Keeping Outboards Running, Maybe

Forever

by Marlin Bree

A veteran sailor’s look at the myth and the reality of the much maligned

two-cycle outboard engine, from Superior to the North Atlantic

The storm had come up without warning and now my twenty-foot ultralight sloop was out of control. In the wild winds, the bow dug in and Persistence went into a semi-pitchpole and lay on her side, not getting back up. Behind me, I heard my small outboard come out of the water and racket unmercifully. It was a sound that I feared.

I was soloing my way into the wilderness archipelago of islands in northern Lake

Superior on the Canadian side. If my 5 hp two-cycle outboard gave out here, I

would be in deep trouble. Maybe in more ways than one.

|

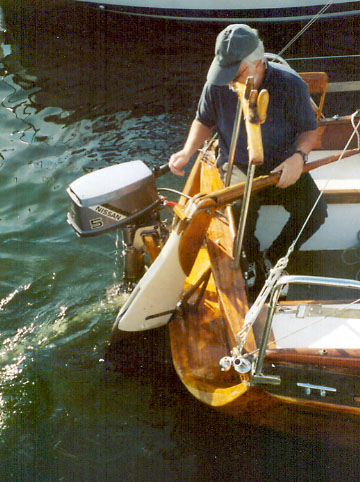

| Marlin Bree on his Nissan Outboard. |

I tried to grab the throttle, but another wild downburst came along. The

engine roared out of control and there was little help for it. The mast,

which now was at about a 45-degree angle to the water, went back down again,

mast spreaders almost touching-and scary. The rudder blade was also out of

the water.

I had the surprising sailor’s luck to be caught in the July 4, 1999,

progressive derecho - the Green Storm - that swept over Minnesota’s BWCA,

snapping old-growth pines like matchsticks in about a half a million acres -

the worst blowdown in recorded North American history. One weatherman, Paul

Douglas, said the derecho produced downbursts up to 130 mph.

When the downburst-the first of many-passed, the 20-foot boat plopped down

again with a splash of water. The spinning prop caught water and I finally

made my way into the refuge of the small harbor inside Thompson Island.

It had been a hell of a test of an outboard. It had been revved wildly, had

been out of the water for minutes at a time, and didn’t have cooling water

to prevent it from overheating. Or the impeller to bust.

The next day, I tried the engine again - more than a little worried. Despite

the abuse, the engine started right up, ran without a hiccup, and, despite

being out of the water for minutes at a time at full throttle rpm, did not

overheat. It still seemed to have its impeller intact, despite the dire

factory warnings of not to operate the engine out of the water. It ran

beautifully as I continued my month’s long voyage into the wilderness area.

That engine is still with me these many years. Yes, it’s a looked down-upon,

somewhat maligned and totally unfashionable two cycle, and, yes, it has had

some minor problems in its latter years, but I am not about to change my

engine to a four cycle until this thing gives up. That may be a long time

from now. Maybe forever.

I am aware of the advances in technology taking place in outboard engines

for good old boats. A few years back, I helped built a river skiff for the

Saint Paul Science Museum, at its old quarters and in a place overlooking

some dinosaur bones. When we put the boat in the Mississippi River, I had to

bend over to listen to hear the engine running. That was because it was a

one of the newest 4 cycle Hondas of about 40 horsepower and it ran so

quietly it hardly even seemed to tick. I liked the “green” concept - it

emitted less hydrocarbons and stuff. It got better gas mileage. I was

impressed.

|

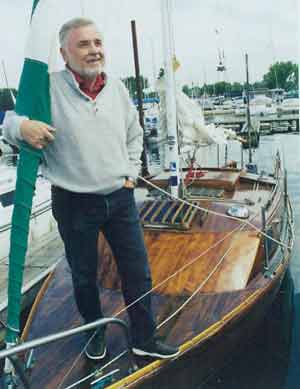

| Author at helm of his sailboat Persistence motoring into the slip. |

I was not so enthusiastic as I looked at prices and weights at a new, small

four strokes for my own sailboat. My own engine kept running fine, even

after the storm escape, and, frankly, I was not ready to plunk out the $1500

or so for an equivalent sized four stroke. Nor did I want the added weight

on the transom. My engine’s 43 pounds was a handy weight to take off and put

on the transom. But the four strokes got into the 50 and 60 pound sizes that

took a lot more heft to handle. A lot more.

I don’t want to say I won’t someday get a four stroke or a new fuel injected two

stroke, but I do look upon my two-stroke experiences and those of others with

some balance and respect.

I’m for good old outboards for good old boats. To my mind, these engines

really are strokes of genius.

Two cycle engines dominated the boating world since Ole Evinrude invented

the first practical outboard engine in 1909. For their size, they have

considerably more horsepower than a four cycle, along with more torque, and,

a quicker buildup of power, which comes on at lower rpms. They have fewer

parts than a four cycle, and, they cost less to build, buy and maintain. I

don’t know quite how to measure this, but I think the two cycles are a lot

tougher, too.

The disadvantages are the ring-ding noise of the two cycle as well as the

unburned fuel and oil that goes up in blue smoke - the environmental pollution

blues has gotten the manufacture of old style two cycles banned in the U.S.

But the old two cycles-rugged workhorses of the marine environment-have done

more than boaters ever thought they could. For example, I have a friend who

crossed the treacherous North Atlantic with one. It was really just an old

fishing motor.

Gerry Spiess, formerly of White Bear Lake, Minnesota, took his elderly 4

horsepower Evinrude out of Virginia Beach, Virginia, into the Atlantic on a

bracket hanging off the transom of his Yankee Girl. But he soon ran into

a treacherous storm and at times, he told me, his engine got hit so hard with

waves “I thought it had been torn off.” After the Atlantic tamed down, he pulled

a little maintenance: he changed the spark plug. Then off he went under his

trusty old two stroke. When the winds came up, he ran with sails, but when he

neared England, he used his two cycle again. He arrived to a cheering crowd in

Falmouth, England, his two-cycle purring along. Yankee Girl had set a record for

the smallest sailboat-only ten foot LOA-to cross the North Atlantic, from west

to east.

In my book, the small two-cycle outboard also should have had some sort of

trophy or record. It had crossed 3,800 miles of a tough ocean and it had given

no problems, either in starting or in running, despite heavy waves and rough

weather. It was not a new outboard either: Gerry had used it for years on other

boats and in testing Yankee Girl on Minnesota’s White Bear Lake.

|

| Author on foredeck of his sailboat Persistence. |

A couple of years later, he sailed Yankee Girl to attempt to cross

the Pacific Ocean, a voyage of almost 8,000 miles. He again chose a two

cycle: a new 4-½ horsepower Evinrude, but that almost ended in disaster.

After a storm at sea, he could not start the outboard - and he was hundreds

of miles from land. Countless breakers had beaten the engine and he’d heard

it shudder and bang behind him on the transom. More than once, he wondered

if it’d been torn off. But after the storm, he became becalmed, and, with

great confidence (“these engines always fire up,” he recalled in the book,

Broken Seas) he pulled the starting cord to get the gas up. But nothing

happened. After hours of attempting to start the engine, including changing

plugs and checking the fuel supply, he traced the problem to the throttle

arm. Peering beneath, he saw that the engine had a shut-off or kill switch

at the end of the throttle arm. If you pushed the button, the engine stopped

-what had happened was that the seawater had shorted out the kill switch.

With needle-nose pliers, he snipped the wires, bypassing the switch and

pulled the starter chord hard. With a whuff of smoke, the little two-stroke

started up and soon settled into a raspy idle.

Interestingly enough, the meticulous Spiess, who felt he had to master every

detail of his home-built boat and everything aboard, had overlooked

something. “You never want to go to sea in a new boat,” he often told me.

But he had gone to sea with a new and untested outboard.

Once he fixed the kill switch problem, he and the outboard got along

famously. In the doldrums on his way to Hawaii (his first port of call and

the longest single leg of his voyage), he ran his engine just barely turning

over at a fast idle, which was a stately cruising speed of around 2.2 knots

(2.53 mph.), which he maintained almost nonstop day and night for the next

six days. He’d even refuel while underway by unscrewing the filler top of

his inside six-gallon main gas tank and pour in gas from one of the gas cans

from the bilge. He did stop the engine a couple of times to change spark

plugs-cheap insurance, he figured. He stopped the engine by choking it off,

since the kill switch was dismantled.

The engine was a key to his record crossing and he used it when he could not

sail under his twin-jib setup (his preferred way of travel when he had wind - it

was much faster). He had done the math on his two cycle: at fast idle, a gallon

of pre-mixed gas and oil would last seven hours. A 24-hour run would take only

3.5 gallons. He carried 54 gallons of pre-mix in the bilges, down low for

ballast.

Amusingly enough, before he set off on his voyage from Long Beach,

California, he sometimes was looked down upon by power boaters with the big

yachts with hundreds and even thousands of horsepower that favor the Pacific

coast. “How far can you cruise?” he often joked with the yachters; they’d

answer maybe 200 to 300 mile range.

Then Gerry did the math: With her two cycle outboard engine, Yankee Girl

had nearly a thousand mile range. She carried 54 gallons of pre-mix and

could power at fast idle 17 statute miles per gallon. That would give him a

whopping range of about 918 miles.

The 4.5 horsepower two cycle could push Yankee Girl faster than her

usual fast-idle cruising speed of 2.5 miles per hour. But speed was not part

of his plan: Spiess did not want to go fast, only far. And when he pulled

into Sydney, Australia, harbor to a hero’s welcome, he and his trusty two

cycle had set another record: crossing the world’s largest ocean in the

smallest boat.

Spiess’s records could not have been possible without his trusty two cycle

“fishing motor” outboards. In his voyages, he demonstrated how reliable and

tough these engines could be. Even as many boaters lust after the shiny new

four strokes, the remaining old gas-oil premix two cycles (new ones are not

being marketed in the U.S. any more) are gaining some new boating friends.

At least they’re being appreciated somewhat better.

A while back, when one veteran boater heard at his local marine store about

the upcoming ban on two cycles, his answer was to buy two of them, so the

story goes. He figured they’d last him the rest of his boating life.

But maybe he should have heard about the guy by the name of Max E. Wawrzniak II.

Max really likes two cycles and may even be one of the older engines biggest

fans. He has no less than 150 outboards, all two cycles. He allowed he did have

one four cycle, but he got rid of it.

Max is a pleasure boater, not a professional mechanic, who works only on his

own engines and maybe those of a few other friends. He describes himself as

entirely self-taught and swears he’s never had any formal outboard repair

training. He also has written a delightful new book, Cheap Outboards: The

Beginner’s Guide to Making an Old Motor Run Forever.

“An old outboard motor (and I do mean old; maybe as old as 50 years),” Max

writes, “may provide you with a reliable power source for your boat for

considerably less money than a new outboard or even a used late model one.” He

swears there are a good many two-cycles lurking about hardly used and unloved

that can be fixed up inexpensively by most anyone and can run “till doomsday.”

I like that kind of thinking, even though Max is mostly interested in

mid-50s to early 70’s Johnson’s and Evinrudes. He likes these engines

because they “are just about the simplest engines ever built and performing

minor repairs.requires only a modest collection of tools and a minor

knowledge of mechanics.” He notes, “You probably already own most of the

tools you will need.”

He observes that many boaters “would rather own a shiny, new 4 cycle outboard

motor than a greasy, dented old one, all things being equal. But all is not

equal and that shiny, new outboard will cost a chunk of change.”

Heh. Heh. In Cheap Outboards, Max goes on to do some math: Considering that even

a small new four-cycle can cost you upwards of $1,500, he argues you can pick up

an old two cycle in fairly decent mechanical condition “but not real pretty” for

no more than $150 and probably not more than $100, if you look in the right

places. He argues many old outboards are lightly used and often hidden away and

simply forgotten.

Maybe their owners traded for a fashionable new four cycle. Or the two cycle

started having some problems. I know something about the latter: after going

through several stormy voyages on Lake Superior and years of general use, my

5 hp two cycle Nissan started cutting out at any speed other than idle and

fast idle.

This was by now at least a 12-year-old outboard that had been used pretty hard.

I had maintained the engine entirely myself, snapping in a new plug each season,

draining and replacing the lower case oil, and, running the engine dry of gas

before I put it away for the season by storing it inside my basement.

I had purchased it for a Superior trip after I bonged up my other two cycle: a

long shaft 5 hp two-cycle Mariner, which had caught its tip in an unexpected

hole in a Cornucopia, Wisconsin, launching ramp. With horror I still remember my

wife, Loris, yelling to me: “Your outboards in the water.” It had broken its

collar and I could not get it repaired right away in the area. A friend of mine

Joe Boland, in his 35-foot catamaran, Tullamore Dew, generously decided to loan

me his new dinghy engine: a Mercury 5 horsepower two cycle. I screwed it tight

on my transom bracket, straight out of its packing carton. It fired up right

away and ran beautifully. I came to learn that Tohatsu made this as well as my

Nissan two cycle engine.

But now my Nissan wasn’t running right and I quickly learned why. “About 90

percent of all two cycles that come into my shop,” said Greg, my small

engine guru, “are carb problems.” His fix was to run some gunk and varnish

remover through the carb, and, that worked fine. I also had him replace the

water impeller, since the Nissan maintenance manual, which I finally had

gotten around to reading again, said the rubber-type impeller should be

replaced every two years. After it had been changed after about 12 years, I

looked at the original: it looked fine to me, and the mechanic said it

looked good to him, though the new impeller provided a slightly better “pee”

or discharge.

But what about the old “dunked” two cycle Mariner? After I pulled it out of

Superior’s icy waters, I dried it carefully, pulled the spark plug and shot in

some oil. Then I shoved it into one corner of my garage, lying on its side,

figuring I’d do something about it sooner or later. About seven years later, I

got the broken metal collar replaced with a used one. I clamped the engine in a

bucket of water, connected a running hose to keep up the water level, and

snapped on the engine’s old fuel supply-dating back to when the outboard got

dunked. I pumped up the bulb, choked the engine, then pulled it through a few

times. Within two hard pulls, it whuffed into action and ran just fine. I

decided to use it as a backup engine on Superior.

These days, I try to take better care of my two cycles. I keep my Nissan on

its swing bracket on Persistence’s transom covered with a Sunbrella

cloth cover I fashioned myself. This cloth covering keeps the sun’s heat off

a bit and helps to keep the gas from cooking off in the carb during hot

days. I always begin each season with fresh, new gas and keep only a small

supply in my auxiliary gas tank. I dump some carb cleaner in the gas supply

- usually Seafoam. I run lean 100-to-one synthetic oil mix in the gas, and,

I use synthetic oil in the lower gears. I snap in a new sparkplug at the

beginning of the season. And, most important, I run the gas out of the

engine on the boat (I unsnap the fuel-line connector to the engine and let

the outboard run out of gas) before I haul Persistence at the end of the

season. I bring the engine indoors into my basement for storage, upright, in

a warm place.

From time to time, I give it a pat. I owe my life to that little engine, but

even so I couldn’t help but wonder if it was not the time to think about a

shiny new four stroke or contemplate eventually getting one of the

anticipated small-bore oil injected two strokes. I mentioned this to my

outboard guru, Greg, who cut me off sharply: “If you had one of those during

the storm, you wouldn’t have made it back.”

That sharpened up my thinking. Maybe I was fortunate to have a simple, reliable

two stroke-especially when I needed it. Makes one think, doesn’t it?

Marlin Bree (www.marlinbree.com) is the author of numerous boating books,

including Wake of the Green Storm: A Survivor’s Tale, and Broken Seas: True

Tales of Extraordinary Seafaring Adventures.

All contents are copyright (c) 2006 by

Northern Breezes, Inc. All information contained within is deemed reliable

but carries no guarantees. Reproduction of any part or whole of this

publication in any form by mechanical or electronic means, including

information retrieval is prohibited except by consent of the publisher.