|

Cruiser’s Notebook:

Lake Superior stop part of Alaskan sailing couple’s harbor hop ’round the world

by Cyndi Perkins

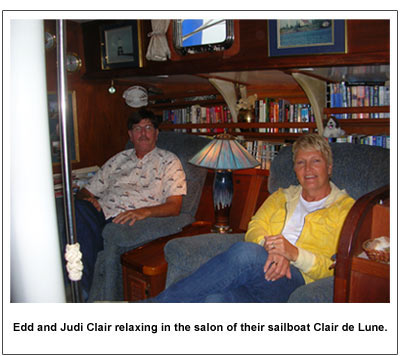

On a rainy autumn Monday at the

Lake Linden Village docks in

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, the cruising

sailboat “Clair de Lune” of Anchorage,

Alaska is defying the calendar. Weathered

in by a cold front, Edd and Judi Clair

delayed their departure until early

October. By then most Lake Superior

sailors have yielded to the season, lifting

out for the winter or heading for warmer

climates as the geese fly South. In comparison,

Clair de Lune, a 1976 Valiant 40,

is considerably behind schedule.

On a rainy autumn Monday at the

Lake Linden Village docks in

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, the cruising

sailboat “Clair de Lune” of Anchorage,

Alaska is defying the calendar. Weathered

in by a cold front, Edd and Judi Clair

delayed their departure until early

October. By then most Lake Superior

sailors have yielded to the season, lifting

out for the winter or heading for warmer

climates as the geese fly South. In comparison,

Clair de Lune, a 1976 Valiant 40,

is considerably behind schedule.

Edd and Judi are not particularly

concerned about delays. “I’m from here

and we lived in Alaska, so we know about

weather,” says Judi. They heartily

embrace cruising off the beaten path, traveling

at Mother Nature’s pace. Their

secret to enjoying a live-aboard lifestyle

is meticulous preparation followed by an

easygoing attitude and sense of humor

toward dealing with whatever comes up.

True cruisers know that something

always comes up. If it’s not an operational

thing, it’s a weather thing.

After totally refitting their boat

(more about that later), the Clairs

embarked on a shakedown cruise to

Hawaii and back. Then they pointed the

bow south again, heading from Alaska

down the California/Mexico coast. An

interesting west-to-east transit of the

Panama Canal followed. After exploring

“the other side,” Clair de Lune sailed

across the Gulf of Mexico into the Eastern

U.S. river system. Awaiting game ensued

as spring floods impeded their progress

upriver through the lock system that

begins in Mobile and ends in Chicago on

Lake Michigan.

Edd jokes that he could write a book

titled “Doing the Loop the Wrong Way.”

Even after the floodwaters receded in

spring 2008, swift and powerful opposing

currents made for slow going. Clair de

Lune completed just 77 miles on her first

three days headed up the Mississippi

River, negotiating tow barges, logs and

other debris while avoiding fast-forming

ever-shifting shoals on hairpin curves.

Judi’s top piece of advice for safely navigating

the rivers is “Follow the charts, not

the buoys.” In some stretches of the

rivers, there are more buoys washed

ashore than in the water while others are

submerged.

From the Great Lakes, the couple

was in a good position to head in direct

yet leisurely fashion to the Caribbean for

the winter.

But first came a mandatory and

delightful side trip to Judi’s home waters.

The couple harbor-hopped from the Soo

across Lake Superior to the Keweenaw

Peninsula’s Portage Lake Shipping Canal

and into Torch Lake, where they tied up

and plugged in at Lake Linden Village’s

municipal docks in September rather than

July. “We thought we’d be here on the

Fourth of July. We were delayed by flooding

on the Mississippi,” says Edd. “For

seven weeks we waited on Kentucky

Lake.” While in the Land Between the

Lakes area in Kentucky the couple with

the help of a visiting granddaughter managed

to adopt two adorable turtles who

are with them still, contentedly clambering

about in a sturdy glass bowl. “We are

trying to find a good home for them,”

laughs Judi, explaining that a visiting

grandchild talked them into taking on the

amphibians. In addition to visits to and

from family, the layover also including a

side trip to Nashville, Ten., where Clair

de Lune found plenty of water for its six foot

draft, a hospitable town dock and

convenient public transportation to local

attractions.

Edd, originally from California, has

sailed for many years, breaking away

from it to spend several years focusing on

work and family. Newbie Judy took an

ASA sanctioned liveaboard sailing course

in Seward, Alaska. She sincerely recommends

the investment. “It was good for

me to learn it on my own,” she says. After

successfully completing the course and

having fun doing it, she decided that

cruising on a sailboat would be fulfilling.

She didn’t think Edd was going to jump

on her enthusiasm and buy “THE” boat as

fast as he did, but when he accelerated the

project she willingly kicked in her talents,

including sewing.

The times that they are able to set the

sails and let the autohelm pilot in the

tradewinds are among Edd and Judi’s

favorite sailing experiences. With an

autopilot and windvane for self-steering,

Clair de Lune does quite well on her own

in favorable conditions. Her best performance

was wing-on-wing most of the way

from California to Hawaii. “We hardly

changed the sail set,” says Judi. Edd says

it turned him into a “Gentlemen Sailor.”

“For 11 days I had hardly anything to do.”

Because he now strongly favors downwind

routes, Judi predicts that a global

circumnavigation is in their future.

The legs of the Clair’s cruising journey

thus far are San Diego to Hawaii in

17 days, followed by a 26-day sail back to

Alaska, then back down the coast to

“Frisco Bay” where they stayed for six

months before continuing on to Mexico

and the pleasures of the Gold Coast,

including Barra de Navidad. “The Gold

Coast was a fantastic experience,” says

Judi. In Barra 100 boats anchored in a

protected bay created the kind of atmosphere

that exemplifies the cruising

lifestyle. After listening to the cruiser’s

net on the radio each morning, to hear

news of arrivals, departures, requests for

help and random equipment for sale, the

Clairs eagerly awaited the local bakery

boat for fresh-baked bread. Judi says she

loves the “experiences of everything”

when encountering towns and villages

she has never seen before. “If you’re

going past, you’ve got to see this stuff,”

says Judi. “We’re cruisers. That’s what

we do.”

Edd has picked up quite a bit of

Spanish, and has found that “as long as

you try a little” communication in foreign

countries doesn’t need to be a stumbling

block. “Costa Rica, Mexico, Panama …

We’ve had great experiences everywhere.”

After experiencing Central America

and transiting the Panama Canal, Clair

De Lune crossed the Gulf of Mexico to

Mobile, Alabama. Edd’s 83-year-old

mother Kitty was aboard for the entire trip

from the Panama Canal to Mobile. She

had always wanted to experience the

canal and once that was completed there

never seemed to be a convenient time to

stop in a port and ferry her to an airport.

Besides, she truly loves living aboard, say

son and daughter-in-law. “She’d live on

the boat with us if we let her,” says Judi.

“In the locks we couldn’t count an 83-

year-old as a line handler. She was our

photographer.”

In 2008 it cost $605 to take a 40-foot

sailboat through the Panama Canal.

Passing from the Pacific to the Atlantic is

done in one day, an estimated 51-mile

nine-hour trip. Boaters who miss a lock or

otherwise get stuck overnight pay a $300

fine. Chugging

across Lake Gatun

their guide started

telling them that

they weren’t going

to make the lock in

time. Eight knots is

the recommended

speed. “We don’t do

eight knots,” says

Edd. Clair de Lune

valiantly plowed

toward deadline at

6.5 knots. “We

pushed it,” says

Judi. They made it.

In addition to

time limits on the

Panama Canal there

are requirements for

lines, bumpers, line

handlers and a hired

guide. There are

three locks up and

three down. Boaters

should expect to

encounter giant cargo vessels at any time. Rafting of

smaller vessels is required, and the

bumper of choice is tires wrapped with

packing tape. In keeping with the cruising

spirit of teamwork, boaters with tires they

have no further use for willingly pass

them on to new arrivals. With so many

boaters willing to help each other out, a

Panama Canal passage is not as daunting

as it seems. “It went smooth as silk,” says

Edd. “We hired an agent for $300 but we

could have done it ourselves and we will

do it on our own on the way back through.

He did do all the paperwork.” Contrary to

the widely held belief that it takes a long

time to get permission to transit, the

Clairs say their passage was arranged

almost too quickly to physically prepare

for it. A fellow cruiser pitched in as one of

the required line handlers, another common

practice among transiting boaters.

Judi said it was definitely helpful for Edd

to go through the canal crewing on another

boat before piloting Clair de Lune.

Their local hired guide Julio was “a real

nice guy,” she says, and it was easy

enough to supply the required three meals, water, soda pop and coffee for the

crew as they made their way through the

famous channel.

Clair de Lune’s free and much easier

journey up the Portage Canal to Lake

Linden was a homecoming for Judi, with

the docks located just a few miles from

the little town of Laurium where her

mother Leona Walkonen still lives. The

couple enjoyed great time with family

and friends and were able to make one of

Leona’s wishes come true after Judi

learned that the Portage Lake Lift Bridge

operators wouldn’t be annoyed to lift the

largest, heaviest lift span in the world for

the 57-foot keel-stepped mast. “My mom

wants to go under the bridge,” explains

Judi. Since it would be a leisurely three hour

trip out to the north entry of Lake

Superior and back, obtaining a couple of

lifts on demand was not a problem. Leona

got her wish in early October, after Clair

de Lune stopped for a pumpout and diesel

at Houghton County Marina. A couple of

days later the Clairs took a weather window,

heading for the Soo in favorable

although distinctly not balmy conditions

on Oct. 9. They were looking forward to

shedding the fleece and socks. “We just

do warm now, there’s no reason to be

cold,” says Judi.

Clair de Lune’s free and much easier

journey up the Portage Canal to Lake

Linden was a homecoming for Judi, with

the docks located just a few miles from

the little town of Laurium where her

mother Leona Walkonen still lives. The

couple enjoyed great time with family

and friends and were able to make one of

Leona’s wishes come true after Judi

learned that the Portage Lake Lift Bridge

operators wouldn’t be annoyed to lift the

largest, heaviest lift span in the world for

the 57-foot keel-stepped mast. “My mom

wants to go under the bridge,” explains

Judi. Since it would be a leisurely three hour

trip out to the north entry of Lake

Superior and back, obtaining a couple of

lifts on demand was not a problem. Leona

got her wish in early October, after Clair

de Lune stopped for a pumpout and diesel

at Houghton County Marina. A couple of

days later the Clairs took a weather window,

heading for the Soo in favorable

although distinctly not balmy conditions

on Oct. 9. They were looking forward to

shedding the fleece and socks. “We just

do warm now, there’s no reason to be

cold,” says Judi.

The couple did enjoy returning to

Alaska as cruising tourists, especially in

Kodiak, which they say is expensive but

friendly. “We recommend it — there is no

better place to check out whales, bears

and eagles — but it cost $9 for a shower

at the Laundromat. It was $6.75 for a

washer and $8 for a dryer.”

The couple planned to decide on a

route out to the Atlantic once they reached

DeTour at the east end of Michigan’s

Upper Peninsula. Unlike boaters who prefer

sheltered grounds, both of them speak

reverently and fondly of long passages on

wide-open water. To reach the Atlantic,

possible routes include the New York

canal system through Oswego after venturing

across Lake Huron, Georgian Bay

and Lake Ontario. Or they may have chosen

to retrace the Great Lakes-river system

route with favorable currents. When

it comes to cruising style, the Clairs prefer

anchoring out to staying in a marina.

From January-May 2008 they spent just

15 days in marinas. While at anchor they

take the dinghy ashore as needed for provisions

or excursions. To get around on

land they use their folding bikes, or walk,

rent cars or use the courtesy cars available

at some marinas.

For Hurricane Season the options

include Bonne-Aire (St. John’s) or

Corozal, Belize. Edd noted that it’s very

important to keep the insurance company

happy by ducking below or above the

storm lines during the most threatening

times of the year.

On overnight passages, the Clairs

have settled on a watch system that works

for them. Edd is a night person and Judi is

a day person, so she begins watch after

dinner and ideally stands until midnight.

Edd takes over until dawn. During the day

they play it by ear, taking turns to nap as

needed. “We try to do six on and six off.

The goal to short-handing is to feel good

so that you can do your part,” says Edd.

“You don’t have that third person.”

The sail system is designed for efficiency

and safety. “When conditions warrant

we snap on,” says Ed, “but my theory

is to avoid going on deck. All lines for

every routine operation are in the cockpit.”

The couple was able to put so much

thought into a designing the boat to their

specific needs because they began from

scratch. Claire de Lune was rudely used

in the cleanup of the 1989 Exxon Valdez

oil spill then left to rot in a boatyard for

nine years. “The boat was a derelict when

we bought her. There was an oil slick

instead of an engine,” says Edd. “There

was no useable plumbing, just mold and

mildew.” The exhaustive two-year rehab

and retrofit including installing a Perkins

4-108 diesel. Wisely remembering that

“all work and no play” is no fun, the couple

stowed work materials out of sight

and continued to entertain family and

friends in the boat as-is throughout the

project.

A wind generator, solar panels, 17-

gallon per hour watermaker and other

amenities render the couple self-sufficient

for six months, in keeping with their general

cruising theme of proper preparation

to prevent poor performance. Because

they don’t like to be cold, the Clairs outfitted

their boat with a Wallace forced-air

diesel heater. “I think it’s the best on the

market,” says Edd. “Instead of turning off

it goes to idle, so it never does cool down

and restart. It’s very economical to run.”

Clair de Lune carries an EPIRB and

a life raft as well as redundant paper and

electronic charts and GPS systems, single

sideband and a variety of means to obtain

up-to-date weather info. The communications

system enables them to keep in regular

touch with family, including their son in Anchorage, daughter in Des Moines,

and three grandchildren

Benchmarks of a true cruiser include

a willingness to cheerfully admit to running

aground or dragging anchor. The

Clairs admit to several groundings, and

proudly report that in all eight instances

they “got off by themselves.” For anchors

and tackle they carry two CQRs, a

Danforth, a Bruce-style claw and the

appropriate chain-rope set-ups, along

with a hydraulic winch to assist in the

hauling. One of the biggest anchoring

challenges was Hawaii, where the Clairs

say they found cruising friendlier than

anticipated but not a good place to stay on

the hook for an extended period of time.

“There’s lot of surf,” notes Edd.

The Clairs began their travels with

St. Bernard Sophie, who became ill and

sadly perished. They cherish their boat

dog memories, including how such a

large dog managed could magnificently

manage to make herself so comfortable

on a sailboat. But they aren’t looking for

any other pets — besides the aforementioned

turtles — “until we’re land lubbers

again,” says Judi. Too many countries

have pet quarantine requirements.

In the future, the couple plans on

traveling back through the Panama Canal

“and then we’ll get lost in the South

Pacific for a while,” says Judi, obviously

relishing the thought.

“We have been rediscovering ourselves.

There is stress but it balances out.

We both saw chiropractors when we were

constantly at work. We are in better health

than we were 10 years ago,” she says.

On November 24 I received an

update on the Clair’s progress. They were

in the river system at Kentucky Lake, on

the Tennessee River headed for the Tenn-

Tom waterway. They reported some very

cold nights but little drama, save for an

autopilot failure on Lake Michigan that

diverted them to Holland, Michigan.

There are repair services and marinas

available in the area but Edd said he was

able to use on-board spares, completing

the repair “in just a couple of hours.”

Having started the Loop the wrong way,

Clair de Lune has set sights on doing it

the “right way,” closing their loop with a

trip up the East Coast of the U.S. and into

the Hudson River at New York Harbor.

Upriver they can catch the Erie Canal and

start working their way back to Lake

Superior. First of course comes the winter

in the Caribbean. For snowbound sailors

that is a delightful thought.

“Off the water, we have had fun also

since leaving your area,” wrote Edd and

Judi. “We flew to Anchorage with our

daughter and her family and visited our

son and his family for a week. Then

returned to our daughter’s home in Iowa

for another week of grand parenting. In

Alaska, we had all three grandkids there

for a week. Very special.

“That’s all our excitement for now.

More to come.”

Cyndi Perkins and husband Scott,

Houghton County Harbormaster, have

been sailing Lake Superior for 14 years

and have completed two 6,000-mile passages

of America’s Great Circle Loop

aboard their 32-foot DownEaster Chip

Ahoy. Opinions expressed by the author

are solely hers and not necessarily the

opinion of Northern Breezes magazine.

TOP

|