|

|

|

Photo courtesy of Billy Black |

In a bitter storm on the North Atlantic in 1992, Minnesota racer Mike Plant disappeared under mysterious circumstances in his new racer, Coyote. In an exclusive, Northern Breezes is publishing a five-part serialization excerpted from the new book, Broken Seas. This is Serial 1 of 5 series.

The

PASSION

of

MIKE

PLANT

America’s greatest solo sailing hero takes his final ride in Coyote

By Marlin Bree

Copyright 2005

From Broken Seas

|

|

|

Photo courtesy of Billy Black |

|

PROLOGUE

It was all so promising. He had sailed through hurricanes, dodged icebergs,

fought six-story high waves, and even survived a capsizing in 45-foot seas in

the Indian Ocean. He was America’s most accomplished single-handed offshore

sailor and, after three daring circumnavigations, Mike Plant was now starting a

fourth voyage with his bold new sailboat.

Coyote was designed to race nonstop and unassisted around the world – a circumnavigation of nearly 24,000 miles in one of the most demanding sea races ever conceived.

At 60 feet in length and flying a cloud of sail atop a huge black mast, Coyote was a brute, the most awesome racer Mike had ever attempted to run in the Vendee Globe Challenge. She was Mike’s passion; he was gambling everything on her.

Coyote hit the water only weeks before he had to shove off on a late-season run across the North Atlantic. Mike had been a one-man band trying to get her shaken down, put her through sea trials, and get her equipped and provisioned for more than 100 days at sea on the most dangerous oceans of the world.

With only 15 days left, Mike set sail alone out of New York harbor,

pressing his new boat hard against the edge of an oncoming storm. He needed to

cross the North Atlantic to meet his deadline at Les Sables d’Olonne, France,

about 3,200 miles away.

But then the voyage began to go horribly wrong.

From official records and from a reconstruction of possible events, we can build the story of Mike’s final voyage.

Midnight in the middle of the North Atlantic: Coyote’s deeply reefed mainsail

and sturdy storm jib caught the sudden North Atlantic gust. Spray flashing from

her bow, the big racer dug her lee rail in, careening into the wave’s dark

trough. She picked up speed all the way down.

Mike Plant braced himself against the giant wheel, jubilantly feeling his big racer’s power. The boat began to vibrate and shake; the twin rudders’ high-speed hum became a high-pitched scream.

From behind the great machine, a rooster tail of water shot skyward. Coyote’s sharp bow slashed into the oncoming wave, cutting deep. A torrent of ocean rolled back over the deck, slapping Mike in the face.

A thin smile crossed his lips – despite all the odds, despite all the troubles, he was on his way at last across the stormy North Atlantic.

His beauty of a boat, Coyote was alive in his hands, surging through the heavy seas with speed and vitality. Her sails, hull and rudder all had messages for him. The big boat told him what she felt and what she wanted to do. He was her keeper and she was his best friend.

Tonight on the Gulf Stream, he had almost no visibility. There was danger in the boat’s tremendous speed and the oncoming black waves that roared as they got closer and loomed large as islands.

Mike was bone weary, cold and wet.

There was no rest ahead, either. He had to tough it out this raw November night to hand steer because of his boat’s electronics failure.

He’d been hand steering his giant racer for eight days.

Because he had no electricity, he had no automatic helm to give him any relief in the storm waters. He had no lights onboard and his navigation system was out.

But he took joy in the fact that Coyote was moving well. In his hands, she felt solid and good.

They’d push on – hard. That was their style.

It was the only way to win races.

The 41-year-old sailor was bound for Les Sables d’Olonne, France, to enter Coyote in the Vendee Globe Challenge single-handed race around the world.

They had left New York October 16 and were gunning to get in under the wire to meet the skipper’s deadline of October 31. The 3,200-mile dash across the North Atlantic was his first ocean shakedown alone in his new racer.

He’d use use the run to qualify Coyote for the ocean race.

Before the electronics went out, he’d had other problems he thought they’d overcome. During trials, she had run hard aground twice in Chesapeake Bay.

She seemed all right at first, but he had detected a slight vibration somewhere down below from the area at the tip of his radical 14-foot deep keel, with its 8,400-pound lead ballast bulb. It had kept Coyote sailing flat out into the teeth of the storm, eating up the miles.

If he just got her across the Big Pond, there’d be plenty of time to haul her and inspect the keel and bulb. His crewmembers, who had flown on ahead of him, were waiting for him.

The shores of France beckoned.

Coyote caught a blast of cold air and lunged down another wave train.

Mike gritted his teeth, his arms aching.

The big racer heeled precipitously, one of her twin rudders out of the water.

Mike could feel the boat straining and creaking beneath him as every sail, every line, every winch loaded up at maximum pressure.

Twelve...Fourteen knots. He had to estimate the speed. The boat was fantastic!

Suddenly, he felt an odd motion.

The hull vibrated and the deck slammed under his feet.

Mike gripped the wheel. Something was awfully wrong.

In the dark, from below came a low rumble, like that of a freight train.

A sudden shuddering shot through the hull.

Rudder groaning, Mike spun the wheel.

But there was no holding her now.

Coyote canted dangerously, her windward side rearing up, her mast reaching down into the the fury of the waves.

There was a dull cracking noise – and the dark seas rushed up with terrible finality.

Mike Plant was an American original: he came out of nowhere on the international racing scene and in a few short years stood on the threshold of greatness and fame. He had incredible focus and drive, even before he got into the unique, and uniquely dangerous sport of solo long-distance ocean racing.

He loved adventure. “I think Mike was born with this spirit,” his mother, Mary Plant, recalled.

Born in 1950, Mike grew up along the shores of Minnesota’s Lake Minnetonka, on the western edge of Minneapolis. “We were fortunate to live very near the Minnetonka Yacht Club,” Mary said, “and all the children went to sailing school. Mike was the only one who really took to sailing.”

The Plants bought a second-hand X-Boat and Mike would go out many times on his own just to sail around the lake. Mike called his boat, Lucky Strike.

“He was very focused,” Mary recalled, “and always working on the boat, changing gear and improving little things.” He was a good sailor and by age 12 he was winning races.

“Mike loved challenges,” his mother recalled. “As a young boy, he was always thinking of things to do and loved hands-on projects. He built a one-person boat with a motor and he’d scoot around close to shore.

He built a small shack near the water’s edge where he and a group of neighborhood kids would sell candy and pop. They would round up old boats and fix them up in hopes of selling some.

“Mike was a ‘doer,’” Mary said. “The spirit of adventure came as he got older. He was full of action.”

But he also had a problem. When Mike was two years old, his mother saw him hold various items up close to his eyes to look at them. Concerned, she took her young son to see an ophthalmologist to have his eyes checked.

“As it turned out, he was very near sighted,” Mary said. “He started to wear very thick glasses and was later termed ‘legally blind.’ In his early teens, he began to wear contact lenses.

I first met Mike in Minnetonka, MN, when he was an instructor at Minnesota Outward Bound. By age 18, he had been teaching survival and team building through wilderness adventures programs.

He was making a name for himself as an adventurer and a survival specialist. He hiked from his home in Minnesota down through South America to the tip at Tierra del Fuego, a distance of 12,000 miles, largely on foot.

“How could you do that?” I asked. A lone American, hiking through remote provinces and dangerous jungles, could have been easy prey for bandits and mercenaries.

“I didn’t have anything they wanted,” he told me.

Mike took naturally to Outward Bound. The organization was conceived in Great Britain during World War II, when many British seamen unaccountably died at sea while awaiting rescue after being torpedoed by German U-boats. The program was designed to instill self-reliance, spiritual tenacity and to develop innate abilities to help seamen survive under difficult conditions.

These were lessons Mike learned, taught others and believed in himself.

After leaving Minnesota-based Outward Bound, boating attracted him once more and he traveled to Lake Superior, where he bought a used 30-foot Cheoy Lee sailboat at Bayfield, WI, near the Apostle Islands. He sailed eastward across Superior, through the Great Lakes, down to New York and out into the North Atlantic to St. Thomas, in the Virgin Islands. Throughout the winter, he lived on his boat in the islands and did some contract work, primarily as a carpenter.

When spring came, he sailed northward with a friend, but neither knew where they wanted to go. His friend suggested they go to Newport for the Newport-to-Bermuda sailboat race. They saw the start of the race and Mike remained in Newport, working as a charter skipper to deliver other boats to ports in the U.S. and the Caribbean. Between assignments, he earned money doing carpentry and house painting.

But in 1983, he told me, he saw a film about an around-the- world sailboat race that “changed my life.” It was the 1982 – 83 BOC Challenge, a yacht race for around-the-world solo sailors.

It was an epiphany. Suddenly, he knew what he wanted: be a long-distance sailboat racer.

“When I walked out of the theatre,” he explained, “it was like a light switch had gone on. I’ve never really looked back.”

It was a long way between dreaming about being an ocean racer and actually getting a boat to enter a race. The nautical competition was fierce and the around-the-world sailboat races were dominated by the well-funded European syndicates – especially, the French racing super stars.

Their boats and their skippers seemed unbeatable.

Undeterred, Mike told his mother, “I’m going in the next race.”

He began building his first blue-water racing boat on a shoestring budget in his front yard evenings and weekends, while he worked days as a building contractor. Friends pitched in to help him build a 50-foot water ballasted sloop, working from a new design by Rodger Martin. Mike was the naval architect’s first customer.

Somehow, with his home-built boat, Mike hoped to compete against the world’s top racers, their multi-million dollar designs, and their well-honed racing programs.

He took his boat to the starting line in Newport in 1986 for the BOC Globe Challenge, in which solo sailors raced their giant sailboats 27,550 miles around the world, with only three stops. As he set off in Airco Distributor, all three of his autopilots failed, one by one. That meant he had to hand-steer all the way to the next stop, but Mike kept going. “I’m not going to turn back,” he radioed.

Mike’s home-built Airco Distributor circled the globe in a total elapsed time of 157 days 11 hours and 44 minutes, bettering the previous record by 50 days. He won his class.

The international racing world took notice. A lone American had become one of

the world’s most successful single-handed offshore sailors. Moreover, he had

done it on his own terms and he had overcome enormous obstacles.

Around the old sailing port of Newport, Mike was no longer another boat bum and dreamer. He was a fire-in-belly skipper, a real racer. And he had only begun to fulfill his dream.

In 1989, the Vendee Globe Challenge was conceived as nothing less than the ultimate ocean racer’s race: a challenge to race solo around the world, without stops for rest or reprovisioning. Racers would not be able to get outside help. The brutal, nonstop marathon would run 24,000 miles, west to east, rounding the earth’s most dreaded capes, including the fearsome Cape Horn and the misnamed Cape of Good Hope. He’d not only have to survive the horrors of the Southern Ocean, but have to carry sail as long as he could and race across it.

This was truly the ultimate race and it represented a gigantic new challenge. It also meant a new boat for Mike. Again, he turned to his friend, Rodger Martin, for a design to speed him round the world nonstop. And to win a race.

Mike had to dig deeply into his own meager resources to build his boat. In the U.S., he could not get enough sponsors to fund his racing challenge.

He began construction of his 60-foot boat in a rented shed. Duracell would have twin rudders, a super-fast hull and state-of- the-art water ballast. Mike sailed the boat across the North Atlantic to France to qualify and after the race began, soon became the early leader, despite suffering for a week from a virus infection. He toughed it out and got well at sea while he raced.

In the Pacific Ocean, disaster struck: a $5 part broke on the rigging. Mike had to sail 36 hours straight until he was able to anchor off Campbell Island, New Zealand. A storm caught him and began pushing the racer toward a rocky shore’s certain destruction.

On the island, four meteorologists saw the racer’s plight and motored out in their Zodiac. To save his boat with its dragging anchor, Mike had to accept the tow, but he knew that the outside assistance would disqualify him.

The meteorologists suggested to Mike that he simply continue the race. They

vowed eternal silence. No one would know.

“Except I would,” Mike answered.

Mike radioed the race committee that he had accepted outside help and that he would continue the race, though disqualified. He unofficially crossed the finish line in seventh place.

Mike lost the race, but to the admiring French, he emerged a real hero. His determination and honesty did not go unnoticed: 25,000 people lined the breakwater in Les Sables d’Olonne to give him a rousing hero’s welcome. Mike was the only American in the race.

Herb McCormick, editor of Cruising World, and the Boating Editor of the New York Times wrote: “The tens of thousands of French men and women who greeted him at the finish understood something that largely was missed in this country. By forging on, by completing what he’d set out to do, by showing the highest respect for his competitors in a wonderful act of sportsmanship, Mike was as much a winner as the sailors who’d officially crossed the finish line.”

Despite delays, Mike set the American record for the shortest time to circumnavigate the world single-handed. He did it in 134 days.

In 1990, he entered an upgraded and modified Duracell in the BOC Challenge, again setting sail from Newport. His effort caught the attention of Minnesota Senator David Durenberger, who read a section of a New York Times report into the Congressional Record. He noted that Mike was the only American in the single-handed, around-the-world, nonstop yacht race that was regarded by sailors as “the ultimate test of courage, stamina and resourcefulness.”

As Duracell neared Cape Town, South Africa, in the 6,800 mile first leg of

the race, Sen. Durenberger read into the Record: “After 35 days on the open

seas, fat igue has become Mike’s constant companion. Mike has slept in his bunk

only twice during the trip. His daily sleeping routine is to work and sleep in

20-minute intervals...Hundreds of miles from the nearest shore, Mike is now

running low on food. Most of his remaining food supply exists in the form of

carbohydrates and starches, namely beans and rice. But Mike and the Duracell are

likely to overcome their obstacles and regain lost ground during the next two

legs

of the race. It is in these two legs that the winds above the southern seas are

stronger than in any other part

of the race. As Mike traverses through the turbulent seas below the equator, the

spirit of Minnesota will go with him.

“Mike thrives on the inter-relationship with nature that solo, offshore sailboat racing provides. He once said that offshore sailboat racing ‘strips you to the soul–exposing who we are, what we are (and) why we exist.’ To Minnesotans and Americans alike, Mike’s courage, leadership, and the ability to overcome adversity symbolizes who we are, what we are, and why we exist. His spirit of competition and determination serves as a beacon of goodwill from Minnesota to the world.”

In Capetown, South Africa, a competitor collided with his boat, but Mike repaired Duracell’s bow while continuing to race.

He made it around the world in 132 days 20 hours, bettering his previous time

by two days – and won a new U.S. record for solo circumnavigation.

In the next serialization:

Mike had emerged brilliantly as a new racing champion, but a new “toughest of

the tough” race beckoned: the Vendee Globe. For that, Mike needed a new

racer....an extreme racer that was built to do only one thing: win a race.

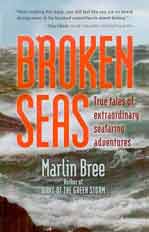

Excerpted from Marlin Bree's new book, Broken Seas: True Tales of Extraordinary

Seafaring Adventure (Marlor Press, 2005). Visit his web site at

www.marlinbree.com.

Continue The Vision

The Mike Plant Memorial Fund was established to provide a sailing experience for

inner city kids. Donations can be made to:

Mike Plant Memorial Fund

in care of the Wayzata Sailing Foundation

P.O. Box 768

Wayzata, MN 55391

Visit www.wayzatasailing.org/mikeplant for more information.