|

THE OLD MAN AND THE INLAND SEA

A survivor’s tale of extraordinary courage and resourcefulness on Lake Superior

by Marlin Bree

Copyright 2007

|

Note: This remarkable true-life survival story set on Lake Superior’s rugged North Shore won Boating Writer’s International

grand prize award in 2008. Excerpted from Marlin Bree’s book, Broken Seas: True Tales of Extraordinary Seafaring Adventures, it appeared in the January/February issue of The Ensign magazine, the publication of the U.S. Power Squadron.

|

Jeanneau America announces the arrival of the exciting new Sun Fast 3200 to North America. Fast and fun, this new design offers racers an affordable option for a high performance race boat with a comfortable interior. Chosen as the 2008 "European Yacht of the Year" under 10 meters, the Sun Fast 3200's North American debut will be at the US Sailboat Show in Annapolis this fall.

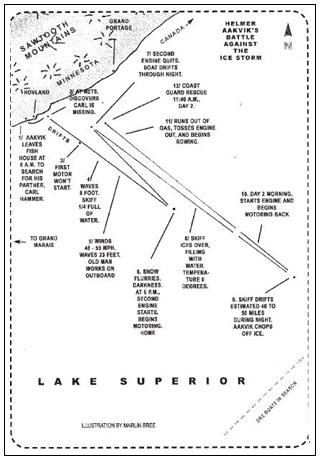

Lake Superior’s chill waters were an ominous slate gray and the lake was steaming with fog banks 40-feet high as Carl Hammer slipped into his 17-foot wooden fishing skiff and started his outboard engine. It was 7 a.m., November 26, 1958 — the day before Thanksgiving.

The 26-year-old North Shore fisherman figured he’d get to his offshore fishing nets before a storm came up, pick his catch, and get back quickly — just as he’d done hundreds of times before. He’d have to hurry.

At 8:30 a.m., his fishing partner, Helmer Aakvik — also known as the “Old Man” — peered out the window of his cabin on the bluffs overlooking Superior and made his decision: he would not go out to the nets this morning. The 62-year-old Aakvik settled down to enjoy a second cup of coffee when his cabin door opened with a blast of wind and his neighbor, Elmer Jackson, charged in. “The young fellow is still out on his boat,” Jackson said, worried.

Aakvik looked up, troubled. A storm was coming on — one of the worst kinds — an offshore wind from the north-northwest. His fishing partner, Carl Hammer, was still out on treacherous Superior. He abruptly put down his coffee cup. “Call the Coast Guard,” he said.

As he turned to leave, Jackson looked at him carefully. “Just don’t you go out,” he warned.

Grabbing a jacket and pulling his cap down tightly, the Old Man walked down the winding path to the bluff’s edge. There was a steady wind out of the northwest, and, even in the protection of the rocky ridge behind him, the temperature was dropping. This was late November in the North Country and soon there’d be ice and snow.

On a near-vertical rock ledge jutting above the lake, he came to the ramshackle wooden fish house that he and Hammer shared. In the open end of the shed, he could see that Hammer’s boat was gone. Spruce trees swayed ominously below in the onshore breeze.

On a near-vertical rock ledge jutting above the lake, he came to the ramshackle wooden fish house that he and Hammer shared. In the open end of the shed, he could see that Hammer’s boat was gone. Spruce trees swayed ominously below in the onshore breeze.

He ducked back inside the wood shack and checked around. Sure enough, the young fisherman had helped himself to Aakvik’s gas supply. The borrowing was OK — they shared supplies all the time in this close-knit Norwegian community. The problem was that Hammer had a new outboard engine that used a different ratio of oil to gas in the fuel than Aakvik’s. The Old Man had an old Lockport and an elderly Johnson,

but Hammer used a newer Johnson, which needed about a half a quart of oil mixed in five gallons of gas. Aakvik’s old two-cycles required twice that amount of oil, and a too heavy oil-gas ratio would gum up his friend’s carburetor and foul his spark plugs — stalling his engine.

He peered into the can, then swirled it around. He could see the drops of water on the surface. His gas was old and had accumulated water condensation. The old man’s normal routine was to filter the water out of the gas so that it didn’t freeze in the lines and kill the engine.

Hammer hadn’t filtered his gas.

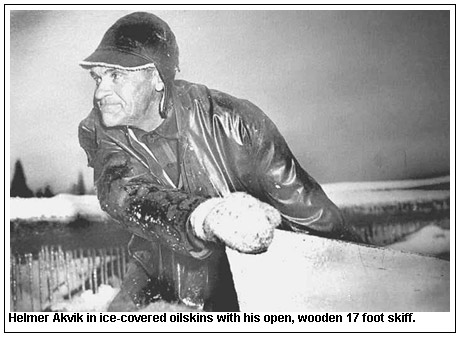

The Old Man hurriedly dressed himself in layers of wool: socks, underwear, pants and shirt. Wool was the key to survival on Superior because it could keep him warm even when it was wet. Over his wool, he put on his heavy rubber fisherman’s suit, adding rubber boots, wool mitts and a sheepskin helmet. He waddled when he walked, but he wore a proven North Shore outfit.

Aakvik never went out on that lake, winter or summer, without a good set of oilskins. Oilies were part of the equipment you needed for survival on Superior, especially late in the season when the famed “Witches of November” came calling.

As he told everyone in his broken English, “they saved your life.”

A little past 9 a.m., the Old Man stood atop the rock outcropping over the slide. His seventeen-foot-long boat was tied to a wooden slide about 30 feet above the water, located high above the shoreline rocks. Mercifully, the wind was blowing from the northwest, off the land, and not from the water. Today, there would be no problem launching the skiff.

The slide consisted of three trimmed tree trunks, each about eight to ten inches in diameter, and over forty feet long. As he attached a wire cable to his skiff’s bow, the Old Man thought for a moment and reached down and threw a hatchet into his boat. Then he added two more pieces of equipment: an old wooden fish box that weighed almost 50 pounds, and, fifty fathoms of rope.

Ready for his battle, the Old Man lowered his skiff down the boat slide into the dark waters. As he hefted himself aboard, the little skiff bobbed up and down a little to welcome his familiar weight. The Old Man felt at home. He had built his boat along the lines of a North Atlantic dory, with a raked bow, slab sides, and, a flat transom. But his North Shore

skiff was much more heavily constructed. It had a heavy wooden v-shaped chine bottom, strong sawn ribs, a beam of five feet, with freeboard of a little less than two feet.

A really good skiff reminded the Hovland, Minnesota, fishermen of boats from “the old country” — a high compliment. Like the Norwegian small boats operating in icy fjords, a Superior boat had to deal with big water — split the waves when it encountered big water, rather than trying to plow through them, and, have enough flare in the bow to lift the boat up so it didn’t founder.

His skiff was more than 20 years old, and, was well beyond a North Shore fishing boat’s useful years. It was tired: it had punched through countless waves, survived many storms, and had been dragged countless times up the slide with a full hold of fish. It had rot in some of the bottom planks, and, the screws holding the planks to the frames felt a little loose.

But the Old Man had faith. His home-built skiff had taken him out and brought him back every time. It could be relied upon to do it once more.

The first blasts of the offshore wind hit him once he left the protection of the shore, and, even in his oilskins, the Old Man felt its bite. There was no protection in the open boat and the wind was coming up sharply. The temperature was about six degrees above zero, and, it was dropping.

Atop a wave, he saw the first marker buoy flag, and moments later, he could make out a line of bobbing buoys, strung out in a row, the line bending in the wind and the waves. But no sign of Carl Hammer or his skiff. In the mounting waves, Aakvik made his run alongside the line, being careful not to foul his propeller on the nets.

At the end marker buoy, Aakvik scanned the horizon. Out here, the big lake was alive. Away from shore, the waves continued to build, and, his small boat bobbed up and down. He held his cupped hand to his eyes, to give him better vision. Still no sign of Hammer or his skiff.

One thing was certain: Hammer had not tied his boat to one of the marker buoys held in place by the heavy rock anchors — standard practice if a fishing boat had engine trouble — to await rescue.

One thing was certain: Hammer had not tied his boat to one of the marker buoys held in place by the heavy rock anchors — standard practice if a fishing boat had engine trouble — to await rescue.

The Old Man pulled his boat alongside a buoy, grabbed it for a moment, and turned off his engine.

And waited.

Along the bluffs on shore, the watchers with binoculars scanned the broken seas. The heavy rollers of Superior were high and mean now, with waves rearing into the lake’s notorious “square rollers.” Visibility was poor, but the wind was coming up and blowing the fog around in patches. Someone shouted that he had seen someone moving alongside the nets.

Word had spread. The village knew that the Old Man had gone out to bring in The Kid.

Someone recognized Aakvik’s boat bounding up and down in the waves. He appeared to be hanging with his hands onto a buoy.

Minutes passed and they saw his boat move away from the nets. From the way his boat was handling, they could tell he was drifting, without power.

Aakvik deliberately was moving with the waves and the wind. He figured that The Kid must have had a problem with his motor and that by drifting without power the Old Man would be carried by the wind and waves in the same direction. The wind speed was about 38 mph. He went down into the trough of one wave, then upward. His boat perched high atop a big breaker.

He did not know how high the waves were, but moving walls of water surrounded him, and they were growing.

He tried to figure the speed and direction his partner was drifting. Once he got his bearings, he started his engine, running downwind, steering clear of the crests. He had to hurry.

When he was about seven or eight miles out, he let his boat idle atop a wave for one last look around for his missing partner. At this height, he thought he could see for miles, but there was no sign of Hammer.

The waves whistled, he noticed — he’d never heard them that bad before.

The waves whistled, he noticed — he’d never heard them that bad before.

It was time to head back toward shore. He could not see the tall headlands of home in the fog, but he knew which way to go: upwind.

He’d have to turn his boat around and plunge directly back into the mounting wind and waves.

Suddenly, the outboard started to splutter, then die. In the eerie silence, he turned to his outboard and saw it was white with ice. He had been using the elderly Lockport outboard without its cover, and, the entire engine had been splashed with spray, which had frozen.

He wound up the starting chord, pulled out the choke, and, turned up the throttle to start. He gave it a hard pull, and the old engine wheezed several times. Again and again, he ran through the starting drill. But the ice-encrusted engine would not start.

He sat back for a moment, weary, but thankful he had the foresight to bring his spare engine onboard. The newer 14- horsepower, two cylinder Johnson twocycle lay in the floorboards.

In the storm-filled seas, in a bouncing boat, he ‘d have to wrestle the heavy Lockport off the transom. Timing his movements between the waves, he unscrewed the clamps that held the Lockport to the transom and grunted: it was frozen to the boat. He hefted his weight against the hundred-pound

engine, felt the ice break, and, leaned over to grasp the power head. He pulled hard and the old outboard came out of the water. He wrestled it to one side and into the bottom of the boat.

Watching his weight, he slid forward to pull the Johnson toward him, carefully lifting it in his arms, cradling it like a baby. His boat, and his salvation would depend on this engine. In the bilge, the partly frozen water sloshed ominously.

Slowly, he slid the Johnson propfirst over the stern. There could be no mistakes now. He braced himself to lower the power head onto its clamps. With a final slide, the outboard was on the transom and the small boat reacted to the extra weight and drag, cocking broadside to the wind. He tightened the clamps.

He wiped his face and discovered that perspiration had turned to ice. His hat had a rime of white around it.

He snicked the gear into neutral, pulled the choke button, twisted the throttle to the starting position, and then yanked hard on the starter chord. There was not even an encouraging whuff, or, slight backfire.

Despite all his efforts, his second engine wouldn’t start.

In his T-35 jet trainer, Major Leo Tighe anxiously scanned the surface of wind-churned Superior. It would be almost impossible to pick out a small boat from the white caps. A hit-and-run snowstorm had come up from nowhere, racing with unusual speed out of the west, and dumped 13 inches of snow on the ground.

Cold rain and sleet turning to ice had blanked the Duluth airport and the rest of the Midwest, turning to ice.

He had been lucky to get in the air.

Riding with him in the back seat was Lt. Gerald Buster. Flying in a northsouth search pattern, they were buffeted with strong winds. More than once they came closer to Superior’s outstretched fingers than they cared to.

“There!”

Major Tighe had spotted something in the waves below. He circled.

At 2 p.m., about 20 miles from shore, they saw a small, white boat.

On their first pass, it looked like it was under power. The man in the rear seat of the boat was paying no attention to their low-flying jet.

They circled again, this time lower yet, and, saw that the man’s engine wasn’t putting out any wake, nor was the boat making any progress in the waves. The boat was rolling broadside, or sideways,

to the wave trains — a dangerous position. It looked like the man was in trouble, but he wouldn’t look up or signal to them.

The boat and the man were white — suddenly it dawned on Major Tighe that they were ice covered.

He circled the small craft again and again until a radar station on shore could get a fix on the site and relay the information to the Coast Guard. Low on fuel,

he returned to the Duluth air base. There wasn’t anything else he could do from the air

Silently, he said a small prayer.

All that long afternoon, the skiff drifted with the wind and the waves while the old man labored over his balky engine. The waves were increasing in size, the wind was gusting louder than before, and he was moving further from shore.

A rogue wave reared over the boat, swamping it. His small boat was a quarter full of water. Desperately, he bailed — but his boat was not buoyant enough and riding too low in the water. He moved forward to the bow and laid his hand on his old Lockport.

He felt a twinge of regret wash over him: it had been his fishing partner for many years, and, he’d taken it in to the Hovland blacksmith shop many times to have it

welded up. There was a bond between the old outboard and the Old Man.

With reluctance, he threw it overboard.

The motor hit the water and sank instantly. In the waves, there was not even a ripple where it once had been.

His skiff was lighter now by over a hundred pounds, and, he saw the freeboard lift an inch or two in the bow. He began bailing again, trying to keep pace

with the spray and spume that came aboard. When the water was down to the floorboards, he turned his attention to his one remaining engine.

Somehow, he had to fix his engine. He did not have any tools with him — just an ax. He took off his gloves, baring his skin to the frozen metal, and twisted the gas line off by hand. No gas was coming out — his line had frozen.

There had been too much water in his gas as well.

The old fisherman thought a moment, and then stuck the gas line in his mouth to melt it. He kept it in his mouth, checking from time to time. The raw rubber, soaked in gasoline, made him gag.

After about a half an hour, he blew hard on one end. The ice block popped out. The line was free.

He had been at work on the boat and the outboard all afternoon, and as he looked around him, he saw the short November day was growing dark. He reattached the open gas line to the engine and hauled hard on the starter chord.

With a roar, the old two-cylinder Johnson came to life, and the Old Man headed for a shore he could not see. He knew if he steered into the waves and wind, he’d end up somewhere along the North Shore.

But the oncoming waves were running hard, with seas 20 feet high, dwarfing his boat. The old skiff was taking a terrible pounding. The planks were flexing and they looked like

they were separating. The screws holding them to the frames were pulling out.

There was nothing to do but turn off the engine. The moment the motor stopped pounding, he noticed the awful noise of the sea once more. The wind howled across his open boat, and, the white-crested growlers reared in front of him.

Without power, his boat was cocking sideways to the waves. Breakers were coming in over the side of his boat. Reaching forward, he picked the rope out of the half-frozen slurry in the skiff’s

bilge and tied it to the sturdy wooden fishing crate. He grunted as he hefted the fifty-pound crate over the side. With a splash, it sank part way into the waves,

receding from his drifting boat.

He felt a tug on the rope, and, tied the line off the bow. The boat’s bow swung around to the waves.

His improvised sea anchor was holding, and, his boat was riding to the waves with her bow cocked at a slight angle to them — her best sea-keeping position. But the temperature dropped

further and ice continued to grow on the skiff and the Old Man.

He had done all he could. Now he could only bow his head at the growing fury of the storm.

Back in Hovland, the families were growing desperate. They could look out at the broken seas and imagine the ordeal of their men in the open boats. They shared a sense of helplessness. “What could you do on shore?” Helmer Aakvik’s wife, Christine, wondered aloud.

The sheriff had been called, but snow and high winds kept his floatplane from searching the storm-filled lake. From Grand Marais, the Coast Guard’s small boat came out to search, but it had to turn back when its engine lost power as its gas line began to freeze up.

About 20 miles away near Isle Royale, the steel Coast Guard cutter, Woodrush, got an emergency call. It responded by steaming toward Hovland, into the teeth of the storm.

In the meantime, the Coast Guard sent another, more seaworthy lifeboat plowing its way toward Hovland. When the 36-foot lifeboat arrived at Hovland, it was riding six to eight inches lower in the water because of the ice that had covered the boat. They reported that on their route they had been fighting a Number 6 Sea, whose waves averaged 15 feet in height.

They chopped off the ice, and, started their search up and down the shoreline, trying to estimate where the lost fishermen might have drifted. The lifeboat had no radar and the men had to search for the missing fishermen visually — an almost impossible job in the spray, ice and high waves. By evening, when they called off their search, the wind howled at nearly 50 miles per hour.

The Woodrush kept on station, but temperatures neared the zero mark. The winds were increasing, and, so were the seas. Ice was building on its topsides, making them dangerously heavy, and several times they had to return to harbor to chop it off.

Darkness came early. Along the shore, in the little fishing community, people prayed that the Old Man and the Kid, each huddled alone in their open boats, would survive the night.

He had been out more than sixteen hours and he had nothing to eat or drink. His face was painfully cold, as were his hands. His foot, where the boot had cracked, and water had come in, was growing numb. His mind was growing slack with fatigue.

Waves came like dark walls out of the night. They rose high and crashed into the old boat and he could feel its agony. Spray continuously washed over its bow, and, his boat was icing up.

If ice built up too much, he knew, a small boat will get top heavy and roll over in the waves. Thankful he had taken his hatchet along, the Old Man chopped ice off his boat.

His mind drifted during the long night and he wondered what had happened to The Kid. In his rush to check the nets that morning, he probably just wore his usual work clothes, so he didn’t have oilskins to protect him from the spray. He probably figured he was just going out for a quick dash to the nets and then back again. He didn’t carry a hatchet.

The Old Man thought of Carl with nothing to chop away the ice, and, his boat getting lower in the water as all that spray came aboard and froze.

The Old Man bent his head into the wind. His partner’s end was probably quick, or he prayed it was — Carl probably just slumped down with the cold and the fatigue and went to sleep. In these seas, his boat probably turned sideways and, top heavy with ice, rolled over.

The Old Man dared not sleep. It would be so easy to slump in his little boat, bend his head down to his chest, as if in prayer, and let the motion of the skiff rock him into slumber.

To sleep was to die.

He roused himself. Off in the distance, flashes of light bounced off the headlands of Hovland and Chicago Bay. That would be his rescuers, he thought, but there was no way to tell them that he was further out from shore. A lot further.

His skiff was covered with ice, and, when he looked down, he saw his oilskins were coated in ice. His feet were encased in ice also; even his fingertips had icicles hanging from their tips. The ice encapsulation was what was beginning to keep him warm. It sealed up his oilskins with an extra layer to keep out the surf spray and the wind.

At some time during the night, the moon came out. The Old Man paused to admire the beauty of the spray by moonlight. It glistened white, surreal and ethereal around him.

He also saw something else gleaming white in the water.

Ice had begun to surround his boat.

The light around him brightened, slowly, almost imperceptibly, and the Old Man knew at last his long night was ended. At dawn, the lake was covered with heavy steam — a light gray haze that hid what was below. The Old Man scanned the horizon, but he couldn’t catch a glimpse of the high, dark hills above Hovland — and get a bearing on which way to head home.

But the wind had calmed somewhat. So had the seas.

He waited patiently. When the weak sun began to rise out of the water in the east, he’d have his bearing. He’d swing to the north, and, head home. But his boots had frozen to the bottom of the boat and he found he couldn’t move forward to chop the ice in the front of the skiff. The ice cover had grown: the bow glistened white with ice a foot thick.

Cracking ice chunks off his oilies, he managed to turn to his transom. His outboard was sheeted with ice, and, ice had coated the flywheel. The rope wouldn’t fit in the starting pulley on the motor. The starter rope was frozen hard.

His hands were thick with ice, so he knocked his hands together, and then took off his mitts. Cautiously, he hammered the ice off the outboard, and, with his uncovered hands, he worked a starter rope strand into flexibility. Carefully, he wound two strands around the metal starting pulley. He kept his fingers moving so they would not freeze to the metal. The strands just fit, and, hopefully he put his mitts back on his numb hands. He waited a moment, said a silent prayer, and yanked. The old engine chuffed into life with a puff of blue smoke.The Old Man turned his boat toward shore — and home.

The skiff plowed slowly into the oncoming waves. He found that the bow so heavy with ice that it lifted slowly, and at times, it barely kept buoyancy. The skiff rode eight inches lower in the water because of the ice’s weight.

He managed to keep the engine running for about six hours. His hopes lifted when he was within sight of land, but six or seven miles from shore, the engine stalled and quit.

He checked his fuel supply. Out of gas.

For a moment, he thought he was out of luck, too. His feet were frozen to the floorboards, so he could not stand. He could not reach forward with his ax to chop ice. The boat was full of ice and rode too low in the water.

The Old Man swallowed his pride and turned to his faithful outboard. He loosened the setscrews that held it to the transom, hefted the engine, and, watched as the Johnson slipped overboard. It was now lost forever, but the boat was lighter.

He still had oars but he could not use them. His mitts had stiffened into icy claws. The water was amazingly close to where he sat. It wasn’t gray in color anymore, just a bluish white. Waves moved past, indicating that it wasn’t frozen yet, though chunks of ice surrounded him and bumped into the boat.

He thought about his problem. He could drag the mitts in the water until they thawed, then put them on and carefully fold them around his oars until they froze in place.

Then he could row. The shoreline, he thought, was tantalizingly close.

It was Thanksgiving Day. The Woodrush widened its search, criss-crossing the area, but as the Coast Guard cutter plowed through one bank of fog and into another, its crew grew increasingly worried. The temperature hovered around zero degrees and there was ice in the water. Even if the two men had survived the cold and the ice, the rough lake could have taken down the small boats they were in.

The cutter’s motor grumbled on, its bow parting the waves and ice, while the shivering crew scanned the hungry seas.

“There!” someone yelled.

Above the layer of lake steam, a head had bobbed up, ice-covered and bowed.

His face and beard were glistening with frost, his hat was coated with white, and his oilskin suit was encased in ice and frozen to his boat.

It was the Old Man.

He had not heard them approach. Suddenly, he saw the looming bow of the Coast Guard’s big steel cutter, heading right toward him. He blinked, halfway thinking he was a delusion, until the bow nudged his boat with a bump.

They came over the side in a rope ladder and stood ankle deep in the nearly swamped skiff, lying low in the water. He tried to get up, but he was stiff with cold, and covered with ice from head to toe. He was frozen to his wooden seat. Even his feet had frozen to the floorboards.

With care, they managed to chop him free and lift him out of his skiff. When he was aboard, they fed him hot coffee — his first drink in 29 hours.

They tied a rope around the skiff’s eyebolt and tried to tow it. But the old boat was so heavy with ice, and, so weak after its battle that it only lifted its bow a little, and went under. They had to cut the rope. It sank quickly down into the dark waters.

As they came into harbor, cheering rolled across the waves.

The Old Man looked around, amazed. “There must have been a hundred people there,” he recalled.

Though he was having trouble moving, he still shrugged off offers of help. “I can still walk,” he said. “I’m no cripple.”

He protested when he was placed on a stretcher and given a preliminary examination by a doctor. He did gulp an egg sandwich and drink a pint of hot coffee. The doctor wanted to rush him to the hospital in Two Harbors. “As if I needed a hospital,” the Old Man snorted. “I only froze two toes.”

He declined a helicopter ride to the hospital, insisting on riding sitting up in the ambulance. He was treated for frozen toes and frostbite. His hands were swollen from being exposed. A doctor pronounced him as being in excellent shape, with normal blood pressure. From his hospital bed, he said he knew he’d make it to shore, “even if I had to paddle to Grand Portage.”

Many news people interviewed him and, one asked him if he prayed to his God for help during the long night.

“No,” he said, “there’s some things a man has to do for himself.”

Few words were as sweet to the old man as those of his neighbor, Elmer Jackson. Before Aakvik went out on his long search, he had promised Jackson: “Don’t you worry, the Old Man will be back.”

In the hospital, Elmer Jackson came to the Old Man’s bedside and said, respectfully: “You are a man of your word.”

EPILOGUE

I headed off Hwy. 61 going north and climbed in third gear into the hills overlooking Superior. There it was, a practically unmarked cemetery in the midst of a grassy meadow, surrounded by tall pine trees. The sun was down at a slant in the late afternoon, casting long shadows into the grass — and onto the small granite tombstones.

It was not too hard to find the final resting place of the Old Man, near the pine trees, at the northern edge. Today, a light wind swept through the foliage, gently rustling the pine bows and sweeping onto the clearing with a north woods scent.

His headstone was simple carved granite, recording that he had been born 18 August 1896 and had died 11 January 1987. In the upper left was a ship’s steering wheel, and a small saying had been cared at the bottom of the stone:

Home from the cruel sea and in a peaceful harbor.

I looked at the earth below my feet and I knew what was down there: Helmer was resting at last in a plain wooden coffin, nothing fancy. It was fitted with rope handles and his name had been carved on the coffin lid, along with a compass rose.

He had requested a small addition. Like a proper boat, his coffin had been fitted with a keel.That was so he could, as he put it, “steer a straight course to the stars.”

Helmer Aakvik’s courage to go out in a rising ice storm and his resourcefulness in surviving against great odds is told by

fellow Lake Superior boater Marlin Bree (www.marlinbree.com), in his book Broken Seas: True Tales of Extraordinary Seafaring Adventures

(Marlor Press, $15.95). This award-winning magazine article was excerpted in the The Ensign magazine in its January/February 2007 issue.

TOP

|