|

Dave publishes the newsletter Speed & Smarts. For a

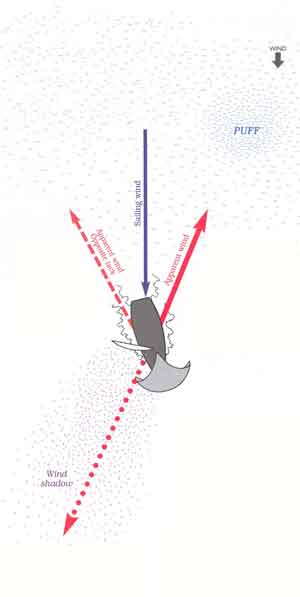

subscription call: 800-356-2200 or go to When you’re sailing on a run, one of the best tactical tools your have is your wind shadow. This area of disturbed air flow may extend many boatlengths in front of your boat and can be used to slow down or control boats that are ahead of you. Because of this, downwind legs are great places to catch and pass other boats.

In order to use your disturbed air advantageously, however, you

have to understand the nature of wind shadows. Many factors

affect the size and shape of the area of “bad air” that is cast

by a sailboat. But the most important thing to remember is that

wind shadows extend away from boats in the direction that’s

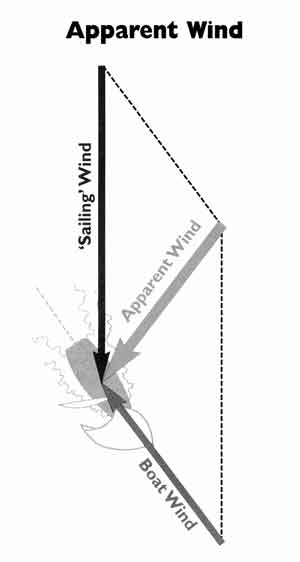

opposite to their apparent wind. Because the apparent wind direction is almost always shifted forward relative to the sailing wind, wind shadows do not extend directly downwind (i.e. to leeward) of boats. Instead, they angle farther aft than most sailors think. That’s why when you want to slow another boat with your bad air, you usually have to position yourself farther forward than you expect. Understanding the nature of wind shadows is obviously important when you are behind other boats and trying to catch up. But it may be even more critical when you are ahead of other boats and trying to keep your air clear.

Locating Wind Shadows In addition to determining the angle of the wind shadow, it’s important to know its size. There are many factors that affect how large an area is covered by a boat’s disturbed air. These include the wind velocity, height of the mast and speed of the boat. The length of a wind shadow is often measured in “mast-height” units rather than in boatlengths. For example, in heavy air a boat’s wind shadow might extend four mast-heights to leeward. In light air, that same boat might cast a wind shadow for eight or more mast-heights. Even if you understand the shape of orientation of wind shadows in theory, this won’t always work in practice. Often when it seems you should be in another boat’s bad air you aren’t, and vice versa. So keep looking for signs while you are racing. Sometimes, for example, you can see or feel bad air in your sails. When a boat is coming from astern, the first thing you may notice is a flutter in the leech of your main. If you are catching another boat, your spinnaker luff may go soft first. The ultimate measure of clear air, of course, is your speed relative to other boats, so keep a close eye on this. If you are going fast, then bad air is probably not a problem. But if you start to slow down, think about wind shadows.

Some apparent observations • The wind pennant on top of your mast points in the direction of your apparent wind. This is the direction from which you will get puffs and lulls. It’s also the place to look when you want to know if you’re getting bad air. If your wind pennant is pointing toward another boat, that’s usually not a good thing. • When you jibe, you will have the same apparent wind angle on the other tack. This line shows where your puffs, lulls and clear (or dirty) air will come from on starboard tack.

• Changes in the strength of the true

wind (i.e. puffs or lulls) can change the direction of your

apparent wind and fool you into thinking you also have a lift or

header. When you get a puff, for example, the wind you feel

shifts aft temporarily until your speed picks up. Be careful

about making strategy decisions based on these “velocity shifts.”

• This is the reciprocal of your

apparent wind. It shows the direction in which your wind shadow

extends away from the boat to leeward. On a run or reach, this

direction can be quite different from the reciprocal of the true

wind. |