Return to the Northwest Passage

by Roger B. Swanson

Sept 13: Good news in the morning. About 0800 the icebreaker helicopter pilot reported that, surprisingly, a lead had already started to form along the east shore of Franklin Strait. Underway at 0830, we headed out to join the icebreakers but found that ice had closed our escape route from Muskox Inlet. The icebreakers opened a path for us after which we started north with Louis S. Laurent leading the way followed by Sir Wilfred Laurier with Fine Tolerance in tow. Following astern came Cloud Nine, Jotun Arctic and Idlewild. We progressed well in 1 to 4/10 pack passing Camilla Cove and on into Bellot Strait which we found almost ice free. Yesterday it had been completely filled with pack ice.

|

| Crews of Idlewild, Jotun Arctic and Cloud Nine aboard Idlewild - snow was falling. |

When the icebreakers reached Magpie Rock at the east end of Bellot Strait they

warned us that the current was 7 or 8 knots running against us. Knowing this was

faster than we could motor, they suggested we might have to turn back to find an

anchorage until the tide turned. This was very bad news, and we were determined

to try to get through. We made it by working our way into the shallow water

north of Magpie Rock where the current was less. For a time we were only making

good one knot or less, but we hung on at full throttle, finally inching our way

past the rock where we started to make way again as the channel opened up. It

had been dark for several hours now, but we made our way into nearby Fort Ross

harbor anchoring at 2300. Relief! What a difference a day makes! Sir Wilfred

Laurier and Jotun Arctic also anchored at Fort Ross while Idlewild and Louis S.

Laurent continued on independently. We expressed our thanks to the icebreakers

and told them we would probably be underway in the morning. I cannot

overemphasize our respect and admiration for the seamanship and professionalism

exhibited by the master and crew of Sir Wilfred Laurier.

|

| September 13th - a lead finally opened and we headed north toward Bellot Strait. |

Sept 14: First light came at 0530 and we were soon underway. Jotun Arctic

planned to remain at Fort Ross for another day waiting for better weather and

Sir Wilfred Laurier was going to attempt to make the necessary repairs to Fine

Tolerance so she could also proceed independently. There was not a lot of ice in

Prince Regent Inlet, but enough that we had to be watchful at all times.

Headwinds increased significantly during the day and toward evening we

encountered more ice. With darkness coming on, strong headwinds, rain, and

scattered ice, we hove to keeping a close watch for growlers. Northeast winds

peaked at 40 knots making for a hard night.

Sept 15-17: Toward morning the weather eased a little and we tried it again in

20 knot northeast headwinds and rain. Although presently hindering our progress,

these two days of strong northeast winds were of particular interest to us. This

is the wind that we were waiting and hoping for during the entire time we were

trapped in Camilla Cove. Had it come a week earlier, it probably would have

cleared the ice around our anchorage, continued to open the lead already started

along the east shore of Franklin Strait, and cleared the way for us to

successfully transit the Northwest Passage! Coming now, it has probably cleared

Camilla Cove and very likely would have allowed us to escape without help. We

later learned that the Strait did open shortly after we left and remained open

long enough for us to have slipped through. Such are the fortunes of the Arctic.

Crossing Prince Regent Inlet on a port tack, we picked up a slight favorable

current along the east side. Later in the day we learned by VHF that Sir Wilfred

Laurier was able to make the needed repairs to the propeller of Fine Tolerance.

Both she and Jotun Arctic would soon be underway headed for Greenland. The

weather improved later in the day and the sun came out which was a welcome

change. With improved weather we elected to remain underway at night running at

reduced speed keeping a careful watch for ice.

Good progress was made the next two days with decreasing wind and seas as we

continued north and then east over the top of the Brodeur Peninsula. The water

was now relatively ice free which was a big relief. The good weather gave us a

chance to transfer some of our deck stored fuel into the main tank. Our route

continued east and then south down Navy Board Inlet bringing us to the village

of Pond Inlet on the north coast of Baffin Island on Friday evening, September

17th.

|

| Rugged snow covered south coast of Bylot Island as we left Pont Inlet. |

At Pond Inlet we fueled, showered and had dinner ashore, which was a nice treat.

For the rest of the trip we were short one watch stander because Judd had to

leave to fly back to California. As a result of joining Cloud Nine, he was six

weeks overdue at home following his Mars research project. Pond Inlet has a

population of about 2000, primarily Inuit, and is one of the principal

settlements in the eastern Arctic. Unfortunately we did not have much time to

look around because we were all anxious to move on.

Reports of new ice starting to form in parts of the eastern Arctic kept us

conscious of the fact that we needed to hurry along. On Monday morning we

completed provisioning as quickly as possible and were underway at 1230. Thirty

five knot easterly winds were forecast for the channel between Baffin Island and

Bylot Island and we were anxious to get out ahead of the bad weather. This was

the beginning of a 1500 mile passage southeast to St. Anthony, Newfoundland. We

were looking forward to reaching a world without ice!

The weather was still calm as we started east in Bylot channel admiring the

remarkably beautiful snow covered mountains that rose precipitously on both

sides of the channel. All of Bylot Island has been set aside as a national park.

As we cleared the eastern end of the channel we started to see icebergs, but not

a high concentration of them. The predicted winds arrived, but in the open water

outside the channel, they did not exceed 20 to 25 knots. Nevertheless, 25 knots

on the nose makes for heaving going, especially in the cold of the Arctic. We

had frequent snow and sleet showers that would sting our faces as we peered

forward scrutinizing the water ahead for ice.

|

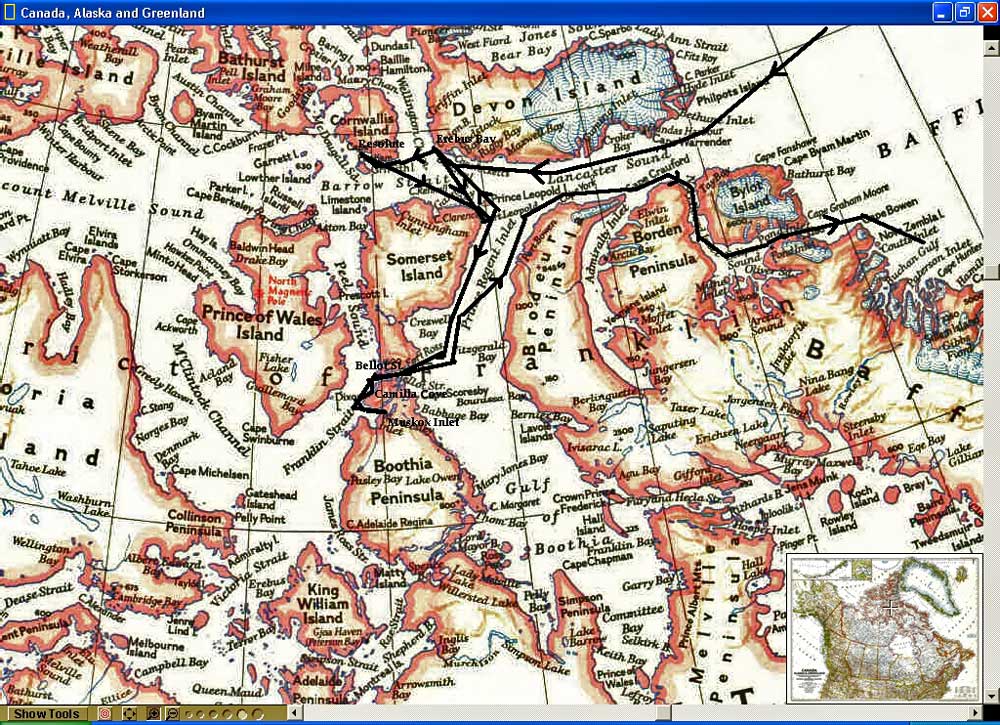

| Here is a map of the challenging route Cloud Nine took. |

The headwinds stayed with us for several days as we worked south encountering

only scattered ice. But now that we were past the equinox, the nights were long

and a careful watch was needed after dark. The large icebergs showed up pretty

well on radar, but there was always the risk of growlers. We continued to run at

night, but at reduced speed, usually about 3 to 4 knots depending on visibility.

One gigantic iceberg probably rising 150 feet or more above the water line,

obviously from Greenland, was a stunning sight. Most of the icebergs we saw were

smaller, probably originating in the eastern Canadian Arctic. As the days passed

conditions improved with occasional sunshine, but we still experienced snow

showers every day. A pod of orcas brightened one afternoon.

On September 23rd we crossed the Arctic Circle again officially leaving the

Arctic region after nearly 12 weeks north of the circle. However, the cold

continued to follow us. We were now 400 miles from Pond Inlet running downwind

part of the time in 10 to 15 knot winds making good progress. We took advantage

of the settled weather to once again transfer fuel from the drums in the cockpit

to the main tank. On September 24th our radar died which was a major concern

since it was our primary iceberg warning at night. Fortunately we were seeing

very few of them but the night running was stressful.

A few days later the wind changed and we had 30 knots on the nose again. By this

time the snow showers had turned to rain. It was interesting how everyone’s

spirits seemed to droop when the weather was tough, probably a result of

everyone being tired and anxious to get home. Being short one watch stander, we

stood four hours on and six off making the watches come around pretty often,

especially if it happened to be your cook day. Two days later the weather

improved and everyone felt better again.

On September 28th weather forecasts predicted gale winds from the south, not

good news for us. St. Anthony was only 100 miles away, but we could not make it

during daylight hours and I was not anxious to try a night entry without radar.

When the gale warnings changed to storm warnings, we decided it was time to look

for a place to hide.

The early morning hours of September 29th found us making our way toward a small

cove called Cartridge Bight just north of the Strait of Belle Isle that looked

like it might provide shelter. We anchored just after daybreak and settled in

before the strong southerly winds arrived. Cartridge Bight turned out to be a

good choice. The wind picked up during the day and blew hard all night peaking

at 60 knots, but our anchor held and we rode comfortably. It blew all the next

day, but dropped rapidly in the late afternoon and we were underway again

shortly before midnight.

The 60 mile passage from Cartridge Bight across the Strait of Belle Isle to St.

Anthony went well. Arriving at 0730, we proceeded directly to the same dock

where Cloud Nine fueled last June and requested fuel to be delivered by truck as

soon as possible. Gaynelle took off for the grocery store and we started taking

on water. By 1100, fuel, water, and provisions were on board and we were

underway. This crew was in a hurry!

|

| Leaving Canadian waters - we took down our weather beaten courtesy flag. |

It was necessary to backtrack 20 miles north until we could head west through

the Strait of Belle Isle. The weather was beautiful with sunshine, a rare

commodity in this part of the world. It turned blustery in the Strait overnight,

but then improved and we made good progress moving south along the west coast of

Newfoundland. Cabot Strait started peaceful enough, but by the time it finished

with us we had furled our main and were beating to windward again against strong

winds and rain under staysail and mizzen alone.

Eventually the wind eased and the next three days were spent working our way

against moderate southwesterlies along the south shore of Cape Breton Island and

Nova Scotia, most of the time in heavy pea soup fog. This was difficult with our

radar inoperative but we didn’t have any choice. We were not happy with our

headwinds, but glad to be far enough south to avoid the succession of strong

gales passing north of us.

Our route took us down the channel between Nantucket Shoals and Georges Bank.

Out GPS was invaluable navigating between the banks in fog. When passing through

this area, one cannot help but develop an increased respect for the old timers

who navigated these waters with their treacherous shoals and swift currents in

the fog with little but a lead line and dead reckoning to help them find their

way.

Later in the day we cleared the shoals and were able to set a course for our

final destination, Norfolk, now only 400 miles away. As we approached the coast

we had the wind behind us helping us along for a change. The entire east coast

the the United States was being pounded by a series of low pressure systems and

torrential rains that flooded many areas including parts of Norfolk. We shared

some of this rain with them but on October 12th, Cloud Nine and her crew found

their way through Norfolk’s busy harbor complex and once again moored at the

Norfolk Yacht Club.

We were a tired but happy crew. Our time in the Arctic had both humbled and

exhilarated us. But now, our trip was over. As time goes on, our venture into

this unbelievably beautiful but unforgiving wilderness of the Arctic will mean

something different to each of us, but will remain one of the unforgettable

experiences of our lifetimes.

Of course we were disappointed to not complete the Northwest Passage. There were

less than 50 miles separating the southbound tracks of Cloud Nine and Jotun

Arctic and the northbound tracks of Idlewild and Fine Tolerance when we were

stopped by the closing ice pack. Another day’s progress and we probably all

would have made it, but in the Arctic, the weather and the ice have a final

word.

This has been the last excerpt from Roger Swanson’s book Into the Ice.

Roger Swanson is from Dunnell, Minnesota. He has cruised Antarctica twice,

almost the Northwest Passage and circumnavigated four times. He has received

numerous international awards for cruising and seamanship.