Cruiser’s

Notebook: Mastering the Mast

By Cyndi Perkins

Stepping and unstepping the mast are necessary tasks

for sailors planning to cruise eastern North

America’s canals and rivers. Count on Captain Scott

breezily assuring all who ask that it’s a piece of

cake, nothing more than a half-hour job. Count on me

rolling my eyes behind his back when he offers these

words of wisdom.

It’s true that the stick goes down or up in short

order. The basic requirements are a crane and

willing hands. It’s the work before and after that

is time-consuming. The 47-foot deck-stepped mast of

our 32-foot DownEast Chip Ahoy has been

through 10 steps/unsteps. I was on hand for each,

with the exception of the initial raising when

Captain Scott bought the boat at Brennan Marine in

Bay City, Michigan.

More than a decade after Chip Ahoy’s

launching, our 2006 sailing explorations found us

slowly chugging against an opposing current on the

Hudson River, homeward North during our second

navigation of America’s Great Circle Loop. By this

time, lowering the mast - as well as dealing with

the inconveniences of carrying it on deck - was Old

Hat. Not fun, but not a heart-thumping ordeal. And

this time we had extra help. Our 24-year-old son

Scotty had joined us at Solomon’s Island on the

Chesapeake Bay to complete the journey to Lake

Superior. This would be his first experience taking

down the stick.

As we hung a left off the Hudson and entered

Catskill Creek in upstate New York, my first

priority was not mast-dropping in preparation for

entering the Erie Canal. I was on a mission to find

a hot, clean shower. The last time we’d stopped

anywhere with shower facilities was on Saturday, May

27 in Annapolis, Maryland. It was now Saturday, June

3. Going even one more day with dirty hair was not

to be endured. Skipping regular shampoos makes a

cruising woman crabby. And a bucket bath or

sunshower won’t suffice in chilly, rainy weather.

Our sail up the Chessie and through the C&D Canal

was relatively uneventful. But we’d had a romping,

rough sail skirting the crab pots down Delaware Bay

followed by a grueling overnight passage in pea-soup

fog coming into New York Harbor. After a night of

tensely tracking and reporting our position to avoid

colliding with considerable shipping traffic, we

hove-to off Sandy Hook in the damp dawn, biding our

time until the fog lifted from zero visibility to a

pathetically better-than-nothing five feet. Entering

the giant NY port half-blind was made even more

dramatic when exiting U.S. warships jammed our radar

and GPS and sent police boats zipping over to warn

us against venturing closer to the impressive

behemoths. Chip Ahoy skimmed just outside of

the buoys, giving the military flotilla a wide

berth. A cabin cruiser disoriented in the murk

without radar meekly trailed in our path.

We rested just one day at the Statue of Liberty

anchorage before traveling up the Hudson to the

Haverstraw Bay anchorage where we were blasted by a

spectacular thunder and lightning storm. Another day

of slow travel with a top speed of only 4 mph

brought us to the rickety but welcome floating dock

of Mariner on the Hudson Restaurant at Highland

Landing, across from Poughkeepsie, New York. Here a

night’s sleep can be had with purchase of dinner.

There were no entrees under $18 on the menu, but

price be damned, Captain Scott and I greatly enjoyed

our Lobster for two garnished with shrimp, mussels,

clams and pasta. We also splurged on Blue Point

oysters while Scotty pronounced the mozzarella

sticks with fresh marinara sauce the best he has

ever had. And my, the cold beer tasted fine!

On the previous Loop we had taken care of mast

business at another Catskill Creek facility,

Hop-O-Nose Marina. Its shower wins my vote as the

worst on the entire Loop. There were other

spider-infested and unspeakably filthy contenders,

but Hop-O-Nose’s decrepit bath house won by virtue

of a faucet that spewed freezing water into the

shower stall and refused to turn off. I was chilled

to the bone by the time I got out of there. New

marina owners in 2004 had promised a better facility

was in the works, but that was still not the case in

2006. This boater doesn’t always mind roughing it,

but if I am going to pay $1.75 per foot per night

for dockage, I darned well better be able to take a

decent shower. So we decided to switch it up and try

Riverview Marine Services, where venerable Lake

Superior cruisers Bonnie and Ron Dahl had been

berthed when we passed by on our previous trip.

Boaters should be prepared for a powerful current on

narrow Catskill Creek, especially during periods of

heavy rainfall. When the creek and tidal Hudson are

approaching flood stage, the tides become

unpredictable. Call or radio ahead to your marina of

choice to request docking assistance and watch out

for other boaters who may lose control of their

vessels in the unexpected swirls and eddies. As we

docked in close quarters we had to fend off a small

power boat caught by surprise and swiftly pulled

into our stern.

Riverview’s bathhouse-laundry room was as immaculate

as promised with plenty of hot water. Consummate New

Yorker Mike and his fine crew couldn’t have been

more pleasant or accommodating during our two-night

stay. We enjoyed roaming around the hilly town,

where fuzzy white windborne seeds snowed upon us and

the landscape was green and blooming, scented with

apple-blossoms, early roses and budding peonies. The

old-school brownstone and gingerbread Victorian

architecture is lovely, but there are areas where

one should not venture alone, especially after dark.

We stuffed ourselves at the Village Pizzeria

downtown on a super-sized authentic New York pie and

spicy chicken wings.

Between loads of laundry and a stab at provisioning

- there is only a small convenience store with very

little grocery selection downtown - we unhanked and

stowed the sails and re-assembled the mast cradles

that Captain Scott built in Hammond, Indiana on Lake

Michigan at the start of our journey. The three

supports at the bow, deck center and stern are

easily bolted and bracketed together. We had to take

a very expensive taxi trip to a lumberyard to

procure our materials. Some facilities that step

masts actually have cradle “graveyards” where

boaters may forage for suitable lumber or existing

cradles. One of our previous supports was acquired

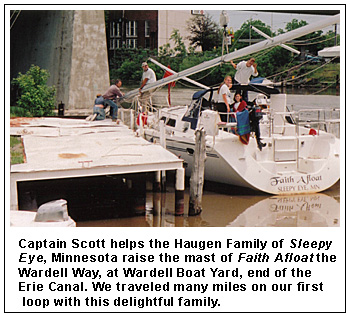

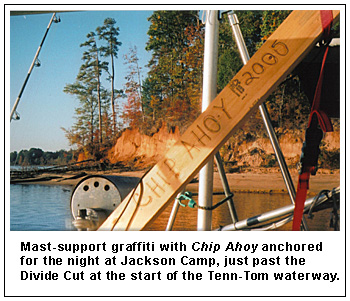

at Hop-O- Nose after a boat named Indian Summer

made use of it. We later left it for recycling

at Wardell Boat Yard at the end of the Erie Canal.

Like Indian Summer we left our name and

travel path magic-markered on the cradle. Who knows,

we may see it again in future travels!

Experience has taught us to carry a saw and power

drill aboard. Captain Scott also has cradle

dimensions sketched out to ensure the structure

height will allow us to keep our full dodger up. On

our first Loop we traveled the entire river system

without any shield from the elements. It was quite

uncomfortable at times.

Disconnecting and bundling the rigging is a

painstaking job that requires organization and

attention to detail. We have specific containers for

cotter pins and the like to ensure that everything

that is taken off goes back on just so. Down in

Florida on our first Loop we met a couple who lost

their mast in the middle of the night on the Gulf of

Mexico. The captain had not heeded the warning at

Turner Marine Services to double-check his cotter

pin replacement.

While I bow to Captain Scott’s acumen in handling

all of Chip Ahoy’s operating systems, I do

admit to extreme displeasure with his untidy habits.

We have seen many boats carrying their masts neatly,

even attractively, with every strand of rigging

immaculately secured, padding perfectly placed,

decks cleared for easy access during locking. Not on

our boat. We’re as unkempt as the Beverly Hillbilly

Clampetts, loops of rigging spaghetti popping out

everywhere, old pillows shoved under the mast, odd

bits of rope, bungee cords and sail ties holding

everything together. We duct-tape a plastic back

over the mast bottom to keep out nesting birds and

insects. Maneuvering around the mess takes some

getting used to. It really doesn’t matter, as long

as everything is secure. But it gnaws at my anally

retentive nature!

Captain Scott just laughs at me. And I must admit

that he has a point. We had to assist two boats

transiting the Erie Canal with us because their

beautifully presented mast-carrying systems did not

hold up in waves and wake. In one case there was so

much stress on the cradle supports that it cracked

one of them. A sailboat traveling with its mast down

is extremely vulnerable. As Captain Scott points

out, you are really nothing but a “slow power boat

with a battering ram.” The slightest motion could

tumble mast and rigging overboard. Some boaters

carry their mast on the port or starboard side. But

this limits your ability to tie up on whichever wall

is open in the sometimes crowded locks and places

the mast in close proximity to the water - where you

don’t want it to end up if you get rocked.

Mike himself mans the crane when it is mast-stepping

time at Riverview. After consulting on a good tide

time for pulling into the well, we cleared the deck

of jerry cans, our trusty bike and other flotsam,

positioning the dinghy where it wouldn’t get in the

way. In the well, Scott disconnected the stays. He

had loosened them in preparation for the drop but

always waits until the last minute to take them off.

With true chivalry Mike suggested that Scott and

Scotty stay aboard with his crew member while I put

the camera to use ashore. I was more than happy to

be excused from my usual duty of stabilizing the

mast amidships while it is being lowered. Mike’s

number-one concern is safety, so he doesn’t permit

anyone forward after the crane strap is secured and

the initial lifting/lowering begins. After the mast

was freed, he calmly instructed the guys to guide it

into horizontal position. For us the trickiest part

of this process is preventing the mast top from

clunking into the wind generator and solar panel

astern.

Mike’s biggest piece of advice? “Keep a cool head.

Nobody should get excited.” He asked us to “send a

few more boats my way,” and we are happy to oblige.

If you stop at Riverview Marine Services, be sure

and tell Mike that Chip Ahoy sent you!

When traveling with a mast on deck, be prepared to

sit out anything but nearly flat or totally calm

seas. The term “canal” is deceptive. You will

encounter sections of wide-open water. Bone up on

your charts and guidebooks so you’re ready. If you

see any whitecaps when approaching these areas,

definitely stay in port. Much to Scott and Scotty’s

chagrin we were delayed by rough conditions on

Oneida Lake in the Erie Canal system. The lockmaster

at Lock 22 had warned us about the waves but my two

bold and impatient men remained willing to stick our

nose out on the small but feisty lake until a couple

of sailboats ahead of us tested the waters and were

forced to beat a hasty retreat. We stayed two nights

on the free pier at Sylvan Beach. We were delayed

another day when attempting to exit the Oswego Canal

for the necessary jump across Lake Ontario into

Canada’s lovely Trent-Severn Canal. On our first

try, Chip Ahoy and a buddy boat manned by

singlehander Todd O. Smith of Wabasha, Minnesota

bashed into two-to-three foot seas that had looked

deceptively calm until we passed the harbor

breakwater out onto the Great Lake. I couldn’t even

bear to look at the teetering mast until we inched

our way back into calm water. We licked our wounds

at the $1 per foot Oswego Marina where I took

advantage of another good hot shower and clean

Laundromat while Scott and Scotty further reinforced

the cradle system and shifted the mast back to a

stable position.

Should your mast be subjected to any stresses, I

highly recommend that you use your time in port to

make necessary adjustments. In any case, the entire

mast cradle system should be checked thoroughly

several times per day as part of your maintenance

routine.

Putting the mast back in its proper place is always

a relief. On Friday, June 23 we stepped at the

excellent Bayport Yachting Centre in Midland,

Ontario just off Georgian Bay, located next to our

accommodations at the hospitable Midland Sailing

Club, where we were hosted by friends Doug and Helen

Hill of Misty Blue II. The club has its own

crane for do-it-yourselfers but it is a members-only

service due to liability. No worries, Bayport’s

staff made the process as easy as possible. Scotty’s

young muscles came in very handy when it came time

to attach the backstay. A sailboat again, we were

set for our next big leg of the journey, across

Georgian Bay into Lake Huron and from there up the

St. Mary’s River to the Soo Locks and our own sweet

Lake Superior.

Ups & Downs

Here are some major considerations to take

into account when stepping/unstepping your

mast:

Cost: Prices vary considerably and by

region, ranging from roughly from $4-$9 per

mast foot - more, if you are also going to pay

to have it prepped and secured for travel.

Some yards charge a flat fee for crane use,

generally $50 per hour and up, and a flat rate

for personnel, also in the $40-50 per man per

hour range. Tuning the rigging is often an

additional charge but worth it if you have an

expert available who can teach you how to get

the most out of your sailing system. Tipping

for a job well done is also appreciated. Even

if you do not choose a do-it-yourself

stepping/unstepping option you’ll want to be

on hand to lend a hand and take care of any

last minute details, for example disconnecting

any wires at the base of the mast.

Mast Transport: Some boaters choose to

ship the mast to the location where they will

be putting it up. It is expensive, but

advantages include not worrying about the

stability of the mast on board, having plenty

of wiggle room for docking and locking and not

hitting your head on the darned thing!

Trucking fees vary. On our first cruise down

the rivers we met two Ohio sailboaters who

teamed up to ship their masts down to Turner

Marine on the beautiful Dog River near Mobile,

Alabama, splitting the roughly $1,800 cost.

Boaters may be charged a mast storage fee at

some yards if the mast arrives before they do.

Communications: Obviously you can’t

sail with your mast down, but also remember

that anything you have mounted on the mast,

including the marine radio antenna and mast

light, is also disabled. A radio is essential

for contacting locks and finding out the

intentions of tow-barges and dredges. Captain

Scott mounts a spare radio antenna on the aft

mast cradle. When anchored we hang a portable,

strong white light as high as it will go atop

a jury-rigged pole of PVC pipe on the stern.

Since our radar is independently mounted off

the stern, that isn’t a problem for us, but

would be a consideration if your radar is

mast-mounted. On the up side, when the mast is

down it is an opportune time to replace light

bulbs, wiring, spreader boots and any other

accoutrements that need attention.

Anchoring/docking: Anchoring is a

different beast with the rigging down,

especially when winching up. Be mindful of the

shift in stress points on your vessel and when

at all possible make use of marinas or free

docks. When docking, be cautious of your

temporary “battering ram” and attempt to keep

it from protruding over walkways. We attach a

red cloth to alert fellow boaters and passerby

to the obstacle. The flag is also a handy

“spot” to help you compensate for overhang off

the bow when docking or locking. Be extra

careful when moving around your boat; you may

be surprised at how many habitual hand-holds

disappear when the rigging is down. The only

thing left to grab on Chip Ahoy’s decks

are the lifelines and bowsprit railing.

Boarding and departures from the boat also

present additional safety concerns.

Facilities: Other cruisers are the most

up-to-date source for deciding where to raise

or lower the mast. When and where you can

raise the stick will also be dictated by

current water levels and bridge clearances, so

keep an ear open for the latest news on the

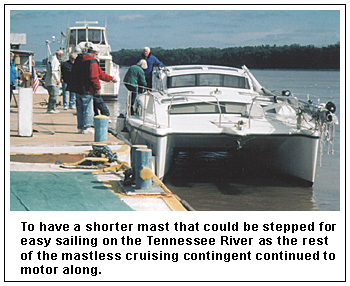

waterway. For example, on the last Loop we

could have stepped at Kentucky Lake, but water

had already been let out to winter flood

levels and there was four feet or less in

available wells, not enough for our five-foot

draft. After raising the mast in Demopolis,

near the end of the Tenn-Tom waterway, we

encountered a bridge that was supposed to open

on demand but was closed down and unmanned due

to construction of a new bridge. Two sailboats

with shorter masts led the way under and

helped us eyeball the situation as we scraped

through by mere inches, brushing but not

breaking the radio antenna.

|

Freelance writer Cyndi Perkins and husband Scott,

Houghton County Harbormaster, have been sailing Lake

Superior for 14 years and completed two

circumnavigations of America’s Great Circle Loop

aboard their 32-foot DownEaster Chip Ahoy. The

couple is planning their next extended cruise south

in 2008. Cyndi will be sharing top boating

destinations with readers in her regular “Cruiser’s

Notebook” feature. Comments, suggestions and

questions (short text messages with no attachments)

may be directed to her at svchipahoy@gmail.com.

TOP

|