund

in care of the Wayzata Sailing Foundation

P.O. Box 768

Wayzata, MN 55391

Visit www.wayzatasailing.org/mikeplant for more information.