|

Adventure Bound: A Father and Daughter

Circumnavigate the Greatest Lake in the World

By Carl Behrend

CHAPTER 11--TROUBLE

Morning came. Naomi and I

had slept under the stars in our sleeping bags.

We awoke to the lapping of the waves on the

shore. There is nothing I have ever experienced

like camping on the Lake Superior shore. We

crawled out of our sleeping bags and decided to

walk to the store to buy a couple of last minute

things we needed. We would be sailing into some

remote areas where it would be days, or weeks,

before we’d have any chance of re-supplying.

We had been invited to eat

breakfast with the folks we had met the night

before. So on our way back to the boat, we

stopped by their campsite. But we found them

still asleep. Naomi and I decided it was time to

get moving. The southwest wind continued to blow

as it had the day before, pushing us past the

old Grand Marais, Michigan Coast Guard Station.

I knew the building well. My son Caleb and I had

repainted it the summer before. While working

there, we learned many stories of the courage

and valor of the lifesaving crews.

|

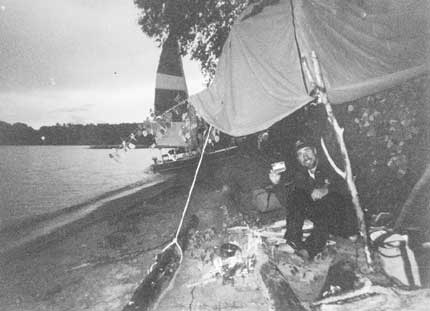

| Escaping a thunder storm in one of our

hastily built shelters with a hot cup of

mocha and a small fire. |

As Naomi and I sailed by

the Grand Marais Harbor entrance and headed

east, I recalled the story of the Parker for

her. They say the ship was pounded by a

southwest wind back in 1907. The old wooden

steamer began to sink while it was heading for

shore. The captain blew the ship’s whistle,

which alerted the Grand Marais lifesaving crew.

After a tiring 50-minute row, the lifesavers

reached the vessel.

Not able to carry all 17 of

her crewmen, the Parker’s yawl was launched and

eight of her crew followed. The ship sank soon

afterward. After several hours of rowing against

the wind and waves, the two boats neared the

harbor. Two tugs picked up the tired rowers and

towed them in to shore.

Naomi and I sailed east.

The southwest wind was quite strong and seemed

to be getting stronger. We sailed past the spot

where Caleb and I had stopped to repair the

damaged jib the year before. Naomi and I made

good time. When we reached the Two-hearted

River, we decided to pull in and take a little

break. As we were eating lunch, I noticed a

sailboat about a half-mile offshore. The

occupants of the boat seemed to be having

difficulty. It looked as though they had lowered

the sail and were trying to start their motor.

But they were stuck in the high wind and waves.

As I was watching them, their situation seemed

to be getting worse. I ran over to the boat and

got my radio. I had a small hand-held unit. I

turned it on. I watched the boaters for a few

more minutes. Then I heard the harbormaster of

the Little Lake Marina trying to reach the

sailboat on the radio. The marina was located a

mile or two away from us. I spoke to the

harbormaster briefly and told him I had been

watching the boaters too. He said he could go

out and assist them in his Boston whaler

powerboat, which is a very seaworthy craft.

The harbormaster had been

trying to contact the boat for a while. But

there had been no response. We watched the

boaters for a while longer. Apparently, they got

their motor working and started making some

headway going west.

I was standing at the very

spot where one of the old lifesaving stations

along the Shipwreck Coast had been standing in

1875. There were four stations in all. They were

located at Vermilion Point, Crisp Point,

Two-hearted River and Muskallonge Lake at Deer

Park. How many times had the brave men here

witnessed ships in distress? In the early days

of shipping on the lake, there were so many

shipwrecks along this coast that these four

manned lifesaving stations were built about 10

miles apart. History has largely forgotten these

“storm warriors,” which was the nickname given

these members of the U.S. Lifesaving Service. A

24-hour beach patrol would walk the shore

continuously. They would meet between stations

and exchange a token, proving they had made

their rounds. If they should see a ship too

close to shore, or in danger, they would light a

flare to warn them of danger or to acknowledge

their distress. How many times had they launched

their surfboats to row through breaking waves to

rescue ship’s crews? I felt their awesome

responsibility for a few minutes while I stood

there.

Today was not a good

day for me. It was one of those days where

nothing goes right. The windbreaker Daddy got me

blew off the boat, which perturbed me greatly

because I really, really liked it. The flies

were terrible and ate me up. And when we finally

made camp I lost my glasses. So I’m really in a

bad mood. I need to pray about this because I

don’t want to be like the children of Israel

(complaining).

As far as progress

goes, we did pretty good. We ate breakfast at

the diner in Grand Marais. It was a really cool

restaurant and I had some French toast. We

pulled out of Grand Marais about 10 a.m. and got

to Whitefish Point about sunset. On our first

stretch, the waves and wind were erratic and

puffy. But then after we stopped at the mouth of

the Two-Hearted River, things calmed down a

little.

The wind blew more

steady and the waves turned into huge rollers.

It was a long boring stretch between Grand

Marais, Michigan and Whitefish Point.

When Naomi and I finished

our lunch, we set sail again. By now, the waves

were 4 to 5 feet high. The winds were quite

strong. So we had reefed the mainsail. Naomi and

I launched the boat, sailing past Little Lake

toward Whitefish Point. With the lake getting

rougher, we tried to stay a bit closer to land.

Unfortunately, we had trouble on the other side

of Little Lake. We were trying to make it around

a small point of land when our rudders hit

bottom. This caused them to kick up, making it

very difficult to steer.

In the heavy seas and

strong winds, all I could do was run the boat up

onto the shore. Fortunately, this is one of the

best features of a catamaran-the ability to

beach. With some difficulty, we pulled the boat

up. There we were on a narrow strip of beach

right near the pounding surf. We did not want to

stay there. We set our sails to tack into the

wind and decided to launch out into the

breakers. If we got caught sideways in these

waves, the boat would surely be pounded to

pieces. Would we make it back to deep water? Or,

would this be the end of our trip?

The wind caught our sail

and pulled us through the breakers and finally

into deep water where I could lock my rudders

down. We cleared the point and we were on our

way. We made good time with following seas,

stayed farther out from shore and we had no more

problems that day.

Crips Point Lighthouse

was a welcome sight with its lone tower,

contrasting boldly against the dark sky.

We sailed past the old Vermilion Point

Lifesaving Station and on to Whitefish Point. As

we got closer to Whitefish Bay, we could see the

lighthouse tower reflecting in the evening sun.

The winds were dying down and the waves were

beginning to calm. We could now relax a bit.

With Whitefish Point now in

sight and the seas running a bit more calmly, I

was able to tell Naomi of another interesting

story.

“It happened right out

there,” I said, pointing. “About a mile and a

half offshore, it was the strange story of a

shipwreck, believe it or not.”

The crew all got off in the

lifeboats and the captain went down with his

ship. But the captain was the only one who

survived.

“How could that be,” Naomi

asked?

Well it happened like this,

there was another November storm in 1919. The

186-foot wooden steamer-the Myron-was towing

another ship called the Miztec. But the pounding

of the waves caused the ship to leak badly.

Hoping to make it around the point, Captain Neal

of the Myron dropped his towline and ran for

shelter. But the ship was in serious trouble. A

passing ore carrier called the Adriatic,

noticing the ship was in trouble, pulled

alongside to protect her as the Myron

desperately tried to reach safety.

The Vermilion Point Coast

Guard sailors also noticed the ship’s plight and

launched their lifeboat through the terrible

surf. Only a mile and a half form the point, the

little ship gave up. As the Myron began to sink,

her crew climbed into the lifeboats. But Captain

Neal decided to go down with his beloved ship.

Meanwhile, the men in the

lifeboats were in a desperate situation. The

deckload of lumber now awash in the pounding

seas hammered the lifeboats. The Adriatic made

several attempts to rescue. But when the big

ship began to hit bottom, the captain retreated

her to deeper water.

Another ship, the 520-foot

H.P. McIntosh actually drew close enough to

throw lifelines to the survivors. But weakened

by the freezing cold, they were unable to save

themselves. The captain of the McIntosh, fearing

for his own ship and crew, had to pull away. The

Coast Guard crew, likewise, was unable to

penetrate the pounding debris. All 16 crewmen

perished.

Meanwhile, Captain Neal had

gone down with his ship. But as the ship sank,

the pilothouse popped off and Captain Neal

climbed onto the roof of what had become a

makeshift raft. For 20 miserable long hours he

drifted in the storm.

The next day, the captain

of the W.C. Franz spotted a body on some

wreckage. He turned his ship to pick up the

body. To his surprise, he saw the body move.

Captain Neal was rescued, barely alive. His body

was some 20 miles from the wreck, but he

recovered and was actually the only member of

the ship’s crew who survived.

“Wow! That’s a great

story,” Naomi said.

We sailed for the shore and

pulled the boat up onto the beach near the

lighthouse. Naomi and I unloaded our gear and

set up camp. It was a beautiful evening. The sun

setting over the big lake and the distant

mountains on the Canadian shore left a lasting

impression of the awesome beauty of Lake

Superior.

We stopped twice today

after the Two-Heart before reaching here.

Hopefully, God will bless again tomorrow. It was

another beautiful red sunset again tonight and

there was a freighter inching its way across the

horizon. We had macaroni and cheese for supper.

Yummy.

This is the

sixth of a series of excerpts from Carl Behrend’s

book Adventure Bound. For more information on

how to purchase books, CD’s or to arrange

bookings call (906) 387-2331 or visit www.greatlakeslegends.com.

TOP

|