| Little

Things Loom Big During an Emergency

by Tom Rau

Posted

July 17, 2005 On Watch: Muskegon, Lake

Michigan, July 1, 2005. A beachside resident called

Coast Guard Station Muskegon on Friday afternoon

reporting a sailboat floundering off the beach

north of Muskegon Harbor. Jay Mieras, the reporting

source, reported that a woman on the sailboat

was waving her hands in the air. Posted

July 17, 2005 On Watch: Muskegon, Lake

Michigan, July 1, 2005. A beachside resident called

Coast Guard Station Muskegon on Friday afternoon

reporting a sailboat floundering off the beach

north of Muskegon Harbor. Jay Mieras, the reporting

source, reported that a woman on the sailboat

was waving her hands in the air.

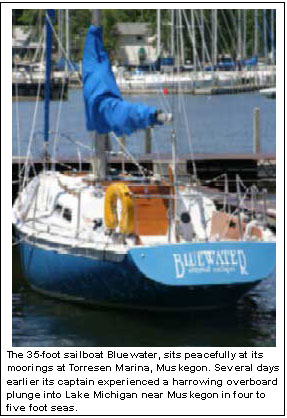

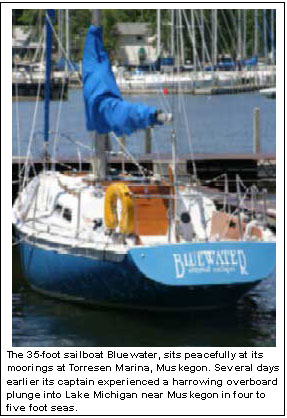

The

35-foot sailboat Bluewater, sits peacefully at

its moorings at Torresen Marina, Muskegon. Several

days earlier its captain experienced a harrowing

overboard plunge into Lake Michigan near Muskegon

in four to five foot seas.

Within

minutes, the Station Muskegon’s 30-foot

rescue boat broke the pier head at Muskegon Harbor.

Four to five foot seas driven by 20 knot winds

greeted the Coast Guard crew as they pounded north

towards the sailboat’s reported position.

“When we approached

the sailboat, I noticed a horseshoe flotation

device trailing off the stern attached to a tether

line,” said Mike Tapp, Executive Officer,

Station Muskegon. He added: “This was not

good, you had that feeling that someone had gone

overboard.”

Chief Beatty, coxswain

aboard the 30-foot rescue boat approached the

sailboat. “A female was hollering that her

husband had fallen overboard but she didn’t

know where,” said Chief Beatty.

Chief Beatty conducted several

quick shoreline searches of the area that yielded

negative sightings. The situation was not good:

a person in the water and sailboat being quickly

driven towards shore, and its sole operator unable

to control the craft.

Now what? Do you look for the

husband or do you save the woman and the sailboat.

Fortunately the situation resolved itself. A “Good

Sam” Jim Homan, 61, had spotted the floundering

craft from shore and he and a buddy grabbed a

two-person kayak and reached the sailboat just

as the Coast Guard finished its second search

of the shoreline.

Being an experienced sailor,

Homan took control of the sailboat allowing the

Coast Guard crew to continue the search

But where?

Locating a man in seas glazed

over by white wind whipped spray did not look

promising for the poor soul in the water. Tapp

discovered from Homan that the sailboat carried

a hand-held GPS. Homan passed the GPS to Tapp.

Chief Beatty commenced searching while Tapp worked

the handheld device. After two minutes of punching

keys and being bounced about he tapped into the

track line the sailboat had followed. “I

could see where the straight track line ran askew.”

Tapp figured that is where the man went overboard

as his wife began tacking to recover him. Tapp

placed a cursor marker where the track line ended

and bingo the GPS offer the latitude and longitude

of where the man had gone overboard.

Chief

Beatty passed the coordinates to a Coast Guard

helicopter aircrew who had joined the search.

Within minutes, the aircrew spotted the man in

the water, wearing a bright international-orange

life jacket. Meanwhile Chief Beatty had transferred

Tapp and Seaman Benjamin Cuddeback over to a Muskegon

Sheriff’s boat that had picked up the man

along with a Good Sam. Tapp said, “The man

was shivering uncontrollably. His lips were blue.”

Tapp and Seaman Cuddeback removed

his wet clothing and applied their own body warmth

by direct body-to-body contact with the man as

the sheriff boat raced to the Coast Guard moorings

and an awaiting ambulance.

Boat Smart Brief: Richard Coan,

age 67, was released the following afternoon from

Muskegon’s Hackley Hospital. His core body

temperature when admitted was 86 degrees. There

is no doubt that the life jacket saved his life.

He had been in the 61 degree water for nearly

two hours. He later told me the reason he wore

the life jacket is because his wife, Robin, insisted

on it. God bless her.

He told me he had moved forward

on the deck to adjust the main sail and the boom

swung over and bumped him backwards and over the

handrails. His wife started the engine, but its

gears wouldn’t engage. Mr. Coan said that

when he departed White Lake Harbor, a turnbuckle

device on the gear linkage had fallen off and

thus he couldn’t engage the gears.

Mrs. Coan made several attempts

to recover her husband, but the sailboat drifted

away. She had tossed over the horseshoe life ring

but failed to untie it from the boat. She couldn’t

luff the main sail to take out the wind because

it would require leaving the tiller and going

forward to the foot of the mast to release the

sail. It’s the same reason she didn’t

call for help over the marine radio, again fearful

of leaving the tiller and placing the 35-foot,

six-ton Erickson sailboat broadside to the wind

and a possible knockdown. In dire straights, she

sailed for shore hoping to attract attention,

which she did.

Mr. Coan admitted it was the

little things that nailed them: when the gear

linkage device fell off he should’ve returned

to White Lake and repaired it in calm water. He

had recently switched the boom sheets on the main

from control from the tiller to the foot of the

main, which required leaving the tiller to luff

the main sail. “Had I thought this through,

I would not have changed the boom sheets,”

said Mr. Coan.

As for the life jacket, I advised

him to purchase a signal mirror and whistle, a

day and night flare, and a strobe light. Twice

the helicopter had passed nearby but failed to

see him in the wind swept sea. Mr. Coan admits

that it’s the little things that loomed

big when the unexpected visited. Thanks to a life

jacket the little things didn’t add up to

the final tally.

|

A

Related Concern

In another matter that relates indirectly

to the above case, the Coast Guard along

the eastern shore of Lake Michigan has experienced

a rash of unmanned boats adrift. During

one case, the Coast Guard spent seven hours

tracking down the owner. Coast Guard officials

urge boaters to place permanent I.D. markings

on these small watercraft and secure them

to a fixed object. How does this relate

indirectly to the life-saving case? Coast

Guard resources could’ve been elsewhere

tracking down an adrift derelict and not

immediately available when time was of the

essence searching for Mr. Coan. As stated:

it’s the little things.

In

recognition to Rescue Responders during

this life-saving rescue:

CG304445 Crew (initial response for PIW)

BMC Michael Beatty

BM1 Michael Tapp

BM1 Scott Lenz

BM3 Salvador Nunez

SN Benjamin Cuddeback

**(BM1 Tapp & SN Cuddeback later transferred

to MC-872 and assisted Mr. Coan as a team)

Muskegon County Boat 872 (first county boat

O/S)

Officer Dave Vanderlaan

Muskegon County Boat 875 (second County

Boat O/S)

Officer Raymond Lundeen

Officer Dan Stout Jr.

CG304445 Crew (second sortie to escort sailing

vsl with Mrs. Coan and Mr. Homan)

BMC Michael Beatty

BM1 Scott Lenz

BM3 Salvador Nunez

EM3 Chance Rupe

SN Christopher Rickett

Crewmembers I recommend for inclusion: They

made ready CG49412 and CG234393 to assist

if needed and stood by the unit. They also

acted as line handlers and or helped transfer

the PIW from the County boat to shore.

BM1 William Hosford

MK1 Robin Yoder

BM2 Brian Fiscus

EM3 Chance Rupe: Mbr. recalled off liberty

MK3 Zachary Michaud: Mbr. recalled off liberty

The crew of CG Rescue 6508

The Group Grand Haven Comms Watch. |

Tom Rau is a long-time Coast Guard rescue responder

and syndicated boating safety columnist.

Look for his book, Boat Smart

Chronicles, a shocking expose on recreational

boating — reads like a great ship’s

log spanning over two decades. It’s available

to order at: www.boatsmart.net,

www.seaworthy.com,

www.amazon.com, or through local bookstores.

TOP

|

Posted

July 17, 2005 On Watch: Muskegon, Lake

Michigan, July 1, 2005. A beachside resident called

Coast Guard Station Muskegon on Friday afternoon

reporting a sailboat floundering off the beach

north of Muskegon Harbor. Jay Mieras, the reporting

source, reported that a woman on the sailboat

was waving her hands in the air.

Posted

July 17, 2005 On Watch: Muskegon, Lake

Michigan, July 1, 2005. A beachside resident called

Coast Guard Station Muskegon on Friday afternoon

reporting a sailboat floundering off the beach

north of Muskegon Harbor. Jay Mieras, the reporting

source, reported that a woman on the sailboat

was waving her hands in the air.