|

Electric Yacht: Clean, Green, Quiet.

Product Review by Tony Green

What sailboat system generates

more foul language than any

other? Engines, right? Marine heads

are second and electronics come in

third, especially when owners throw

the manuals away without reading

them.

What sailboat system generates

more foul language than any

other? Engines, right? Marine heads

are second and electronics come in

third, especially when owners throw

the manuals away without reading

them.

As much as we rely on our auxiliary

engines, many of us hate them

with a passion. The vast majority of

sailboat engines are internal combustion

outboards or inboard diesels,

with a few inboard gas motors still

around. What’s not to love? They can

be hard to start and require a warm-up

period, they are sometimes temperamental

and stall at low speeds (usually

when you need them most), both

the fuel and exhaust are smelly and

dangerous, the cooling systems can

clog, maintenance and winterizing

are not trivial and worst of all in the

21st century, they are powered by (gasp)

fossil fuels.

For decades, our paradigm has

demanded internal combustion engines to

meet our needs on the road and on the

water. Electric Yacht of Golden Valley,

Minnesota, is out to change that way of

thinking. The company’s electric propulsion

systems offer a clean, green and quiet

alternative to traditional sailboat auxiliaries

for a large number of sailors.

Chances are you’re one of them.

Electric Yacht was founded in 2007

by Scott McMillan, an electrical engineer

and sailor who began tinkering with

electric motors on his own boats. The

company’s target market is the increasing

number of sailboats with aging inboard

engines that are

in need of overhaul or

replacement. Within

that market are large

subsets of lake sailors,

racers, weekenders

and coastal cruisers

for whom a big diesel

is serious overkill.

Electric propulsion

offers a simpler and

more enjoyable option

for the many boat

owners who only

use their engines for

short distances to get

in and out of the slip,

ramp, mooring or

anchorage.

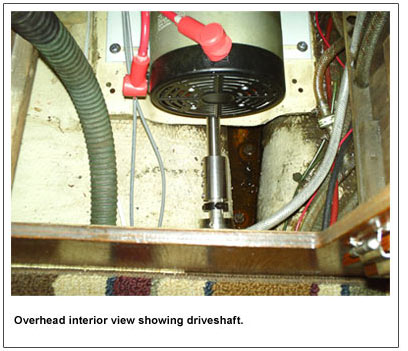

The company’s electric motors

mount to existing engine rails and

propeller shafts. Multiple reduction

ratio options accommodate different

boat and propeller sizes and installation

can easily be done with the boat

in the water. Wiring connections are

simple, with pre-fabricated cables

provided to connect batteries, motor,

throttle quadrant and battery monitor.

An average conversion from

inboard diesel to electric is weight

and cost neutral compared with an

engine rebuild, space is usually

gained and your bilge will never

smell like fuel again. List prices vary

from $3,695 for a Model 100ib (48

VDC, 5 HP) to $5,495 for a Model

260ib (12HP @ 48VDC, 18HP @

72VDC). Horsepower ratings

between electric and internal combustion

are not directly comparable,

since electric motors do not have power

siphoned off for engine-driven auxiliaries

such as cooling pumps, fuel pump, alternator,

etc. Typically, an electric system

can replace a diesel or gas engine of twice

the horsepower without a significant loss

in top speed.

In addition to the Electric Yacht system,

you will need batteries and a charger.

The cost of eight flooded lead-acid batteries

and a charger is about $1,500, while

more advanced AGM batteries with

charger are closer to $2,500. The motor

and controller are basically maintenance free,

although battery management and

upkeep still apply. If AGM or lithium batteries

are used, this can be reduced significantly.

The company has more than 40

installations worldwide and can power

sailboats up to 40 feet long.

In addition to the Electric Yacht system,

you will need batteries and a charger.

The cost of eight flooded lead-acid batteries

and a charger is about $1,500, while

more advanced AGM batteries with

charger are closer to $2,500. The motor

and controller are basically maintenance free,

although battery management and

upkeep still apply. If AGM or lithium batteries

are used, this can be reduced significantly.

The company has more than 40

installations worldwide and can power

sailboats up to 40 feet long.

Electric propulsion’s critics normally

focus on two limitations: lack of

power and range. Sure these systems are

nifty, but can they punch through high

winds, waves or currents and can they

really drive the boat for more than a few

hours? As I would learn, power is not a

problem for Electric Yacht. But range is

limited and there’s just no getting

around the fact that battery technology,

while improving, is the weak link.

Traditional lead-acid batteries are the

most affordable and are widely available.

Lithium batteries are lighter and

have increased life and range, but cost

more. The company is optimistic that

industry investments in hybrid and electric

automobiles will provide much

needed advancement in electrical storage

for the boating market. These

improvements will only increase the size

of Electric Yacht’s target market, and

most boaters should still be satisfied

with today’s technology.

Recharging the batteries is obviously

important and options are numerous.

For a boat in a marina slip, a traditional

shore power charger is normally used.

Boats at anchor or on a mooring typically

use solar panels, wind generators

or a combination of the two. To extend

range indefinitely, owners can carry a

portable gas generator or install a small

diesel generator onboard, although

purists might suggest that this is heading

in the wrong direction. The Electric

Yacht systems can also regenerate

power to help charge the batteries. The

boat’s motion under sail spins the propeller

and shaft, turning the electric

motor into a generator and putting current

back into the batteries.

Recharging the batteries is obviously

important and options are numerous.

For a boat in a marina slip, a traditional

shore power charger is normally used.

Boats at anchor or on a mooring typically

use solar panels, wind generators

or a combination of the two. To extend

range indefinitely, owners can carry a

portable gas generator or install a small

diesel generator onboard, although

purists might suggest that this is heading

in the wrong direction. The Electric

Yacht systems can also regenerate

power to help charge the batteries. The

boat’s motion under sail spins the propeller

and shaft, turning the electric

motor into a generator and putting current

back into the batteries.

I met Scott McMillan, company

President and Chief Engineer, and

Bill Tomlinson, Director of Marketing,

for a test sail on Lake Koronis in central

Minnesota. This 3,000-acre, five-mile long

lake is the perfect application for

this technology. Scott’s Catalina 27 is

kept on a mooring and the motor is used

to get on and off the buoy and for sunset

cruises and quiet puttering around the

lake. The boat normally sits all week

while a wind generator recharges the

batteries and is more than ready for the

next weekend. That use pattern

describes a lot of sailboats out there,

mine included.

There would be no puttering for our

test run. The lake was whipped up by 15-

knot winds with gusts over 20. We were

shivering in the cold October rain and

northeast wind, but I was secretly pleased

to see how Electric Yacht’s equipment

performed in a healthy breeze and chop.

Scott got us underway with a turn of the

key. There was no warm-up required and

full power was instantly available, even at

low speeds. A low hum let me know that

the motor was on, and the tone changed

with RPM, giving good feedback that the

controller was responding. While not

silent, it was much quieter than a diesel,

and we easily carried on a conversation

inside the cabin with the motor running.

The Catalina effortlessly plowed through

the building waves and hit hull speed with

plenty of reserve. So much for the concern

about being underpowered. Battery

condition and discharge rate were visible

at a glance and the cockpit monitor displayed

amps and time left on the battery.

At high speed the readout said we had 2.5

hours left, plenty of time to get off the

five-mile lake in a hurry if we needed to.

Backing off the throttle increased our

time remaining and the monitor was

instantly updated. Motoring at a couple of

knots in a dead calm provides more than

eight hours of run time on a full charge.

When it was my turn to drive, I put the

motor through its paces and Scott even let

me dock his boat in the wind and waves

to test maneuverability. The single-lever

quadrant was similar to operating an

inboard auxiliary, without the fear that the

motor would stall if idled down in gear, as

internal combustion engines can do.

I came away convinced that this

technology is well designed, affordable,

easy to install and more than capable to

meet many sailors’ needs. Evaluating

these systems requires an honest analysis

of what type of sailing you really do.

Long-distance voyagers will probably

stick with fossil fuels, since they pack

more power per pound than batteries. In

my opinion, electric propulsion should be

considered by the high number of sailors

who day sail, race, weekend or coastal

cruise within a few miles of shore and just

don’t run their engines that much. The

benefits are many. Instant on with no

warm-up time. No more trips to the fuel

dock. No oily bilges or fuel and exhaust

fumes in the cabin and cockpit. Peaceful

motor-sailing. Clean. Green. Quiet. Isn’t

that what sailing is all about anyway?

More information, including specifications,

pricing and customer testimonials

are available on the company’s website

at www.electricyacht.com

Tony Green has been boating since

1985, including eight years on U.S. Navy

nuclear submarines. He currently teaches

for Northern Breezes Sailing School and

sails with his wife and two daughters on

Lake Calhoun in Minneapolis, on the St.

Croix River and on Lake Superior.

TOP

|