|

Key wave concepts

by David Dellenbaugh

Waves are like snowflakes. No two

are exactly the same, and therefore

you have to treat each one as a unique and

different entity. The same is true in the

big picture—every sequence of waves

you face during a race will be at least a

little different from anything you have

ever seen before. So you must continually

work at finding the optimal path

through the waves you face.

When you get to the race course, it is

helpful to ask a few questions to understand

the waves and how they will affect

your race:

• What's causing the waves? The size

and shape of waves will depend on

whether they are caused by wind, current

or boats. You could have smooth swells

from a storm far away, steep chop when a

strong breeze blows over shallow water

or when current flows against the wind,

or random chop from motorboats in a

spectator fleet.

• Are the waves the normal size that

you would expect for the wind velocity? For various reasons, the waves might be

larger or smaller than normal (see below).

This could have huge implications for

steering, trimming and sailing the boat.

• Are the waves perpendicular to the

wind direction? If the waves are flowing

in the same direction as the wind, then

you will generally have symmetry from

tack to tack. But If not, you will need to

set things up differently on each tack.

• Are you going faster or slower than

the waves downwind? Figure out if the

waves are helping you (i.e. they're going

faster than you) or hurting you (you're

faster than them). Also, do surfing conditions

exist? This is key to knowing if you

are allowed to pump your sails. Here are

further explanations of some of these

concepts.

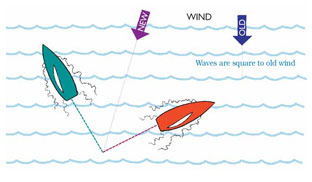

Check for wave asymmetry

Check for wave asymmetry

When you're racing upwind, are the waves equal on each tack? They are usually similar on port and

starboard tacks because waves are created by the wind and therefore they come from that direction.

However, this is not always the case. Sometimes the waves are not perpendicular to the wind, and

this can have a huge impact on the way you sail your boat.

There are several reasons why waves may be different from tack to tack:

• Windshifts - If the waves are at first aligned with the wind, any change in wind direction will

make them unaligned (at least for a while).This is very common.

• Presence of nearby land - If there is land to windward of the course, it could affect how waves

move across the racing area.

• A distant storm -When you're racing on the ocean, there are often swells coming from a direction

that's very different from your sailing wind.

• Cross-current - If you have a strong current that is not aligned with the wind, it often creates

waves that aren't square to the wind.

When you first start sailing in your race area, check to see if the waves are the same on each

tack. If not, make the appropriate sail trim adjustments. For example, you will have to make your sails

fuller and more twisted on the bumpier tack (which goes more directly into the waves). On the other

(smoother) tack you may be able to trim your sails much flatter and tighter. You can point higher on

this tack, too, and keep your weight a little farther forward.

There are also strategic implications of wave asymmetry. For example, if port tack is smoother

it might mean the wind has shifted to the right. When wave asymmetry is caused by a persistent

windshift, it's better to sail the smoother tack first since that will take you in the direction where the

wind is shifting.

Motorboat waves

It would be hard to run most sailboat races

without motorboats, but it sure would be nice if

we could run them without motorboat wakes!

Unfortunately, waves from motorboats are a

fact of life in most racing venues, and the good

sailors simply figure out how to handle them.

Motorboat waves differ from wind generated

waves in several important ways. They are

often steeper and closer together (and therefore

can potentially hurt your speed much more).

Boat waves typically hit you at strange angles

(rather than straight with the wind). And, fortunately,

they usually come and go pretty quickly.

The first rule for maintaining speed

through waves is to hit them at an angle

(instead of head on).This is normally worth

doing even if it requires a significant alteration in

the course you have been sailing. In fact, it may

even make sense to tack or jibe so big waves

hit your stern rather than your bow.

The second rule of thumb for motorboat

waves is to make sure you are going fast just

before you hit them. In other words, be proactive

by bearing off (or heading up on a run),

easing (or trimming) your sails, moving weight

aft, etc. Don't wait until the first wave hits you

before making these changes!

As I mentioned above, you ideally want to

hit motorboat waves at an oblique angle and

fully powered up. But sometimes you can't do

both. When the waves are coming at you parallel

to the wind, you have to make a choice. It's

usually better to hit waves at an angle even if

you have to pinch up and lose a little speed.

This seems better than bearing off for speed

and hitting the waves head on.

Waves relative to wind

In any wind velocity, there is a certain size and

shape of waves that you normally see with that

amount of wind. In a five-knot breeze, for

example, the water surface should be almost

totally flat. In 18 knots of wind, however, you

expect to see fairly good-sized waves with

whitecaps.

But as every sailor knows, you don't

always get 'normal' sea conditions. You might

see bigger or smaller waves than what's typical

for that wind velocity, and this will affect how

you set up and sail your boat.

When I'm racing, I categorize the wave

state in three general ways:

1) Normal waves for the wind; 2) More

wind than waves; and 3) More waves than

wind. Here's a closer look at each.

'More wind than waves'

This is almost always a fun condition for sailing

(unless you're trying to do a windy jibe). It's

great (or painting and speed, and makes staying

in the 'groove' pretty easy.

Here are several times when you are likely

to see this condition:

• A building breeze—the breeze is up but

the waves haven't had time to build yet

• An offshore breeze—the water is flatter

as you get closer to land because there is less

'fetch' for the waves to build.

• Current flowing with the wind.

When you have more wind than waves,

you can trim your sails flatter and harder than

you normally would in that breeze. You should

sail most boats as flat as possible and go for

maximum height (pointing).

'More waves than wind'

This is almost always a tough condition for sailing

(unless you are sailing downwind with

enough breeze to surf). It makes finding the

groove difficult, and it quickly separates the

good sailors from the rest.

You will typically see this condition with:

• A dying breeze—the breeze always

changes faster than the wave state.

• An onshore breeze—when the wind is

blowing toward the shore, it usually has a long

'fetch' for the waves to build.

• Current flowing against the wind.

• Lots of motorboat wakes (the worst!).

When you have more waves than wind, be

careful about trimming too hard or pointing too

high. Err on the side of twist, power and footing

so you keep going fast

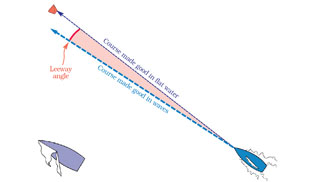

Watch for leeway caused by waves

Watch for leeway caused by waves

Waves make sailboats go up and down, and they also push boats to leeward.

The difference between the course you steer and the course you make good

through the water is your leeway angle. The size of this angle is a result of

many factors such as heel angle, wind velocity, boat design and wave

height. Though leeway for racing boats is usually not more than a few

degrees, it will get slightly larger as the waves get bigger.

The main place where you will notice leeway is in relation

to fixed objects like marks. Your laylines are wider, for

example, in waves, so you must allow a little extra

distance before tacking.

One place where it's easy

to see how much the waves push

you to leeward is at the starting line.

When boats attempt to luff in place on the line,

they often slide much farther to leeward than

they think. That's one reason why there

is often a significant line sag when the

waves are big.

Go fast upwind

in waves

Except for those few times when you

are able to ride a motorboat wake

coming from behind, waves are never

helpful when you're racing upwind. It's

always faster to sail in flatter water, and

that should be your first rule of thumb

on beats.

Sailing fast in waves requires a

team effort that involves the driver.

trimmers and the rest of the crew. You

have to look ahead for waves that are

coming, shift gears and find the best

way to steer through them.

There are three basic strategies for

dealing with waves upwind. You can

sail directly through the waves, steer

over the waves, or try to avoid the

waves. More likely, you will do some

combination of the above.

Going straight through waves is

usually the best option when the waves

are everywhere and too small to steer

around. The bigger and heavier your

boat, the more likely you are to take

this approach since it's often impossible

or slow to turn your rudder for individual

waves.

This is not a great option for bigger

waves, but sometimes it is your only

choice (e.g. when all the waves are big

and steep!). In that case, try to keep the

boat going a little faster than usual up

the beat. The most costly mistake is to

be too slow when you hit a bad wave.

Anticipation is important. The key

to maintaining speed through bad

waves is to shift gears before you get to

them. That means you need enough

warning to power up your sail plan

before the bow digs into the first wave.

Steering over the waves is a good

idea when they are larger and spaced

farther apart, and when going straight

through them is slow. The smaller and

lighter your boat, the more effective

this is.

The basic technique for sailing

over waves is to head up on the front

side and bear off the back side. In other

words, luff toward the wind a little as

you go up the wave and then bear off

away from the wind as you go down the

back side. The steeper the wave and the

faster your speed over the waves, the

more sharply you will have to turn your

helm and your boat.

In boats that are light enough to be

affected by the positioning of crew

weight, combine the steering with a

rotational movement of your bodies:

Lean aft (and maybe in a little) as you

go up the wave. Then lean out and forward

as you go over the top and down

the back side.

Avoiding waves is always the preferred

option. This works well when

you have identifiable areas of bad

waves, such as boat wakes or sets of

especially large, steep waves. Since

you can never avoid all waves, you

must use this in concert with other

ways to sail through waves but this

strategy should always be a part of your

upwind plan.

The techniques that work best in

waves are often subtle enough that you

never know how well they are working

until you measure your performance

against nearby boats. So test your wave

strategy before the start and continue to

evaluate it during the race. If you're not

fast, change something and try again!

Put your weight in the right places

One of the reasons why waves make a boat go

more slowly is because they cause it to 'hobbyhorse,'

which disrupts the air flow around its

sails and the water flow around its foils. This is

especially harmful in lighter air.

The main goal of positioning your weight

in waves, therefore, should be to reduce hobbyhorsing.

Keep your crew together as much as

possible and near the middle of the boat. In light

air, the ideal spot is right at the top of the keel,

since that is the point around which the sail

plan, hull and foils pivot. When conditions are

bumpy and light, it's not unusual for crews to sit

down below on the cabin sole (in bigger boats)

or to crouch down inside the cockpit (onedesigns).

This reduces the range of motion of

the mast and keel/centerboard.

In heavy air the crew can't be inside the

boat, of course. Instead they should sit tightly

together like the crew on the boat above. The

fore-and-aft position of their weight depends on

the boat, wind strength and wave shape.

Generally, the crew should be at least slightly

farther aft when it's rough (than when it's flat

with the same wind velocity) to keep the bow

from plowing into waves.

If you're racing upwind in waves and you

think your weight is positioned perfectly but you

aren't going fast, try moving your crew a little

farther apart. Sometimes the boat doesn't 'click'

with the natural frequency of the waves—but

different crew spacing may improve this harmony

(and therefore your speed!).

How much to steer in waves!

When you're sailing upwind, waves will

always slow you down, so you should avoid

them as much as possible (see below).

However, when you turn your rudder to steer

around waves, the drag you create will also

make you go slower. Therefore, you are always

searching for the optimal tradeoff between

using a lot of rudder and missing waves versus

using less rudder and hitting waves.

The only true way to judge whether you

are doing a good (fast) job of this is by comparing

your performance to that of a nearby

boat. That's why it's critical, when you have

waves, to train with another boat if possible and

to tune up with a competitor before every race.

While you are doing this, try different steering

techniques to see what is fastest in the unique

conditions that you have on any day.

The last thing you

want to do in a

wavy race is

to be looking

for

the groove as you come off the starting line.

Several factors influence the tradeoff of

how aggressively you should steer (i.e. how

quickly and how far you should turn the rudder).

Here are two important considerations:

• Size and shape of the waves - Are the

waves big, small, rounded or crested? How

steep and close together are they? You don't

have to steer much in small waves or even big

swells, but medium-size waves can present a

tough challenge, especially when they're steep

and/or close together,

• Characteristics of your boat - Is your

boat large or small (relative to the waves), light

or heavy? Does it turn easily? Does it have a

narrow bow that cuts easily through the waves

or a fat bow that slams into waves? All these

factors affect the tradeoff of hitting a wave versus

turning to miss it.

One thing that's true for all boats and

waves is that when you turn the boat, it's best

to do this with as little rudder as possible.

Reduce drag by steering with sail trim and body

weight. For example, use windward helm to

allow the boat to carve its own turn to windward

on the front of the wave. Then, at the top of the

wave, hike out hard and ease the mainsheet or

traveler to help bear off down the back side. If

you can turn the boat without so much drag,

then the tradeoff moves in the direction of steering

to miss more waves.

Dave publishes the newsletter

Speed & Smarts. For a subscription

call: 800-356-2200 or go to:

www.speedandsmarts.com

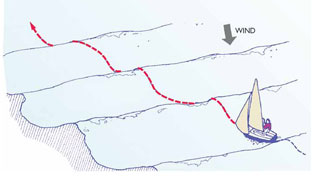

These waves are unusually large, uniform and rounded on top, so it's not necessary to

steer around them very much. The ideal course would be a gradual, slight arc to windward

on the approaching face of the wave, followed by a similar bearing off down the back side.

TOP

|