|

Great Lakes Captains

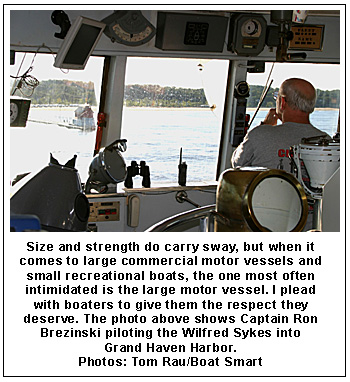

Deserve Utmost Respect

by Tom Rau

While conducting research for my

book, “The Boat Smart Chronicles, Lake Michigan

Devours Its Wounded,” I rode aboard with a number of

commercial captains from large motor vessels to

captains of small passenger-carrying vessels. From

their vantage point on the bridge, I was able to

witness firsthand the ordeals and tribulations

imposed upon them by recreational

boaters—transgressions they must so often bear in

silent indignation. I think the world of these

captains: truly the Great Lakes’ consummate maritime

professionals.

Not only do these professional captains deserve

utmost respect, but more so they deserve a little

empathy from the boating public on the challenges

they face, especially while making port. Let’s go

aboard the motor vessel Wilfred Sykes to walk

a step or two in the captain’s shoes.

The steamer Wilfred Sykes is a 671-foot long

bulk carrier capable of carrying 21,550 tons of

cargo in her six compartments below decks. I picked

the boat up in Muskegon and rode her down to Grand

Haven. We departed Muskegon at sunrise. The Sykes

had dumped a load in the early hours at the VerPlank

dock located at the east end of Muskegon Lake and

was now on her way to the VerPlank docks in Spring

Lake. A two port visit across 24 hours would call

for an 18-hour workday for the crew.

The departure from Muskegon Harbor carried us out

into a placid Lake Michigan. By the time we reached

the waters off the Grand Haven harbor mouth, the

morning sun sat 15 degrees above the eastern

horizon, casting eye-squinting rays across a

glimmering surface.

Despite the fact that the Sykes carried electronic

charts that interfaced with GPS input to pin point a

vessels’ position on a LCD screen, the captain, for

the most part, relied on time-proven methods—reading

nature’s telltale signs.

Captain Ron Brezinski, pointed to the harbor mouth:

“If you look closely you can see darker water around

the harbor mouth. That’s river sediment. Notice it’s

setting towards the south. That means a surface

current that will set us south,” said Captain

Brezinski.

The captain then pointed out wave movement from the

northwest and a slight breeze that brushed surface

waters indicating wind direction. At the moment, a

calm Lake Michigan hardly announced these subtle

movements, but to the veteran captain they seemed

apparent, slight as they might be. All can influence

the large bulk carrier, often in opposing

directions. Imagine the challenge dealing with these

elemental influences while maneuvering through a sea

of boats.

While riding aboard the car ferry Emerald Isle

that runs between Beaver Island and Charlevoix,

Michigan, Captain Kevin McDonough told me while

approaching the Charlevoix harbor mouth he can

experience river currents, lake currents and

wind--all working in opposite directions. At

130-feet long and weighting 380 gross tons fully

loaded, boat handling in a close-quarter environment

can be challenging. Throw in a bunch of recreational

boaters into the mix and watch the sweat flow.

That morning the Sykes’ captain set up an

approach to the Grand Haven harbor mouth three

quarters of a mile out. Captain Brezinski said, “If

I start my final approach too soon I could find

myself making unwanted maneuvers to say on course as

the elements play on my vessel. If I make it too

late I could miss the mouth” One can understand,

then, why small boats can raise havoc once the large

boat commences its final approach. The last thing

the captain needs is to make unnecessary course

maneuvers. Fortunately, most recreational boaters

follow the common sense rule—the rule of gross

tonnage.

Entering the Grand Haven channel the size of the

motor vessel became apparent as we passed the

lighthouse on the South Pier. I’ve passed the light

structure numerous times aboard Coast Guard small

boats and always looked upward at the 51-foot high

cylindrical light that loomed over the Coast Guard

small boat. Now, I was looking down onto the top of

the lighthouse.

Entering the Grand River, the captain piloted

through a series of lateral buoys marking safe

passage through the shoal-ridden waters. He used

landmarks on shore as reference points for the

helmsman to steer on while making slight compass

changes when needed. Like any experienced boat

handler, the captain was a boat length or so ahead

of his position. The maneuver he made now could

moments later raise havoc should he miscalculate

even a subtle course change, especially in a narrow

channel. He certainly doesn’t need recreational

boaters throwing unexpected surprises onto his

tenuous path.

The Sykes does carry a bow thruster a

rotating propeller device located beneath the bow

that allows the captain to pivot the bow left and

right. However, the thruster is of little use at

speeds above three knots, or in winds exceeding

twenty-five knots.

Watching the veteran captain focus on the task at

hand, one would conclude that it was his first

channel transit as a master. Even though he has made

countless passages in his 12 years as master, he

focused on the task at hand as if it the experience

were anew.

Most boaters would be utterly impressed, as I was,

by the professional skills displayed by Captain

Brezinski and his crew. Smart boaters can show their

respect by staying well out of the captain’s

workspace, and I believe most do except for a few

loggerheads. Boat Smart- give them space only a

loggerhead wouldn’t.

Tom Rau is a long-time Coast Guard rescue

responder and syndicated boating safety columnist.

Look for his book, Boat Smart Chronicles, a shocking

expose on recreational boating — reads like a great

ship’s log spanning over two decades. It’s available

to order at: www.boatsmart.net,

www.seaworthy.com, www.amazon.com, or through local

bookstores.

TOP

|