The Big “D” Is for Derecho

A storm system to beware of

By Marlin Bree

If sailors on Lake Superior or other northern lakes sometimes

feel that the breezes are a little stiff during early thunderstorm gusts, they

might like to know that their gut feelings were correct:

Can you say, "derecho?"

|

Author on foredeck of boat

In his 20-foot wood/epoxy sloop, Persistence, author Marlin Bree sailed

through a rare, progressive derecho on July 4, 1999, that also became the

"storm of the century" in the BWCAW blowdown. Bree's experience on Lake

Superior in the 100-mph. downbursts is included in the NOAA's "About

Derechos" pages on its web site. |

A derecho is a superstorm that can come up over the horizon

without much warning. There'll be the usual dark clouds that'll sweep toward you

with remarkable speed, and, unlike many storms that you can take in your stride,

this one will be different, as you will quickly find out. If you are lucky, you

may get a few minutes' severe weather warning on your boat's VHF, but don't

mistake it for another squall that will be over in a few minutes.

The first winds to hit you will make their strength felt on your mast, and, your

boat will heel alarmingly, and, if you are so unfortunate as to still have sails

up, your main probably will have a chance of either being stretched badly or

even ripped. Winds are often initially in the 60 to 80 mph range, which is an

insane amount of wind to expect a small sailboat to stand up to.

But there's worse: Out of the clouds will come downbursts of cold, heavy winds

that will be at even greater speed than the straight-line winds. Thus is a

derecho (pronounced Day - Ray -Cho) and it is a Spanish word meaning, straight

ahead, as opposed to tornados, which means turning.

However you pronounce it, the Big D derecho is a nasty business - nature's

apocalypse -- as I came to know from first-hand experience. I am one of the few

boaters ever to have been caught in a progressive derecho, one of the worst

kinds that are now in the record books, and, I managed not only to sail through

one, but also to write record its effects on my small sloop on Lake Superior. In

fact, "my derecho" is detailed in the new NOAA web pages, "About derechos,"

which tells of my boating experience as well as others caught in the decade's

worst derechos.

I learned about the NOAA site when I first heard from Bob Johns, a veteran of

NOAA's Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Oklahoma, who had a special interest

in the superstorms called derechos and did several studies about them. He

invited me to take an advance look at the test site, "About derechos," before

NOAA published it officially in July. The web site is found at

www.spc.noaa.gov/misc/AbtDerechos. Developed by Johns and fellow forecaster

Jeff Evans, the web pages define derechos, tell what causes the superstorms,

gives strength and variation of winds, and, presents some information on

historic derechos. It includes satellite and radar images.

|

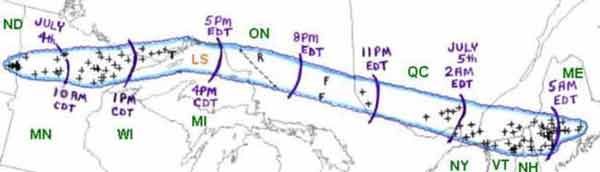

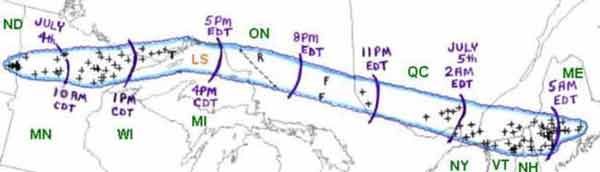

1999 July 4 Derecho chart

from NOAA site:

The July 4, 1999 derecho was a huge superstorm that lasted farther and

longer than many news reports have indicated. Beginning on the western

border of Minnesota, the storm accelerated to become a derecho in the

proximity of the BWCAW and northern Lake Superior. It did not end in the

BWCAW but instead blasted eastward in a path of destruction for several days

all the way to Maine. |

For boaters, it can be fascinating viewing, but you can surmise through the

pages that although forecasting is improving, it's still not easy to identify a

derecho until it has formed. That means a derecho can pose a particular danger

to boaters. As I already found out, a derecho can move so quickly that its fast

winds can catch a boater off guard. A derecho has severe wind gusts greater than

57 mph., and, straight-line winds that can travel long distances at 60 to 80

mph., but that's not the worst.

Embodied in a derecho is a family of downburst clusters. The derecho is a "worst

first" storm, with the strongest winds coming during the opening minutes of the

storm, with a sustained series of downbursts can blast the surface below with

cold, heavy air. Downbursts can have speeds of more than 100 mph., and, over

open water, speed up. Unlike many common thunderstorms, which can be over in an

hour, a derecho can last for ten hours or more as it moves through various

areas.

• Derechos are a unique danger to boaters because the

superstorms can't be predicted in advance, and, they can arise quickly

with little or no warning. Boaters may not be able to get to a place of

shelter, and, they can be caught out with their boats unprepared for a

superstorm. The worst form of derechos, the progressive derecho, often

occurs most during prime boating months.

• The chief danger is not the derecho's straight-line winds, which can be

in the severe wind range, but its many downburst clusters with intense

winds of more than 100 mph. that rush downward and bowl over anything in

their path

• Derechos last for long periods of time, and, cover huge areas.

• Preceding a derecho, the atmosphere may appear dead or still, followed

by a quick rising storm pushed along by 60 to 80 mph winds. Onrushing dark

clouds may be confused with a thunderstorm, or, a tornado.

• Despite advances in meteorology over the last decade, derechos are still

somewhat of a scientific mystery. |

An example of one is found in NOAA's Historic Derecho Events, which gives

information on significant derecho events causing severe damage and casualties

in the last several decades. Among them are Independence Day Derecho Events,

and, here you can click on the July 4-5, 1999, "The Boundary Waters - Canadian

Derecho," which lasted far longer than news reports indicated and which caused

huge damage not only in Minnesota's BWCA but also all the way east into Maine, a

track of destruction of about 1,500 miles. This was the derecho I encountered

while sailing my 20-foot ultra-lightweight centerboard sloop, Persistence, solo

out of Grand Portage, MN., to Thompson Island, located at the mouth of Thunder

Bay, and I was overtaken by high winds that set my sailboat on its beam ends,

out of control. I was especially fascinated on the NOAA site to click on the

Duluth NWS forecast office as well as the American Museum of Natural History

links to see radar images of that very derecho forming. With winds estimated in

excess of 100 mph., this extraordinary derecho tore down huge amounts of trees

in the BWCA, injured 70 people and killed two persons before it ultimately ended

in Maine.

In the BWCA storm, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) on its

EarthBulletin Storm Tracking web pages had an interesting comment that as the

storm passed to their north, meteorologists in Duluth saw the wind signature

diminish on the screen. Meteorologists could view a bow-echo reflection of

raindrops, so they still had a rough idea that the gust front was located,

though they could not longer determine actual speeds at ground level. "It was

precisely the moment when (the storm) evolved into a full-blow derecho," AMNH

reported. It added, "As fate would have it, however, Duluth was the last radar

station along the path to northern Minnesota - and the last radar to see the

storm before it turned into a derecho."

During that onrushing storm, little advance warning was given boaters, including

myself. I heard a Canadian VHF warning only minutes before the derecho swept

onto Superior. The Thunder Bay Coast Guard had issued a Mayday for a sailboat

that had overturned, with three persons in the water. Part of the difficulty was

that the storm had knocked out electricity as it hit the Ontario city, and, one

fireman I talked to reported having about the ten minutes warning, "Something

big is coming through." They saw a blackness rolling across the Sawtooth

Mountains, and, watched the sky turn green. In the fire tower, the rain was

blowing so hard it shot through the top door's seals, with water pouring down

steps "like somebody was up there with a fire hose."

Though the July 4, 1999 "Green Storm" tore up 477,000 acres in the BWCAW, in

what was one of the largest North American forest disturbances in recorded

history with its wind gusts "in excess of 100 mph.," that derecho was not the

strongest to come through the northern area. On July 4, 1977, a derecho that

pounded across northern Wisconsin had measured speeds of 115 mph., and another

one, on May 31, 1998, a derecho with wind gusts at 128 mph and gusts estimated

at 130 mph., hit Lower Michigan.

Though the derecho has only begun to be understood and recognized - as well as

remaining difficult to forecast until it has actually formed - it probably

should be in the lexicon of most boaters. It is a rare, but not infrequent

storm, sometimes preceded by only minutes of advance warning of heavy weather on

the VHF, or identified visually by heavy, black clouds quickly rising on the

horizon, with a distinct lowering. Boaters should be aware that a derecho is a

large, dangerous storm, and skippers should be wary, exercise caution, put heavy

weather sailing techniques into practice, and not be lulled into a false sense

of security or caught off guard.

Marlin Bree (web site: www.marlinbree.com)

contributed to NOAA's "About Derechos" web site and his nonfiction book, Wake of

the Green Storm: A Survivor's Tale, tells of his and other boater's adventures

during the July 4, 1999 "Green Storm" record progressive derecho that devastated

the BWCA and surrounding areas.