|

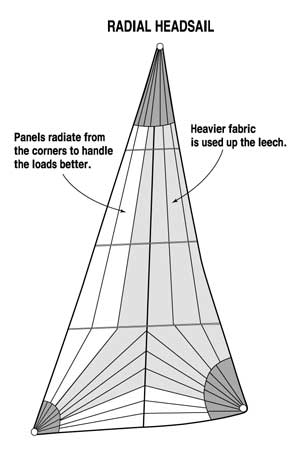

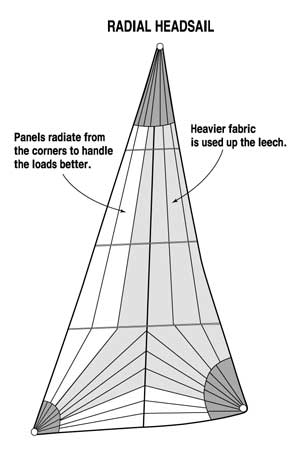

| Figure 4.10 Warp-oriented laminates were used to build radial sails, i.e., sails in which the panels were oriented along the load lines, not just stacked up parallel to the foot. |

Excerpt from Maximum Sail Power:

The Complete Guide to Sails, Sail

Technology and Performance

by Brian Hancock

(Nomad Press, $44.95). Copyright 2003.

All rights reserved.

A

PRIMER OF PANEL LAYOUTS

Part one of A Primer of Panel Layouts

began in the July 2004 issue of Northern

Breezes.

Radial Sails

While cross-cut sails were built from

woven Dacron, laminated fabrics allowed

sailmakers to build both cross-cut and

radial sails depending on how the fabric

was engineered. When the fabrics were

laminated the scrims were laid so that

the strength in the fabric could run in

the warp direction, the fill direction

or both. Fill-oriented laminates were

still used to build cross-cut sails,

while warp-oriented laminates were used

to build radial sails, i.e., sails in

which the panels were not just stacked

up parallel to the foot. (Figure 4.10)

Sailmakers had been building tri-radial

spinnakers for some time so the concept

of orienting the panels along the load

lines was not new. It was just that this

was the first time they could build

working sails with a tri-radial panel

configuration.

|

| Figure 4.10 Warp-oriented laminates were used to build radial sails, i.e., sails in which the panels were oriented along the load lines, not just stacked up parallel to the foot. |

One of the principal benefits of radial

sails is that the sail designer can

engineer sails with different fabrics in

different areas of the sail to address

specific loads. In other words, heavier

fabrics can be used along the leech of

the sail or at the head and clew where

loads are highest, while lighter fabrics

can be used in lower load areas like the

luff. These fabrics can differ in terms

of overall weight and specific lay-up.

They can also differ in terms of the

types of fibers and yarns used to carry

the load. For example, the sailmaker can

design the sail with low-stretch Kevlar

yarns in the high load areas and a

regular polyester in the rest of the

sail. In doing so, he can keep the cost

of the sail to a minimum while still

gaining the maximum benefit from the

exotic fibers. If the sail is going to

be used on a race course, the sailmaker

can add durable, chafe-resistant panels

through the foot area to take the abuse

handed out each time the boat tacked. If

the sail is going to be used for long

cruising passages similar patches can be

used in other high-chafe areas, for

example, where a mainsail rubs against

shrouds or spreaders. The same can be

done for woven cross-cut sails but the

patches are added on later.

Incorporating them in the original

design is a more efficient way to build

a sail.

Mainsails and Bi-Radial Sails

Of course, sails are used not only for

sailing upwind, but on reaches and runs

as well. Mainsails in particular have to

able to perform on every point of sail.

Some boats, like those that compete in

Olympic events, the America’s Cup or

other inshore events, spend most of

their time sailing either hard on the

wind, or sailing deep off the wind,

while others, like those that compete in

long-distance offshore events spend much

of their time reaching and running. Much

like headsails, when sailing hard on the

wind the principal loads on a mainsail

go directly from the mainsheet onto the

clew of the sail and then straight up

the leech. As soon as you bear away,

however, the loads are decreased and

extend further into the body of sail,

creating a whole new engineering

problem.

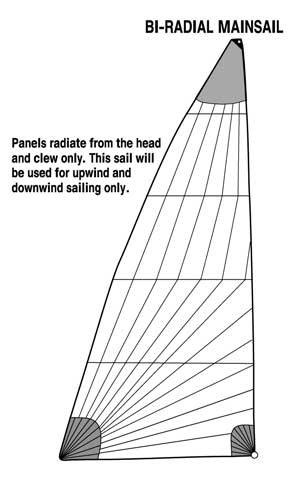

In the case of racing sails used on an

upwind/downwind course, for example, the

sailmaker may choose to build a

bi-radial main (Figure 4.11) with

load-bearing gores radiating out of the

head and clew only—bi-radial meaning

that there are only two sets of panels

radiating out from the corners, in this

case the head and clew. In this case,

although the body and tack of the sail

will be subjected to somewhat higher

loads on the downwind leg, as soon as

the racing sailor reaches the windward

mark and bears away, the loads on the

sail immediately decrease so that even

though the loads may be redistributed,

there will still not be any need for

tack gores.

|

| Figure 4.11 A bi-radial main with load-bearing gores radiating out of the head and clew only — bi-radial meaning that there are only two sets of panels radiating out from the corners. |

If, on the other hand the sail is being

designed for a passagemaker, the

sailmaker will want to deal with a

significant load on the tack since the

sail will be used for reaching and

running in all kinds of conditions.

Therefore strong tack gores are

necessary and the sail will be a

tri-radial construction. In the

beginning of this book it was made clear

that your sailmaker needs as much

information about your sailing plans as

you can give them. This is a perfect

example of how different sailing styles

can result in a need for different

sails.

Aligning fabric along load lines

Thanks to continuing research and

development, many racing sails are no

longer tri-radial in the true sense of

the word. Sail designers now have very

accurate load plots to work from and

it’s their job to make use of fabric in

the best possible way to accept those

loads. Loads are not linear and they do

not change direction uniformly and at

convenient places. In fact, not only do

they bend around a catenary, the curve

changes when the heading of the boat

changes relative to the wind. Many sail

designers now use panels that radiate

out from the corners of the sail and

then bend the panels within in the body

of the sail as best they can to match

the anticipated loads. In many ways, the

more bends in the fabric, the better the

sail, although building such sails is

quite labor intensive and the more

panels needed for construction, the

higher the cost of manufacturing the

sail. Again, it is a balancing act

between trying to make an effective sail

and keeping prices reasonable.

Asking Good Questions

The sailmaker’s choice of fabric styles

and weights are vast. How he uses them

to his best advantage is equally

infinite. The combinations are endless.

It always comes down to the single most

important part of the sailmaking

process: an understanding between the

sailmaker and customer. You need to be

clear about what kind of sail you have

in mind and how you plan to use it; you

also need to be sure to give that

information to the sailmaker even before

he works up a quote. Otherwise, it’s up

to him to guess, which is why sailors

often get different quotes from

different sailmakers who recommend

different sails and fabrics at vastly

different prices. It’s no wonder the

customers get confused if the sailmakers

themselves are working in the dark.

Below are some points to think about

when talking with your sailmaker about a

new sail.

|

• Do you plan to race or cruise?

• If both, what is the balance between

racing and cruising?

• What is your level of expertise?

• Do you really know how to trim sails?

• Is longevity more important than

performance?

• Is sail handling important or would

you sacrifice that for performance?

• Do class rules limit the number of

sails you can have on board?

• Are you planning on coastal cruising

or are you going transoceanic?

• If you are going offshore how many

people will be on board?

• Do you like to sail short-handed?

• Is stowage an issue on your boat?

• Will you be in an area where it’s easy

to get a sail repaired?

Armed with information and dozens of

fabrics to choose from, the sailmaker

can design and build you a custom sail

that meets your needs. It’s true that

two sails built from two different

fabrics with two different panel layouts

can do the job for you equally well;

sailmaking is an inexact science; there

is still plenty of room for art and

interpretation. But that doesn’t mean

that all sails will perform equally well

for your style of sailing.

A New Generation of Sailmaking

|

| Sails have become far more sophisticated than a simple tri-radial configuration. Here the panels change direction along the load lines in the sail. |

Of course, now that you have finally

figured out how the fibers and fabrics

are used to make sails, the sailmaking

world has taken another giant leap

forward leaving you behind once again.

The days of cross-cut and radial sails

are slipping into the past as new

sailmaking technologies find a foothold

in the industry and become more widely

accepted. Once the exclusive domain of

the racer, exotic construction

techniques like North’s 3DL, UK’s Tape

Drive, and Doyle’s D4 are becoming

mainstream. In fact, they are being

built and marketed to the weekend sailor

and offshore passagemaker as well as out

and out racers.

We will look at these technologies in

more detail in the next chapter, but

remember one thing. Newer or more

expensive is not always better,

especially in the case of sails. If

weight aloft is of no consideration to

you or your sailing plans, then you do

not need the latest high-modulus,

low-weight wonder fabric. In fact, if

durability and ease of onboard repair

are important, then you should

definitely think twice about buying that

fancy 3DL sail, since you might very

well be better off with a

high-performance Dacron. If, however,

performance is king, then it most

certainly makes sense to look at the

latest sailmaking technologies, decide

which one makes the most sense to you

and then go for it. An educated consumer

is in a powerful position. Know what you

want by knowing how you plan to use the

sails, and you will be satisfied with

the result.

Brian Hancock is an expert in sails,

sailmaking, and offshore ocean racing,

having made a career as a professional

sailor for almost three decades. He

apprenticed at Elvstrom Sails in South

Africa before leaving the country to

sail around the world. In 1981/82 he

sailed as a watch captain aboard the

American yacht, Alaska Eagle in the

27,000 Whitbread Round the World race.

Four years later he returned for a

second Whitbread, this time aboard the

British yacht, Drum. In 1989 he sailed

as Sailing Master aboard the Soviet

Union’s first, and by happenstance last,

Whitbread entry, Fazisi. With more than

200,000 miles of offshore sailing to his

credit Brian is uniquely qualified to

write about sails and the business of

making sails.

Brian also owned his own boat, Great

Circle an Open 50 carbon-fiber,

water-ballasted sailboat designed and

built for single-handed sailing and

Brian did a number of solo offshore

passages. Some of his experiences are

recounted in his book, The Risk in Being

Alive, published by Nomad Press. These

days he works on special sailing

projects and writes for magazines around

the world while raising a family in

Marblehead, Massachusetts.