|

Excerpt from Maximum Sail Power:

The Complete Guide to Sails, Sail Technology and

Performance

by Brian Hancock

(Nomad Press, $44.95). Copyright 2003. All rights reserved.

A STITCH IN TIME

|

Sail Care and Repair

A book that claims in its subtitle to be a comprehensive guide to everything

about sails, is nothing about sails unless there is a chapter on how to repair

them. Ultimately, a compromised sail inventory is not only bad for performance;

it can affect the safety of both the boat and crew. Knowing how to care for your

sails and repair them while you are at sea is a fundamental part of good

seamanship. In fact, it's up there with knowing how to deploy and use storm

sails. If you find yourself on a lee shore without an adequate inventory you

might rue the day you turned down a lesson on basic sail repair. Note that while

your local sailmaker will know how to do fancy repairs that blend into the rest

of the sail, this chapter is more about how to effect a rudimentary repair while

under way and how to take care of your sails on an ongoing basis. First let's

look at basic sail care.

Sail Care

A number of factors contribute to sail wear and tear including excessive

flogging and prolonged exposure to sunlight. The delicate yarns used in

high-tech racing sails are especially vulnerable to these two forms of

degradation. Other forms of wear and tear are all too familiar to many cruising

sailors. Chafe, for example, is a big factor as is using the sail out of its

engineered wind range. Finally, there is the issue of moisture and mildew.

Flogging

Modern fibers are very sensitive to being bent, and over time even the best

sails will find a natural hinge around which to bend, which sooner or later will

become a weak spot in the sail as the yarns break down and disintegrate. Letting

sails flog is the principal contributor to this bending, and while it's

impossible to prevent a sail from flogging on occasion, you should be aware of

this problem and keep the flogging to a minimum. For example, when setting a

mainsail many boat owners motor into the wind at speed while the sail flaps

crazily back and forth, whereas it's only necessary to have sufficient speed to

keep the bow pointed into the wind. By doing so, you can minimize flogging.

Walking on sails has a similar effect to flogging. Many sailors think nothing of

stepping or sitting on bags of Kevlar sails, but the constant creasing

ultimately damages the fabric. If possible, roll the sail when it's not being

used and stow it out of the way. While it's natural to attempt to fold a

headsail on its original crease, avoid doing so. The crease will only form a

weak spot in the sail.

Sunlight

The other ingredient to a good day on the water (other than wind that causes

flogging) is sunshine. Unfortunately, as stated earlier, many fibers are

extremely UV sensitive and lose much of their strength from constant exposure to

sunlight. All fabrics will eventually break down, some quicker than others, so

making an attempt to keep sails covered when they are not being used will pay

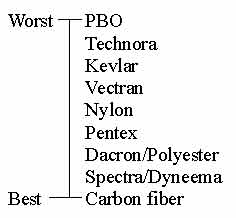

dividends down the road. In Chapter 2 we learned about fibers and the degree to

which they are able to resist UV degradation. The following list, ranked from

worst to best in their ability to resist UV degradation, are the fibers

mentioned in Chapter 2:

Fortunately for cruisers, other than carbon (which is of no use because of its

brittle nature) the fabrics most commonly used for cruising sails - Spectra,

Dacron, Pentex, and nylon - are ranked relatively high. That's not to say you

shouldn't take care of the sails. Indeed if you plan to spend a lot of time in

the Tropics then you really need to take extra care when it comes to protecting

your sails from the highly damaging effects of ultraviolet rays. This means

keeping the sail cover on the main when it is not in use, and the headsails in

their bags. Also consider adding strips of UV material to the leech and foot of

your roller-furling sails if you have not already done so. You should remember,

however, that even these covers lose their ability to protect the sail from the

sun. Boom covers and sunshields get threadbare over time and as the fabric ages

the sun will be able to penetrate through to the sail. For real bullet-proof

protection you might consider having a mainsail cover built that has a foil

liner on the inside. The foil liner is the same material that is used for making

space blankets and it completely blocks the sun's harmful rays. An investment in

a bullet-proof cover and UV-prohibiting films and adhesives when the sails are

new will also help extend the life of the sail.

|

| On a rig like the one on Drum, chafe patches were a must. In addition to having the patches someone was sent aloft daily to check for chafe and other kinds of wear and tear. |

Chafe

This is something that occurs on all sailboats, although it's passagemakers and

long-distance racers who are most sensitive to the problem because their sails

are subject to long hours of continual use. Fortunately, you can do quite a bit

about it. Racing sailors, for example, can install spreader patches to take the

abrasion off the fabric as it is dragged over the spreader ends each time you

tack. They can also install stanchion patches to compensate for the sail rubbing

up against these pieces of hardware. Cruisers can not only take the same

precautions, but take the process even further since they are usually less

concerned about weight. For example, an additional chafe strip can be sewn along

the foot of the sail where it clears the lifeline, and seams that rub against

the mast and rigging each time you tack can be covered with a layer of

sticky-back Dacron to protect them. Full-batten mainsails are particularly

vulnerable to chafe where the hard surface of the batten comes into contact with

the rigging or lazy jacks, so if you are planning on sailing downwind for a long

period of time and the batten will be rubbing up against the rigging, have your

sailmaker sew a length of webbing on either side of the batten pocket.

There is also a lot you can do on the boat and rigging itself to help minimize

chafe. Take some time to go over the boat carefully in search of snags. Cover

exposed cotter pins with tape and silicon, and where you can, cover rigging with

leather. Cover the spreader ends with leather or tape them with sticky-back

Dacron so that there are no sharp points to snag the sail. This extra effort

will really help your sails last longer.

Using a Sail Beyond Its Designed Wind Range

When sailmakers engineer a sail they realize there are times when a sailor is

going to be caught carrying too much canvas, so with this in mind they build in

a significant margin of error. As a result, don't panic if you find yourself in

a situation where the sails are overloaded, since it's likely that the sails,

especially if they are new, will be able to withstand the extra load. This does

not mean, however, that you can fly your sails in any conditions with impunity.

Sailcloth has a certain yield from which it will recover, but continually

pushing the sail to or beyond its yield point will only lead to problems,

especially with sail shape. If you measure the life of a sail by how long it has

a decent shape, rather than by how long it's a triangular piece of fabric, then

you need to be sensitive to a sail's yield point and sail your boat accordingly.

Moisture and Mildew

It's inevitable that sails on a sailboat are going to get wet, so if you want

your investment to last longer it's important for you to make an attempt to dry

the sails when you are finished with them. A long-distance cruising sailor may

laugh at the idea, and with fair reason. But racing sailors, weekend cruisers,

and daysailers do have an opportunity at day's end to dry and stow their sails

properly, and they should always be sure to do so.

If the sails are made from woven Dacron, for example, the salt particles in salt

water will work their way into the fine yarns of the fabric. Later, when the

water evaporates, they will become tiny salt crystals with razor-sharp edges.

These sharp edges chafe at the fine fibers, snapping them one by one and slowly

breaking down the fabric. The resin coating on new Dacron fabrics makes it

difficult for the salt to penetrate, but over time this resin will break down

allowing the diluted salt crystals to penetrate. Your best bet is to rinse the

sails with fresh water and let them dry in a warm shady place.

Laminated sails, especially those with the film on the outside, are not as

susceptible to salt as their Dacron counterparts, but it is still a good idea to

rinse them off after they have been used since some fabrics are more prone to

mildew than others. Bear in mind that usually it's not the fabric itself that

attracts mildew, but rather the dirt and oils that collect on the surface of the

sail. If you see a mildew spot it's best to treat it right away with a squirt

from a cleaner like Tilex, which can be found on the shelves of most

supermarkets.

Nylon is especially vulnerable to dampness, since when it is wet it loses as

much as 15 to 20 percent of its strength. If you stash your spinnaker away still

wet and then attempt to set it the next day in a stiff breeze, be careful. The

sudden shock loading that occurs when the sail fills could cause it to explode.

Your best bet is to wash your spinnakers with fresh water and then dry them on

the lawn before using them again.

Another reason for washing sails to rid them of salt is the fact that salt eats

away at hardware (like leechline cleats or blocks) mounted on the sail.

Therefore, cleaning and drying your sails will not only prolong the longevity of

the fabrics, but also that of the other pieces of equipment that are essential

to making them work as well.

Sail Repair

As is so often the case in sailing, preparation is key, and carrying good sail

repair equipment on board will allow you to fix most damaged sails. A sewing

machine is nice, but not essential, and your decision about carrying one on

board will be determined by the area where you are sailing and the types of

repairs you want to be able to do. Basically there are two ways to approach each

repair - a quick fix to help you make it to the next port, or a more elaborate

job as good as any done by a sailmaker in a sail loft. If you are cruising

remote islands, the chances of finding a sailmaker will be equally remote, and

you should take a sewing machine on board and learn how to use it. If you are

hopping up the East Coast of the United States, leave the machine behind and

learn how to do quick patches so that you can make the next harbor safely since

this region has lofts aplenty. Either way there are some basic techniques you

should learn.

First, no matter what the job, you will need to do a quick damage assessment, a

job that requires a flat wooden surface, sharp scissors, and a helping hand. If

the rip is in a high-load area of the sail, you will fix it differently than if

it is in a low-load area. The edges, for example, especially the leech and foot

of the sail, will need quick and careful attention, while a rip in the middle of

the sail can be slapped closed with a piece of sticky-back Dacron and left that

way until you have time to do a proper job. For example, I once sailed over 300

miles with a hole in the middle of my spinnaker. It snagged on a shackle as I

was hoisting it, but the rip was far from any load area, and there was no danger

of the hole enlarging. I had run out of sail repair material so that's the way

it stayed. If the rip had been near the luff or the corners, I would have been

forced to drop the sail and not use it.

| Repairing downwind sails Do a damage assessment. Clean the torn area with fresh water or alcohol. Lay the sail on a smooth surface and piece the edges together. Trim the frayed edges. Patch with sticky Dacron (temporary) or nylon strips (permanent). Remove the temporary patch if doing a permanent patch. Repairing working sails Do a damage assessment. Clean the torn area with fresh water or alcohol. Lay the sail on a smooth surface and piece the edges together. Trim the frayed edges. Patch with sticky Dacron building up the layer to the required strength. Sew the patch to the sail (especially if in high-load area). |

Sticky-Back Dacron

This simple product is one of the most important pieces of equipment on any

boat, especially one heading offshore. Sticky-back Dacron is simply Dacron tape

with an adhesive backing and is to the sailmaker what duct tape is to a boat

builder: an indispensable item. It comes in various weights, but the three-ounce

Dacron is the most versatile and also seems to have the best adhesion. You can

build up to a required weight by layering the Dacron, doing so in a gradual

transition so you will not end up with a "hard spot" at the edge of the patch

that acts like a hinge and later becomes a weak spot in the sail. Before adding

any sticky-back, make sure that the area to be patched is clean and dry. Wipe it

clean with fresh water or better still with alcohol (not your best gin, but an

industrial type). It is important that there is no grime or grease on the sail.

Sticky-back will adhere to damp Dacron, but the bond will be much better if the

sail is clean and dry, and better still if you are able to heat the sail once

patched. Use a hair dryer or leave the sail in direct sunlight. The heat softens

the adhesive and it bonds better. Use sticky-back for repairing all Dacron sails

and for a quick fix on spinnakers, although it's not a good idea as a long-term

repair on the latter since the Dacron is not compatible with nylon and will form

a hard spot in the sail that could end up ripping after some time. You can use

ripstop nylon tape for repairing spinnakers, although it does not have the

adhesion of sticky-back Dacron and usually needs to be sewn down. Ripstop nylon

tape is the same as sticky-back Dacron except that it's made from nylon fabric

rather than Dacron.

You can also use sticky-back Dacron for repairing laminated and molded sails. In

fact, it's especially effective when the outer layers of the fabric are film

since it adheres extremely well. In general, with lighter fabrics sticky-back is

probably best left unsewn since the needle holes only serve to weaken the base

fabric.

Patching

The key to good sail patching is to lay the repaired area out flat and piece the

edges together where you would want them to be when the sail is repaired. Use

the underside of one of your wooden floorboards for a level surface and secure

the fabric using your awls and pins. Trim off any frayed edges and pulled

threads to allow the fabric to lay flat. Cut strips of sticky Dacron wide enough

to cover the gap and carefully place them over the torn area. It's important to

have the repair come out as smooth as possible since a hard spot will be a weak

spot in the sail. Work from the center of the sail out toward the edges so that

if your repair does not match up exactly, you can trim the excess fabric. If you

work in toward the middle of the sail and find that there is excess you will

have a problem. You can't simply cut off a chunk of fabric from the body of the

sail.

On a Dacron sail decide how many layers of sticky-back you will need to build up

to the sail fabric weight and layer them over your initial patch making each

successive patch larger than the one before. Remember that the sticky-back

weighs 3 ounces so divide the fabric weight by three to see how many layers you

need. It's okay to go an ounce or two over, but don't overdo the patch. Again,

you want to avoid a hard spot in the sail that could present a problem down the

road. A 12-ounce patch on a 7-ounce sail is a problem waiting to happen.

Patch both sides of the sail. If you are repairing a rip in the middle of the

sail and you are able to clean and dry the sail before patching it, you will not

need to sew the patch. Simply lay an extra-large patch over the area and allow

the adhesive to hold it all together "in sheer." As you near the leech, foot, or

corners of the sail you will need to sew the patch since these are areas that

experience higher loads. When doing so you might want to lay a piece of regular

Dacron under the sticky to add strength to the repair, using the sticky to hold

it in place. For a simple patch use a straight stitch - basically an

up-and-under stitch that runs in a straight line - keeping each stitch no longer

than a half-inch long and sewing both sides of each row of stitches. Sew in one

direction first and then sew back in the other direction using the same holes

until each stitch has thread either side of it. If you are sewing through an

area of heavy material, first bang holes in the fabric with a hammer and awl

before sewing, then snap the sharp end off your needle and sand it to a blunt

point. It will follow the awl hole with its blunt point and not try to make a

new one of its own.

When using sticky-back Dacron for a quick repair on a nylon sail, apply

extra-wide patches near the leeches and sew the leech tape back on with a sewing

machine or by hand. Because the sail is too big for the small area on board,

sketch the repair and come up with a plan before starting, once again working

from the center of the sail out toward the edges. If you are planning on doing a

proper repair, follow the same procedure for a temporary repair, and then turn

the sail over and patch it properly with strips of nylon the same weight as the

spinnaker. Cut the nylon and lay double-stick tape down the edges. Change the

direction of the patch at each seam to match the thread direction of the fabric.

Your temporary repair will hold the sail together allowing you to patch with

nylon. Remove the backing on the double-stick tape, lay the fabric down smoothly

and then sew the patches with your sewing machine. Once the nylon patches are

sewn down, turn the sail over and cut away the temporary sticky-back Dacron

patch with scissors. Cut along the edge of the stitching on the permanent patch,

and remove the fabric and sticky-Dacron. Finally sew a row of stitching down the

seam and across the new patch to hold it all together and aid the transition of

the patch into the sail.

If a corner ring pulls out, you can replace it with one of your spare rings.

Eyeball where the ring should be positioned, and lay strips of 2-inch nylon

webbing through the rings and onto the sail. Use double-stick tape to hold the

webbing in place, stagger the ends of the webbing so that their transition into

the sail is gradual and then secure the entire repair together with a layer of

sticky Dacron since it will be easier to sew the webbing if everything is held

in securely in place. Follow the same procedure of banging holes in the webbing

with an awl and then sewing it with blunt needles. Put in a few rows of zigzag

stitch, being careful to pull each stitch as tight as you can.

If you run out of sticky-back Dacron and double-stick tape, spray adhesives work

quite well to hold the fabric in place. So does a glue gun, although you will

have to sew the patches down since the spray glue and hot glue do not have a

strong enough bond.

There is nothing difficult about repairing your own sails. Like most everything

in sailing, a little common sense goes a long way. Good preparation, a little

patience, and a good sail repair kit are all that you need. Here then is what a

good sail repair kit will contain.

Sail Repair Kit

Your onboard sail repair kit will be as comprehensive and varied as the passage

you are planning and should be tailored to suit your needs. Store the bulk of

the items in a bag in a dry, convenient place, and have a smaller bag containing

items that you need more often in a more accessible place. The smaller bag

should include:

scissors

wax thread

needles

whipping twine

some sticky-back Dacron

Keep the needles in a tight container wrapped in a cloth that has been lightly

soaked in sewing machine oil. Also wrap your scissors in an oiled cloth, since

even though they are stainless steel they will rust if not protected. Roll the

pieces of nylon, sticky-back Dacron and regular Dacron tightly, and hang them in

a waterproof chart storage tube from the overhead in your forepeak.

A basic sail repair kit will include the following items. Amounts will vary

depending on the size of your boat and the trip you are planning. The amounts

noted here would be suitable for a 40-foot yacht planning a transatlantic

passage.

1 pair stainless steel scissors

1 pair regular scissors as backup

1 knife dedicated to sail repair

6 awls to secure the sail while patching

2 dozen push-pins with plastic heads to secure the sail while patching

1 adjustable hand palm for hand sewing sails

3 seam rippers

1 roll of pre-waxed hand sewing thread

1 roll of sticky-back Dacron tape 5 inches wide

10 feet of sticky-back Dacron 54 inches wide

5 rolls of double-stick tape

2 cans of spray adhesive

3/4-inch tubular nylon webbing

2-inch nylon webbing

2 stainless steel rings with bar

10 feet of Velcro

a selection of needles, size No.14 and 15

staple gun and staples

lump of wax

assorted pieces of Dacron and nylon

A more comprehensive kit would also include:

a spare set of battens

spare hanks

a spare luff tape the length of your longest headsail

leechline cord twice the length of your mast height

an entire corner patch of one of your spinnakers

hot knife

Nicropress tool and sleeves

Hole cutter and assorted rings

20 feet of seizing wire

|

Sail Repair at Sea My second Whitbread Race was aboard Drum,

the British yacht owned and sailed by Simon le Bon, the lead singer of the

rock group "Duran Duran." The sails on Drum were huge. It was in the days

when the Whitbread was raced under the old IOR rule, and we raced with more

than 20 bags of sails on board. The headsails were masthead and made from

Kevlar. They were massive and very difficult to repair. We had to lash them

as tightly as we could and hammer the fabric through the sewing machine in

order to carry out even the smallest repair. The spinnakers were 5,000

square feet, and when they blew out they came down to me, the sailmaker, in

a dozen bits of wet nylon. I had a 4-by-4-foot piece of upturned floorboard

as my repair loft. To repair the spinnakers I had to first dry the torn

edges with a hair dryer. Then I trimmed the frayed bits before trying to

figure out where each piece went. Fortunately I was good at jigsaw puzzles

and always managed to get the sail back together. |

Determine the Condition of Your Sails

The end of the sailing season is a natural time for you to take stock of your

sail inventory and go over each sail to evaluate its condition. You can ask your

sailmaker to do the checking, but it's not rocket science and you can save

yourself some money if you do it yourself. All you need is a dry lawn and some

time on your hands. This might also be a good time to give the sails a final

rinse in fresh water before stowing them for the season.

Check Fabric

It's fairly easy to gauge the integrity of your fabric, especially a woven

Dacron. Take a blunt edge like the back of a knife and rub the surface of the

sail. If it comes up shiny and smooth where you rubbed then you know that the

fabric is still in reasonably good shape. If, on the other hand, the fibers

start to get fuzzy then you know that there has been some UV degradation and you

need to be concerned. In some cases you might be able to rub a hole in the

fabric in which case the sail will have to be replaced. If your sail has ripped

during the season, take note of how it ripped because it will give you some

clues as to the condition of the fabric. Smaller yarns degrade and break quicker

than the larger yarns and in most cross-cut sails the small yarns are found in

the warp, especially if the fabric is fill-orientated. If the sail developed a

rip parallel to the leech, in other words across the warp, then you can be sure

that some degradation has occurred to the smaller warp yarns. The same amount of

degradation will have occurred to the fill yarns, only it will take longer for

it to show.

Check Seams

Seams are the most vulnerable areas of sails and a thorough check of each one

may save you a costly blow-out down the road. If your sailmaker used colored

thread it will make your job a lot easier. If not, examine each seam for loose

or broken stitches, and mark each place with a piece of colored sticky Dacron.

Hold the sail up to the light and determine whether you can see daylight through

the stitch holes. If you can, it's a sign of impending trouble, since it means

the seams have been overloaded and are vulnerable to blowing apart. Pay

particular attention to the areas around the corner reinforcement patches. If

the last row of stitches show sunlight through the stitch holes, it may mean

that the corner patches are not large enough or strong enough for the sail, or

that you have overloaded the sail on more than one occasion. Have your sailmaker

either re-sew the seam or possibly extend the reinforcement patch.

Check Hardware

It's important to take a close look at the sail attachment hardware like batten

cars, luff slides, and hanks to see if there is any wear and tear or hairline

cracks. The cars on the inboard ends of battens are often under a compression

load, while the intermediate slides are under tension. Look for wear, paying

particular attention to the slides at the head of the sail and above each reef,

since these are the ones most heavily loaded. Check the webbing and stitching

that hold the hardware to the sail to be sure that it is still strong.

Hanks generally do not fail, but it's worth checking each piston if it's a

piston-hank, or spring if it's a Wichard-type hank to see if it works properly.

Sometimes a halyard gets in behind the piston or spring and bends it so that it

does not close easily, or worse yet, it does not close at all. If there are hank

reinforcement patches on the sail check them for chafe; if not, check the sail

to see if there has been some noticeable point loading on the fabric.

Also take a close look at the leechline cleats and other hardware that is bolted

to the sail. If the sail has been put away wet, these small aluminium pieces are

the first to feel the effects of corrosion.

Look for Chafe

It's important to check the sail over for chafe even if you have chafe

protection spreader patches or the like. By the end of a season the light Dacron

chafe protection could have worn through and will need to be replaced. Batten

pockets are always vulnerable to chafe and should receive extra attention. The

same applies to the edges of the sail like the bolt rope along the luff of a

mainsail or the foot of a genoa where it passes over the lifelines. Make notes

and mark the sail with a piece of colored sticky Dacron where it needs

attention.

Replace UV Protection

The sunshield on cruising headsails is good for a number of years depending on

where you sail, but it's not good for life and so you should replace them every

few years. This is especially true if you live and sail in the Tropics. Remember

that the acrylic fabric is being exposed to the blazing sun all day every day

whether or not the sail is being used.

Maintaining Your Investment

Sails are a big investment, not only in terms of hard-earned money, but also in

time and energy. It's important that they be taken care of and thoroughly

examined on a regular basis. There is nothing quite so disheartening as a sail

blowing out, and blown sails are almost 100-percent avoidable. These days with

modern materials, sophisticated computer programs for determining loads, and

judicious engineering, a sail should never blow out unless some other factor has

come into play. Chafed seams or a small rip caused by a sharp edge usually form

a weak spot in the sail. It's important to overall seamanship to take care of

your sails, so be kind and cautious and you should never have a problem with

ripped sails.

Brian Hancock is an expert in sails,

sailmaking, and offshore ocean racing,

having made a career as a professional

sailor for almost three decades. He

apprenticed at Elvstrom Sails in South

Africa before leaving the country to

sail around the world. In 1981/82 he

sailed as a watch captain aboard the

American yacht, Alaska Eagle in the

27,000 Whitbread Round the World race.

Four years later he returned for a

second Whitbread, this time aboard the

British yacht, Drum. In 1989 he sailed

as Sailing Master aboard the Soviet

Unions first, and by happenstance last,

Whitbread entry, Fazisi. With more than

200,000 miles of offshore sailing to his

credit Brian is uniquely qualified to

write about sails and the business of

making sails.

Brian also owned his own boat, Great Circle an Open 50 carbon-fiber, water-ballasted sailboat designed and built for single-handed sailing and Brian did a number of solo offshore passages. Some of his experiences are recounted in his book, The Risk in Being Alive, published by Nomad Press. These days he works on special sailing projects and writes for magazines around the world while raising a family in Marblehead, Massachusetts.