TWO FISTED DOCKING

by Marlin Bree

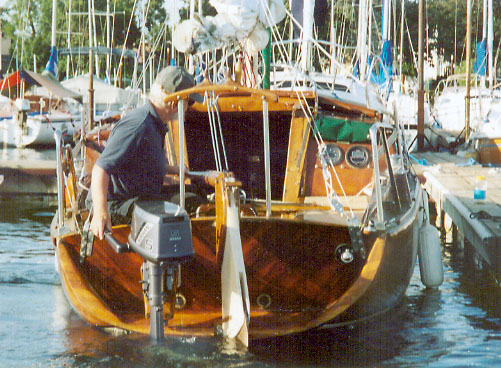

Author at helm of

Persistence.

The NorSea 27 next to me in the Bayfield, WI, marina berth was

getting ready to shove off into the Apostle Islands, but the skipper and crew

were concerned about a strong crosswind that swept down over the hills, kicking

up little waves. They had rigged lines off the stern and bow to haul the

keelboat around in the fairway.

"We've been having trouble getting her around - she won't back up in these

crosswinds," they yelled to me.

Onboard my 20-foot Persistence, I was also headed into the Apostle Islands for

several weeks and the crosswinds worried me, too. I was leaving first, so for

insurance, I took a line off my bow, which the helpful NorSea crew wrapped

around a piling.

I started the engine on my ultra lightweight centerboard sloop - a chip on the

wind if ever there was one, and, almost guaranteed to drift sideways in a breeze

- and I put over the helm to port. Just as important, I cocked my 5-horsepower

outboard the same direction.

With a little throttle, we were off, climbing stern first into the starboard

crosswind. At the peak of the turn, with my bow pointed downwind, I snikked the

Nissan into forward, and, we motored ahead - perfectly placed.

I waved.

In amazement, the keelboat crew tossed me my line. "You don't need this," they

said as I motored away.

I never found out how the NorSea made it out from its slip, or why the crew was

having a problem with that particular boat, but I do know that docking - getting

to and from a dock or slip - is one of the big concerns of most skippers,

including myself.

It's not so much a problem of getting out on a fair day, but the problem of

getting a sailboat out of slip that looks far too short increases in

worrysomeness as the wind pipes up. It gets even more of a concern as you have

to dock the boat under heavy weather conditions.

A recent internet poll which asked skippers how comfortable they were when they

docked their boats reported that only a little over 10 percent of all skippers

said that they did all their dockings perfectly, without any problems, in all

conditions. About a fourth of skippers said that they still have problem,

especially in cross winds, and, over 50 percent said that they do OK unless

conditions are poor, in which case they are in trouble. About ten percent said

they usually had trouble, were constantly concerned, and, frankly could use a

little help.

Single versus twin screws: I have seen an expert skipper fit a catamaran within

inches on either side in a gusty condition at a tiny Lake Superior dock. That

was Capt. Thom Burns, at the helm of Joe Boland's Tulamore Dew, as we sailed the

Shipwreck Coast to the Soo Locks.

But most sailboats are not equipped with the ultra-maneuverability of that big

cat's twin rudders and twin diesels that can spin a boat around almost within

its own length.

Most have single rudders, and most have single outboard power plants - and it's

my guess that small sailboat rig represents the vast majority of sail boaters in

the Northern Breezes sailing area.

Two Fisted Approach: From my observations in a variety of ports over the years,

I've seen that most sailors when they dock simply steer with their rudders only,

not taking advantage of the great maneuverability of their outboards.

An outboard can be steered as well as the rudder. It can help carve a turn into

the wind, or, help get a bow around in a crosswind landing. It's such a natural

process that the sailors who use both the rudder and the outboard wonder why

everyone doesn't use this process that I call Two Fisted Docking.

An outboard can be steered as well as the rudder. It can help carve a turn into

the wind, or, help get a bow around in a crosswind landing. It's such a natural

process that the sailors who use both the rudder and the outboard wonder why

everyone doesn't use this process that I call Two Fisted Docking.

Onboard Persistence, I have my rudder and my outboard mounted so that both fall

readily to hand. My 5-hp. two-cycle Nissan outboard engine is mounted directly

outside my portside stern area, since I am right handed. I steer with my right

hand when I am seated on the portside.

The outboard controls lie readily within reach from my seating position - as

opposed to reaching over the tiller to an engine mounted on the other side of

the transom.

Coordination: Here's how it works: I put my left hand on the tiller, and, my

right on the outboard's throttle arm. Naturally, the collar tensioning screw is

loosened so that the engine pivots freely. Surprisingly enough, it doesn't take

a lot of effort to control a good outboard.

I try to practice coordinating both the rudder and the outboard so they are

pivoting at the same time, and, with very little effort or practice, that

coordination falls readily to hand. I've seen mechanically inclined sailors

report on a mechanical link between outboard and tiller, but that's really not

necessary. In some cases, it's more of a problem than simply learning how to use

both at once - the approach I advocate in Two-Fisted Docking.

Two-fisted departures: Let's get ready to shove off. I let the engine warm up

for a minute or two as I get my boat ready and dock lines off. The last thing I

want is for the engine to be cold and stall just as I'm entering the fairway,

especially on a windy day.

With the warmed-up engine on idle, I snick it into reverse gear and cock both

the rudder and the engine in the direction I want to turn. I give the engine a

little gas, but not a lot, and we get underway easily and smartly, adjusting the

gas to fit the situation. A racing engine is not a good idea, nor is too much

speed. A controlled, but steady approach is what you want. You want to get water

moving past your keel and your rudder, so that you've got some bite from both -

essential to control.

With the boat moving well, but out of the slip, I will feel the crosswind on the

bow, trying to knock us off course. Remember that you are in a dynamic, fluid

element. Your boat will slip and slide around. That's not only part of the

challenge, it's part of the fun.

If the gusts come from the starboard forward quarter, and I am exiting to port,

the wind will catch Persistence's ultra lightweight bow, giving us a shove to

port - the direction we don't really want to go. I have a 105 percent genoa on a

Cruising Design roller furler, and, that creates wind age. Persistence is also

very skitterish under these wind conditions since she draws very little and is

an ultra-lightweight craft.

To keep an easy arc, we might twist the throttle a bit, and increase the angle

of the outboard and the rudder. If there's a lot of wind blowing, I might just

get in closer to the opposite row of boats to let them shoulder the wind, rather

than attempting to make the completion of my turn in mid-channel.

Usually, you have room to set the boat up within several boat lengths of leaving

the slip, even if you have to let a few more go by to get yourself properly

aligned with the fairway. You will have some momentum going on the bow, and, you

should execute your turn with a little angle into the bow wind. The gusts will

catch and move the bow, so you should allow for it.

Now, you let off your gas to idle, and, reach down and snick into forward gear.

Give your engine a little gas to get your boat stopped, then moving again with

some water flowing past your underwater appendages for control.

If you have more wind than usual blowing your bow around, you can once again

call upon your Two-Fisted Docking techniques. Here you angle your rudder and

your outboard in a direction to power the bow into the wind. You will have your

tiller and your outboard throttle arm pointed downwind. This will swing your aft

section with the wind, but pivot your bow into the wind, giving you control

during a critical time when you have stopped, and have no water over your rudder

or keel.

A momentary burst of

power, and, you'll be in control again, moving easily and with purpose down the

channel to the open waters.

A momentary burst of

power, and, you'll be in control again, moving easily and with purpose down the

channel to the open waters.

Two-Fisted Practice: Most sailors find the Two-Fisted Docking falls readily to

hand, but just a little practice will help everyone get a little more

comfortable. While you are at the dock, begin by just sitting in the cockpit.

Unlock the tensioning collar of your outboard - mine is loosened with a simple

butterfly nut - and place your hands on the outboard and the tiller. My right

hand goes to the throttle arm of the outboard; my left rests atop my wooden

tiller.

Practice swinging the outboard throttle arm and the tiller at the same time so

you can achieve about the same angle on both.

When you've had a little dry run, start your engine. You want to acquire a feel

for how your engine and rudder work together. It's possible to leave your dock

lines on loosely during this maneuver.

Begin backing with the rudder and the outboard angled slightly away from the

dock. When you are at the limits of your aft dock line, move the engine and

rudder to angle back toward the dock. Give it a little throttle to get a feel

for the maneuver and to determine the angles you'll need.

All this moving around, back and forth, might look a little odd to bystanders,

but you are getting the practice you need. They'll watch you with increased

respect the next time you dock in confidence in heavy winds.

One cautionary note: keep a spring line on your boat on the dockside, so you

don't run your bow into the slip when you practice. If you are one of these

boaters that have a set of fenders, or other cushions in the front of your slip,

you're ahead of the game.

Now that you've got the hang of things, practice your technique backing out.

Easy does it.

On a calm day, take your boat out alongside a soft buoy, and, just practice

moving your stern back and forth. Get the feel of your boat, your throttle

settings, and, your rudder control. You'll be amazed at what you can do with

your boat, whether it's a centerboard or a keelboat, just pivoting around the

outboard and the rudder at the same time.

If you've gotten confident when using just a little throttle and moving slowly,

pivot your rudder and your outboard, and, give it a little gas. Watch your boat

carve a turn you never before thought possible. It's fun practice, but be

careful. Don't overdo it.

Coming in windy: Many sailors begin to sweat on a crosswind docking into a slip.

A wind will whip across the bow, sending a nicely piloted boat off course, and,

maybe even headed toward the boat next to you.

First of all, be aware that there's a difference between docking on a port or a

starboard slip. Some sail boaters request a home slip that is on the shore side.

If you are coming in from the lake, and, you have to make a starboard landing

into your slip that is on the lake side, you have a greater boat-handling

problem than a shore side landing does. All the shore side landing has to do is

helm a gentle arc and the boat will nudge its hull into the slip and everyone

grins how easy it is.

Coming off the lake if you have a lakeside finger slip, you have to cramp the

boat into the slip at a greater angle and at the same time, miss the boat on the

opposite slip. No easy curve for you: when you get in close, you cut in sharp,

ease the throttle so you don't bang into the dock ahead of you, and, you loose

steerage as you slow. It gets a little tricky when there's a wind up.

Here is where your practice with Two-Fisted Docking really pays off. As you near

your slip, you begin your turn a little later than usual. You give yourself a

little room by coming in on the opposite side of the channel from your dock. You

cock your outboard and your rudder and give your engine a little gas. You'll

need to adjust your angle and your power as your stern swings around, but watch

your bow carve neatly into your slip.

Even with gusts that might have knocked your bow off course, you have managed to

bring your boat into your slip successfully.

More Two-Fisted Procedures: Though it's possible to gain lots more control with

Two-Fisted Docking, you still need to have practical procedures to cope with

other docking problems during really heavy weather.

More than one skipper has approached a dock only to have a gust of wind cross

the bow and feel his boat take a heart-stopping skid toward an opposite docked

boat. While this drama was playing itself out, the skipper's stalwart crew

waited patiently and wonderingly, lines in hand.

But nothing else.

Onboard Persistence, I carry two boat hooks, one of which is always in its

holder beside the starboard cockpit seat, and, within easy reach. This is an

aluminum boathook, with telescoping rod and with a nylon hook on one end beneath

a rubber tip. Coming into a slip in blustery conditions, a boathook can make all

the difference.

Using Two Fisted Docking, I might be able to get the bow around on a really

windy day, but I know that I will have only a precious few moments until I get a

line on a dock cleat. With a boat hook, I can easily reach for a cleat, pull the

boat alongside, and, get my docking line on. If I am not single handing, a

crewmember can reach out and grab the dock, pulling the boat in.

Equally important, if the boat comes into the dock and is blown away, I can

calmly wait and fend off an opposite boat using the rubber tip. An easy shove or

two, and, we have a line on the dock forward or are headed back toward our own

side of the slip. Getting blown off the dock doesn't happen to me much, but when

it does, it's a comfort to know that I know what to do and have a boat hook

handy and that the situation is in control. No worries mate.

Once we get close enough to dock, a crewmember can step ashore and tie up the

boat properly. We use four lines: two forward lines, one aft line, and, a

midships spring line. Many boats don't know how important a midships' spring

line can be, both to hold a boat in position at the dock as well as for

maneuvering during heavy weather.

The midships' spring line is especially important in an offshore docking on a T

dock. With an offshore wind - wind blowing away from the dock - you will use it

to advantage as a final phase of your docking. You'll make your approach using

your Two-Fisted steering to give you lots of control, swinging the bow into the

dock. You can get a loop of your boat's spring line over a cleat with your

boathook or by hand. Now you can power ahead, with a little cock of your rudder

and outboard tiller toward the dock. The boat will slide ahead, and, tethered by

the midships line, will swing nicely alongside the dock. Keep a little power on

to keep the boat in position. Your crew will step ashore lightly and put on the

forward and aft dock lines. Naturally, you had fenders over the side beforehand.

If the wind is gusting onshore - toward the dock - docking is relatively easy.

Just make your swing, using your two-fisted techniques, and the wind will carry

you into the dock.

However, if you are going inside the T dock, and, you have an onshore wind,

you'll need a few more precautions since the wind can now carry you into other

boats, or, onto the shore. Here you make your Two-Fisted Turn around the end of

the dock and head directly into it. Hold your bow to the dock under power while

a crewmember secures a docking line from the bow to a dock cleat. The length of

this line should be about the beam of your boat, plus a few extra feet.

Once the dock line is on, throttle down and let your boat drift back with the

wind. Once you have some tension on the docking line, put your engine into

reverse and aim the prop and the rudder toward the dock. Give the engine a

little gas and, using the dock line as a pivot, watch your boat swing broadside

into the dock.

Put a midships line,

with a large loop, on your boathook and place the loop over a dock cleat. You'll

drift out a bit, but snick the engine into forward, and add a little throttle.

You'll lightly power forward, and, as you do so, your boat will swing into the

dock, now secured by a bowline and a midships line. Swing your outboard arm and

rudder tiller to point toward the dock, pushing you to the dock, and put on your

aft line and adjust and retie your bow and midships lines.

Put a midships line,

with a large loop, on your boathook and place the loop over a dock cleat. You'll

drift out a bit, but snick the engine into forward, and add a little throttle.

You'll lightly power forward, and, as you do so, your boat will swing into the

dock, now secured by a bowline and a midships line. Swing your outboard arm and

rudder tiller to point toward the dock, pushing you to the dock, and put on your

aft line and adjust and retie your bow and midships lines.

Now you can look around to see if there are any admiring, or envious glances,

from your fellow boaters.

Two-fisted docking is easy, natural, and works wonders. Once you get the hang of

using your rudder and outboard in combination to get away from a dock, as well

as to land, you'll breathe a lot easier when you get into a heavy weather

docking situation.

A handy boat hook doesn't hurt any, either. That's Two Fisted Docking as well.

Marlin Bree is a frequent contributor to Northern Breezes and is the author

of four books about boating, including his latest, Wake of the Green Storm. (see

www.marlinbree.com). His sailing adventures during Superior's "Perfect Storm"

are included in a new nonfiction anthology from International Marine publishing,

Treacherous Waters: Stories of Sailors in the Clutch of the Sea, garnered the

publisher says, from "the best writing about sailing and the sea from the past

40 years."