| Northwest

Passage Achieved!

By Roger Swanson and Gaynelle

Templin

Our

attempt to transit the Northwest Passage aboard

Cloud Nine in 2005 ended when we were turned back

by pack ice in Franklin Strait. At that time I

felt quite confident in saying “Never again”.

This was my second unsuccessful attempt having

been stopped by ice near Resolute in 1994. Two

disappointments were enough. But I remained in

email contact with Peter Semotiuk, a radio operator

at Cambridge Bay located near the middle of the

Northwest Passage. He commented in one of his

letters that the passage had opened for a time

during the summer of 2006. Early in the year Gaynelle

and I wondered if we should try again. We discussed

the question and decided to wait until June to

review the early ice predictions before making

a final decision. Our

attempt to transit the Northwest Passage aboard

Cloud Nine in 2005 ended when we were turned back

by pack ice in Franklin Strait. At that time I

felt quite confident in saying “Never again”.

This was my second unsuccessful attempt having

been stopped by ice near Resolute in 1994. Two

disappointments were enough. But I remained in

email contact with Peter Semotiuk, a radio operator

at Cambridge Bay located near the middle of the

Northwest Passage. He commented in one of his

letters that the passage had opened for a time

during the summer of 2006. Early in the year Gaynelle

and I wondered if we should try again. We discussed

the question and decided to wait until June to

review the early ice predictions before making

a final decision.

On March 6 Gaynelle and I headed

for Trinidad. With friends as crew we planned

to sail to the Virgin Islands and have the boat

ready to head north if we decided to try for the

passage. Our trip was put on hold when Gaynelle

tripped in a restaurant in Trinidad breaking both

wrists. When the local doctor informed us that

surgery would be required, Gaynelle flew home

with a splint on one arm and an elastic bandage

on the other not realizing at that time that the

second wrist was also broken. After arriving back

in Minnesota, Gaynelle spent four hours in surgery

at Mayo Clinic repairing her right wrist.

While Gaynelle was recovering

at home, I sailed Cloud Nine to the Virgin Islands

so it would be ready to go and then returned to

Minnesota to wait. By June the ice predictions

were cautiously optimistic, Gaynelle’s wrists

were healing, and we decided to go for it. On

June 28 Cloud Nine sailed north from the Virgin

Islands headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia, with

a three day R & R (repair and reconstruction)

stop at Bermuda. Gaynelle was not part of our

crew on this passage because her wrists needed

more healing time.

We

arrived at Halifax and proceeded to the Royal

Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron marina arriving at

0600 on July 12 at Halifax. The RNSYS is the oldest

yacht club in North America being founded in 1837.

The 48 hours preceding our arrival found us sailing

through pea soup fog the entire time. What made

it especially challenging was that our landfall

coincided with the arrival of 135 other sailing

boats completing the Marblehead, Massachusetts

to Halifax race, all of us in fog. It was noon

before we cleared customs, found a mooring, and

had a chance to settle down. We

arrived at Halifax and proceeded to the Royal

Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron marina arriving at

0600 on July 12 at Halifax. The RNSYS is the oldest

yacht club in North America being founded in 1837.

The 48 hours preceding our arrival found us sailing

through pea soup fog the entire time. What made

it especially challenging was that our landfall

coincided with the arrival of 135 other sailing

boats completing the Marblehead, Massachusetts

to Halifax race, all of us in fog. It was noon

before we cleared customs, found a mooring, and

had a chance to settle down.

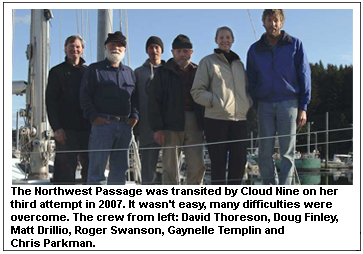

Gaynelle and the rest of our

Arctic crew were waiting for us at Halifax. We

were a crew of six. In addition to Gaynelle and

I we had Doug Finley and Chris Parkman from San

Francisco aboard, both of whom had been with us

on our 2005 attempt. Also aboard were David Thoreson

from Okoboji, Iowa and Matt Drillio from Halifax.

David had been with us on our 1994 attempt and

also on a passage to Antarctica in 1992. Matt

joined us as a replacement for a last minute cancellation.

Gaynelle had been busy prior to our arrival and

her hotel room was filled with enough provisions

to feed six people for 90 days in the Arctic.

After

moving everything aboard and making a few last

minute alterations, Cloud Nine and crew left Halifax

on Gaynelle’s birthday, July 19. Our route

took us northeast along the south coast of Nova

Scotia, and passed through Bras D’or Lake

on Cape Breton Island traveling in fog much of

the time. Bras D’or Lake is about 50 miles

long and is unusual having a lock at the southwest

end and open to the sea to the northeast. Good

weather favored us as we departed the lake and

headed north in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Much

to our surprise, we found ice in the Strait of

Belle Isle between Newfoundland and Labrador.

As we approached Cape Baud on the northeast tip

of Newfoundland, gale force winds overtook us

resulting in a hard night as we worked our way

into St. Anthony, our final stop before heading

to Greenland. After

moving everything aboard and making a few last

minute alterations, Cloud Nine and crew left Halifax

on Gaynelle’s birthday, July 19. Our route

took us northeast along the south coast of Nova

Scotia, and passed through Bras D’or Lake

on Cape Breton Island traveling in fog much of

the time. Bras D’or Lake is about 50 miles

long and is unusual having a lock at the southwest

end and open to the sea to the northeast. Good

weather favored us as we departed the lake and

headed north in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Much

to our surprise, we found ice in the Strait of

Belle Isle between Newfoundland and Labrador.

As we approached Cape Baud on the northeast tip

of Newfoundland, gale force winds overtook us

resulting in a hard night as we worked our way

into St. Anthony, our final stop before heading

to Greenland.

After topping off fuel, water,

and picking up a few fresh provisions we were

ready to go again. Having waited as long as possible

to get the ice outlook before committing ourselves

to the passage, we now needed to keep moving.

Leaving St. Anthony the morning of July 26, we

saw several icebergs and soon ran into fog again.

The large icebergs usually show up on radar, but

the smaller ones and bergy bits do not, requiring

a careful watch in the fog. Starting on an easterly

heading before bending north we hoped to get through

the greater concentration of icebergs floating

south along the coastline carried by the Labrador

current. Although the bergs thinned out the second

day, the wind increased dramatically and we soon

found ourselves running before another gale. Our

only sail was a small jib, but we were moving

fast and making good progress. For several hours

we experienced exceptionally heavy rain, but eventually

the gale blew itself out and conditions improved.

A

day later we were motorsailing due north in clear

calm conditions. One crew member saw a green flash

as the sun went down and we continued under a

full moon in the semi dark Arctic night. Later,

a brilliant display of northern lights made the

evening unforgettable. It is nights like this

that cause us to forget the unpleasant weather

and continue sailing year after year. A

day later we were motorsailing due north in clear

calm conditions. One crew member saw a green flash

as the sun went down and we continued under a

full moon in the semi dark Arctic night. Later,

a brilliant display of northern lights made the

evening unforgettable. It is nights like this

that cause us to forget the unpleasant weather

and continue sailing year after year.

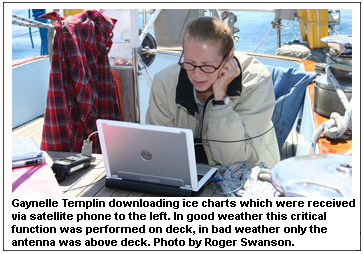

Much of our passage to Greenland

was in fog, often heavy, but the light northerly

wind was not unpleasant. As we progressed north,

we started to experience difficulty with our e-mail.

Our mail comes in via high frequency radio making

it subject to high latitude propagation problems.

This was no surprise because 2007 was expected

to be a bad year for sun spot activity. For this

reason we carried a satellite telephone giving

us backup communication when needed.

On August 1st our headwinds

increased to 25 to 35 knots making for heavy going,

but we had not seen any ice since clearing the

Labrador coast. As we approached Greenland one

incident really got our attention. Gaynelle finished

dinner and went up on deck to relieve the watch

so they could come down and eat. She checked the

radar before going up and found it clear, but

only moments later, a large iceberg suddenly loomed

out of the fog directly ahead of Cloud Nine. Gaynelle

immediately took control from the auto pilot and

narrowly missed the berg. Moments later it disappeared

back into the fog again and careful examination

of the radar revealed no sign of it. This was

a dramatic warning that even large icebergs are

not always visible on radar.

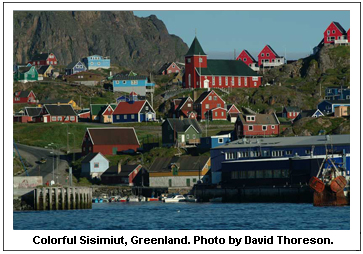

The

next day Cloud Nine crossed the Arctic Circle

at 66 degrees, 33 minutes north latitude formally

entering the realm of the Arctic and the beginning

of the Northwest Passage. The heavy weather with

fog continued and we were taking a lot of water

over the bow. It was cold, in the 30s at night,

and everyone was getting tired from fighting the

constant headwinds and the strain of the continuous

ice watch. Although planning to make our first

Greenland stop at Aasiaat, we decided to divert

to Sisimiut until the weather subsided. Perched

on rocky hillsides just north of the Arctic Circle,

Sisimiut is Greenland’s second largest community

with a population of about 5500. While waiting

for better weather, we had two days to explore

the town. Finally the north wind eased at which

time we were underway again. Encouraging ice reports

influenced us to skip Aasiaat and continue on

to Upernivik, about 350 miles to the north. For

most of this passage our weather was clear and

relatively calm. This was an unparalleled luxury

after the nearly constant fog and often heavy

weather that had accompanied us since leaving

Halifax. The

next day Cloud Nine crossed the Arctic Circle

at 66 degrees, 33 minutes north latitude formally

entering the realm of the Arctic and the beginning

of the Northwest Passage. The heavy weather with

fog continued and we were taking a lot of water

over the bow. It was cold, in the 30s at night,

and everyone was getting tired from fighting the

constant headwinds and the strain of the continuous

ice watch. Although planning to make our first

Greenland stop at Aasiaat, we decided to divert

to Sisimiut until the weather subsided. Perched

on rocky hillsides just north of the Arctic Circle,

Sisimiut is Greenland’s second largest community

with a population of about 5500. While waiting

for better weather, we had two days to explore

the town. Finally the north wind eased at which

time we were underway again. Encouraging ice reports

influenced us to skip Aasiaat and continue on

to Upernivik, about 350 miles to the north. For

most of this passage our weather was clear and

relatively calm. This was an unparalleled luxury

after the nearly constant fog and often heavy

weather that had accompanied us since leaving

Halifax.

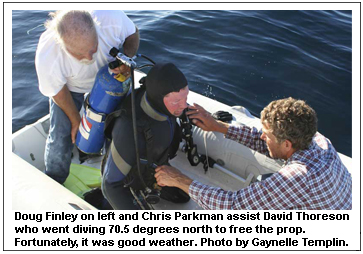

One afternoon at seventy and

one half degrees north latitude and several miles

from the Greenland coast, our engine RPM suddenly

dropped. It acted like a dirty fuel filter, but

that was not our problem. Rope particles in the

water suggested a fouled propeller. This was not

good news at this latitude, but fortunately it

was calm. We dug out our cold weather diving equipment,

put the dinghy in the water, and David volunteered

to go down. He found and cut away a heavy entanglement

of 1/2 inch polypropylene line. It was a relief

to be on our way again without a bent shaft or

other damage while David warmed up sipping hot

drinks.

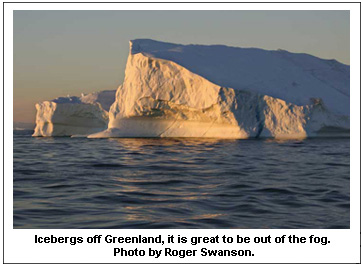

The

weather remained placid, but at times we encountered

many icebergs. On one occasion we counted 79 bergs

all visible at the same time. Motoring through

these magnificent castles of ice is a humbling,

but an indescribably exhilarating experience. The

weather remained placid, but at times we encountered

many icebergs. On one occasion we counted 79 bergs

all visible at the same time. Motoring through

these magnificent castles of ice is a humbling,

but an indescribably exhilarating experience.

On August 6th we moored at Upernavik

and radar repair was our primary concern because

it had failed during our passage from Sisimiut.

Being well past the summer solstice, our 24 hour

daylight was gone. With a few hours of darkness

each night, we needed our radar. Fortunately a

fishing boat in the harbor was able to provide

us with an antenna rotation motor that seemed

to solve our problem.

Shortly after arriving in Upernavik,

another sailing vessel came into the harbor and

moored alongside us. Much to our surprise, it

was Jotun Arctic, the boat with whom we had spent

so much time while marooned by the ice of Franklin

Strait two years age. Not knowing they were in

the area, we could hardly believe this amazing

coincidence as they arrived. Her skipper, Knut,

explained that he was committed to a research

project in Greenland and would not be attempting

the Northwest Passage this year.

Ice reports told us there was

still a large concentration of pack ice in Baffin

Bay between Greenland and Canada, but by going

far enough north, we should be able to maneuver

around it. With fuel and water tanks full, Cloud

Nine was underway from Upernavik on August 8th

in clear weather picking her way through 20 miles

of icebergs and offshore rocks before reaching

open water. The bergs thinned out as we headed

northwest, but heavy fog soon set in lasting nearly

all 400 miles across Baffin Bay. Near the half

way point we encountered the northern edge of

the ice pack but worked around it reaching 74

degrees, 53 minutes north latitude, the northernmost

point of our entire trip.

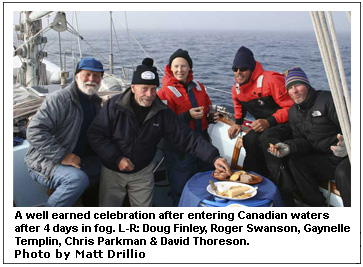

Finally

we were able to bend southwest toward Lancaster

Sound, still in fog. The routine continued with

our watchstanders staring holes in the fog looking

for ice. It was frequently necessary to alter

course to avoid the occasional berg. Fortunately

it was calm most of the time, but temperatures

were in the 30s, cold in the Arctic dampness.

Upon reaching Lancaster Sound on August 11 we

had a party on deck using our fuel drums as cockpit

tables to observe our entry into the Canadian

Arctic. Later in the day the fog cleared and we

saw several white citadels floating nearby not

visible on our radar. We wondered how many we

had unknowingly narrowly missed in the fog. Finally

we were able to bend southwest toward Lancaster

Sound, still in fog. The routine continued with

our watchstanders staring holes in the fog looking

for ice. It was frequently necessary to alter

course to avoid the occasional berg. Fortunately

it was calm most of the time, but temperatures

were in the 30s, cold in the Arctic dampness.

Upon reaching Lancaster Sound on August 11 we

had a party on deck using our fuel drums as cockpit

tables to observe our entry into the Canadian

Arctic. Later in the day the fog cleared and we

saw several white citadels floating nearby not

visible on our radar. We wondered how many we

had unknowingly narrowly missed in the fog.

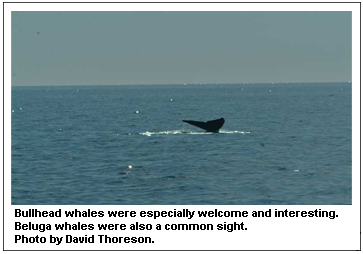

The ice disappeared as we proceeded

west in Lancaster Sound. Our radar failed again,

but the fault seemed unrelated to our previous

antenna problem. It was a glorious clear day as

we continued west in calm waters. Since our ice

reports told us that Franklin Strait was still

closed ahead of us, we decided to take a break

and anchor in Port Leopold on the northeast corner

of Somerset Island. This is a desolate bay and

a lone deserted house on the beach was the only

sign of previous habitation. Port Leopold is the

harbor where James Clark Ross wintered with his

two ships, Enterprise and Investigator, for 11

months during the winter of 1848-49 while searching

for evidence of the John Franklin expedition.

As we entered the bay we found it teeming with

Beluga whales. There must have been well over

a hundred Belugas spouting around the bay. It

was fascinating listening to them as we turned

in for the first good night’s sleep in several

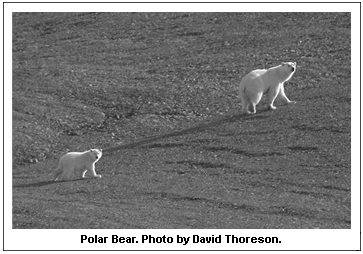

days.The whales were still with us in the morning

and we spotted three polar bears on the beach.

Four of our crew went ashore in the dinghy well

away from the polar bears, but carried our shotgun

just in case. On our trip two years ago, the Canadian

Coast Guard warned us to “Never, never,

never go ashore in the Arctic without a firearm”.

Soon underway, we proceeded west along the north

shore of Somerset Island in ice free water. This

was an almost unbelievable contrast to our '94

and '05 trip where we were completely blocked

by ice in this area for several weeks.

Peel

Sound was also ice free as we headed south. We

chose a route along the east side of the sound

hoping we could see Bellot Strait and Camilla

Cove where we spent so much time in the ice in

'05. We were hand steering much of the time. The

auto pilot’s magnetic compass was not dependable

because of our close proximity to the north magnetic

pole. Our shipboard compasses were also nearly

useless for the same reason. Running blind in

the fog with no visual references, we could only

determine our course by referring to the GPS. Peel

Sound was also ice free as we headed south. We

chose a route along the east side of the sound

hoping we could see Bellot Strait and Camilla

Cove where we spent so much time in the ice in

'05. We were hand steering much of the time. The

auto pilot’s magnetic compass was not dependable

because of our close proximity to the north magnetic

pole. Our shipboard compasses were also nearly

useless for the same reason. Running blind in

the fog with no visual references, we could only

determine our course by referring to the GPS.

On August 15th a brisk following

wind carried us past Bellot Strait and Camilla

Cove, but the fog prevented us from seeing either

location. Ahead lay the Tasmania Islands. Until

two days ago our downloaded ice charts showed

pack ice blocking our passage beyond the islands.

Yesterday’s report showed a lead just starting

to open south of the islands along the east side

of Franklin Strait and Larsen Sound. But would

it stay open? In '05, just 30 miles north of here,

a lead very similar to this one had opened for

us. After starting through with Cloud Nine, it

closed again trapping us for nine days in Camilla

Cove.

As we approached the Tasmania

Islands, the wind eased and the fog cleared which

was a big relief with possible ice ahead. Once

in the lee of the Tasmania Islands we slowed and

waited until midafternoon for the updated daily

ice chart to come in via our satellite telephone.

When it became available, it appeared that the

lead would still be open. With the wind down and

fog free, conditions were ideal for passage. The

word was “Go” and we headed south

with all possible speed. Much to our relief, we

did, in fact, find the lead open. We followed

the eastern edge of Franklin Strait along the

west shore of the Boothia Peninsula and although

we could not see the ice to starboard, we knew

it was close by from our ice information. Pack

ice can only be seen if it is less that three

miles away because it lies low in the water in

contrast to the towering icebergs that can be

seen for many miles.

The next day in Larson Sound

we encountered an 11 mile ribbon of pack ice,

but were able to bypass most of it. Our next concern

was James Ross Strait which is a shallow shoal

and rock strewn area about 20 miles long. Amundsen

went aground in this strait in 1903 and nearly

lost his ship, Gjoa. Without ice and with the

benefit of GPS, we carefully passed through without

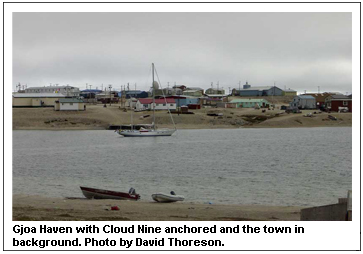

incident and continued on. Morning found us anchored

off the village of Gjoa Haven where Amundsen spent

two winters. It was August 17 and this was a major

milestone for us. I have been trying to get here

for 13 years!

Gjoa Haven is a quiet settlement

of about 1200 people, primarily Inuit. The small

hotel was closed and there were no restaurants,

but two grocery stores were open and seemed to

be the center of most social activity. I suspect

they don’t get many tourists, but everyone

was very friendly and made us feel welcome. Although

there were a handful of automobiles, four wheelers

seemed to be the principal means of local transportation.

We met two individuals who claimed to be direct

descendants of Amundsen; a grandson and a great

granddaughter. We wondered how many cousins they

had!

After spending a second day

in Gjoa Haven, we were underway at 0340 in the

morning of August 19 in light rain headed for

Simpson Strait. This is another passage requiring

careful navigation with many course changes to

avoid shoals. With relatively calm weather and

no threat of ice, all went well despite running

in fog much of the time. Next came Storis Strait

and Requisite Channel also requiring careful piloting,

but all went well. In Requisite Channel we met

and talked with Sir Wilfred Laurier, the Canadian

icebreaker we came to know two years ago. Sir

Wilfred was in the process of setting channel

markers in the narrow straits, but we had already

come through the difficult areas without them.

In Queen Maud Gulf we had to

tack through 20 to 25 knot winds directly on the

nose. We were all pretty tired when we eventually

reached the village of Cambridge Bay on the southeast

corner of Victoria Island. This was another major

milestone for us. We were finally able to meet

Peter Semotiuk who had been such a help to us,

both this year and in '05, relaying ice and weather

information via radio and satellite telephone.

He had good news for us. The new radar we ordered

had arrived in Cambridge Bay and was in the back

of his truck.

Peter had dinner with us aboard Cloud Nine that

evening and we learned he is an electronic technician

working at the North American Warning System installation

at Cambridge Bay. This is part of the updated

and very sophisticated surveillance system that

replaced the old Dew Line that was built in the

late 50’s to guard our northern frontier

during the Cold War. It was interesting to learn

that the Russian Bear is by no means dead and

there is periodic international sparring that

is seldom mentioned in our news.

Cambridge Bay was a little larger

than Gjoa Haven with a population of about 1500

and seemed more active. It apparently gets a few

tourists and occasionally an Arctic icebreaker

cruise ship. Stone carving is an important Inuit

art form and visitors give the artists a chance

to sell their work. In contrast to Gjoa, Cambridge

Bay has an operating hotel and a small gift shop.

A Wall Street Journal reporter was doing an article

on Arctic passages and spent several hours with

us. His article was printed on September 13 and

I was quite surprised to find my picture on the

front page of the WSJ. A friend noted that some

people pay their lawyers a lot of money to try

to keep their pictures OFF the front page of the

WSJ.

Our most important priority

was installing the new radar and we were relieved

to have it working again. Also important were

our first showers since leaving Greenland and

the availability of laundry facilities, much enjoyed

by all! After the usual shipboard maintenance,

plus replenishing fuel, water and a few provisions

we had Cloud Nine ready to go again. It was important

for us to hurry. Although the huge ice pack in

the Beaufort Sea north of Canada and Alaska had

been relatively stationary, several days of strong

northerly winds could move it south and block

our way ending our hopes of completing the passage.

Just before leaving Cambridge

Bay the English sailing vessel, Luck Dragon, arrived

in the harbor. We met her skipper, Jeoffrey, and

his crew briefly in Sisimiut and knew they were

also attempting the Northwest Passage. Their high

frequency radio was not working so they had not

been in contact with either Peter or ourselves,

but they had made good progress after leaving

Greenland a few days behind us.

Our next leg would take us about

600 miles along the south coast of Victoria Island

into the Beaufort Sea to Tuktoyaktuk in the Mackenzie

River delta. Much of the time we were in fog.

We experienced all kinds of weather, most of it

relatively good but were occasionally tacking

into strong winds with waves washing over our

coach roof bouncing us around a bit. Along the

route we saw several old Dew Line surveillance

stations. Peter had explained that some of these

were obsolete and abandoned, but others are active

using sophisticated new technology.

Gaynelle

downloaded an ice chart that showed the pack starting

to move south in Prince of Wales Strait between

Victoria and Banks Islands threatening to cut

off our route, reminding us to keep moving as

fast as possible which is exactly what we were

doing. Gaynelle

downloaded an ice chart that showed the pack starting

to move south in Prince of Wales Strait between

Victoria and Banks Islands threatening to cut

off our route, reminding us to keep moving as

fast as possible which is exactly what we were

doing.

One morning when I got up at

0200 for my watch, I was greeted with a cloudless

sky. It was dark, but the Arctic darkness is not

complete with the pink and red twilight along

the northern horizon. The full moon was visible

low in the southern sky. Because of all the fog

and cloudy weather we had not seen the moon at

any time since the last full moon nearly a month

ago. Varicolored northern lights flickered overhead.

Then a shadow started to appear on the upper left

portion of the moon. To our surprise, it was the

beginning of a total lunar eclipse that started

about 0230 and did not clear until well after

daybreak. I called the rest of the crew and we

were awed by the beauty of this nocturnal display.

Shortly before entering Tuktoyaktuk

on August 29 in the Mackenzie River delta we saw

several whales that we later learned were probably

Bowheads. Tuk was primarily a fuel stop with an

entrance channel over four miles long and only

12 feet deep. It is the major supply port for

the Mackenzie River and western Arctic area. With

the shallow water, supplies are generally transported

by barge. It was a little smaller, but otherwise

similar to the other Arctic settlements we had

seen.

The next morning we set our

clocks back two hours to Alaska time and were

underway toward Point Barrow, now about 500 miles

away. On August 31 we entered Alaskan waters and

discovered that Alaskan waters looked much like

Canadian and Greenlandic waters. FOG! Over our

VHF radio we could hear an Inuit hunting party

asking for assistance in towing a 34 foot whale

ashore. The indigenous Inuit people are allowed

to take a quota of certain whales each year and

this was causing a lot of local excitement.

About midway along the north

coast of Alaska strong easterly winds were predicted.

Easterly winds were good news and they arrived

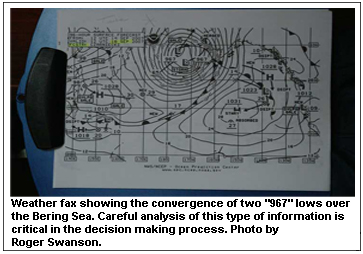

quite rapidly in force at 0400 the morning of

September 1st. The following is a page from my

journal describing our conditions:

“Additional hands were

called on deck to put a second reef in the mainsail.

This was a challenge in the nearly dark Arctic

night with the temperature at 32 degrees and everything

wet from the mist and occasional rain. In order

to perform these operations, we had to work bare

handed in the biting cold. We completed the second

reef and furled the staysail as the weather increased.

With the wind off our stern we needed to wing

the jib to starboard on the spinnaker pole in

order to balance the rig. It is difficult to move

about in our heavy Arctic clothing, particularly

on the pitching foredeck with the boat rolling

and plunging in the heavy seas. We waited for

daybreak for this operation, at which time we

got everything in place and continued on. Wind

continued to increase and twice we reduced headsail

size by rolling in much of the jib. During the

late afternoon we furled the mizzen since it was

disturbing the airflow over the mainsail and also

causing us to round up. We were now averaging

over nine knots under gale force winds carrying

only a double reefed main and a scrap of poled

out jib through the day and into the next night.

We weren’t sleeping very soundly but were

making good time with Point Barrow less than 100

miles ahead.”

The winds held and carried us

past Point Barrow where we jibed and headed southwest

in the Chukchi Sea. The seas were running about

15 feet and occasionally one would wash into the

cockpit giving the crew a cold salt water bath.

With Point Barrow abeam to port and all ice threats

behind us, we all heaved a big sigh of relief.

It was September 2nd and our spirits were high

as the weather moderated and temperatures rose

as we continued south.”

As we passed Icy Cape we recalled

that this was the farthest north point reached

by Captain Cook during his third and last voyage.

From here he proceeded to the Sandwich Islands

(later called Hawaiian Islands) where he was killed

by natives. The Chukchi Sea is very shallow with

most of it being less than 150 feet deep which

was surprising to us.

On September 5 Cloud Nine and

crew, recrossed the Arctic Circle concluding our

transit of the Northwest Passage. This called

for a bottle of champagne to celebrate the occasion.

Our distance from the Arctic Circle going north

to the Arctic Circle going south was 3433 nautical

miles taking 34 days to complete. We knew we still

had a long way to go to reach Kodiak, but right

now we were feeling pretty good. After carefully

reviewing Northwest Passage statistics, as far

as we can determine, Cloud Nine is:

- The first American sailing

boat to complete the passage in one year.

- The first American sailing

boat to complete the passage from east to

west.

- The first boat of any flag

to make the passage east to west this year,

2007.

- At 76, I am probably

the oldest man to attempt this passage.

We didn’t realize that

the hardest part was yet to come.

Our next landmark was Cape Prince

of Wales, the westernmost point of the mainland

continent of North America. It is only 44 miles

across the Bering Strait to Siberia. Looking at

our longitude, it was interesting to note that

we were west of the Hawaiian Islands.

The

next day we arrived in Nome just as headwinds

were starting to increase. The harbormaster had

the latest weather information and told us several

days of gale force southerly winds were predicted.

Since our course to our next destination, Dutch

Harbor on Unalaska Island, was almost 700 miles

due south, we had no reasonable choice but to

wait until the weather improved. The next several

days we listened to the strong winds howling overhead,

but were quite comfortable and secure behind the

large steel pier in Nome harbor. The

next day we arrived in Nome just as headwinds

were starting to increase. The harbormaster had

the latest weather information and told us several

days of gale force southerly winds were predicted.

Since our course to our next destination, Dutch

Harbor on Unalaska Island, was almost 700 miles

due south, we had no reasonable choice but to

wait until the weather improved. The next several

days we listened to the strong winds howling overhead,

but were quite comfortable and secure behind the

large steel pier in Nome harbor.

It was surprising to learn that Nome is experiencing

a new boom period. With gold topping $700 an ounce,

gold mining has become profitable again. Prospectors,

professional and nonprofessional alike, are infected

with gold fever. Hotels are completely sold out

and there is not a room available anywhere in

town. Old run down homes are being renovated and

everything livable is fully occupied.

With time on our hands, we saw

a lot of Nome. The sign said “There’s

No Place Like Nome” and we would agree.

In many ways it resembled a western frontier town

with more saloons than restaurants. Dancing girls

(strippers) from Anchorage were being imported

for weekend entertainment at one of the hotels.

Several homemade gold dredges were in the harbor

hiding from the bad weather outside. They were

rather fragile looking Rube Goldberg creations

but they apparently work well enough to find gold.

With a rented car we drove to the village of Teller,

about 70 miles north of Nome seeing many caribou

and musk oxen grazing along the highway.

Nome history is interesting.

Three Swedes found gold on nearby Anvil Creek

in 1898 and soon the rush was on. By winter the

news had reached the Klondike and by the following

year the tent city that miners originally called

Anvil City had a population of 10,000. The news

soon reached Seattle that gold was being found

on the beaches of Nome with no mountain range

to cross before reaching it. By 1900 the tent

and log cabin city had a population of 20,000

prospectors, gamblers, claim jumpers, saloon keepers

and prostitutes. Included was Wyatt Earp who established

the Dexter Saloon in Nome and is reputed to have

eventually returned to California with $80,000,

a nice nest egg for that day.

We waited in Nome for nine days

while successive low pressure cells moved north

up through the Bering Strait giving us gale force

southerly headwinds. On September 15 another huge

low was approaching, but it appeared we had a

two day window before it arrived. Hopefully this

would allow us to reach the island of Nunivak

about 275 miles south of Nome that afforded good

protection. Knowing that we weren’t going

to get through the Bering Sea without some punishment

we got underway the afternoon of September 15.

The headwinds kept us close

hauled all the way with mist and occasional rain,

but the wind seldom exceeded 25 to 30 knots. We

pushed as hard as possible hoping to make Nunivak

before the next low arrived. Two days later we

were quite happy to drop the anchor in a well

protected cove on the north shore of the Nunivak

Island anchorage just as the headwinds were becoming

strong.

We spent two days waiting at

Nunivak while the large 965 millibar low moved

up through the Bering Sea northwest of us buffeting

the island with strong southerly winds. During

the afternoon of the second day the wind eased

a bit, but another low was forming following on

the heels of the present one. A possible shelter

between Nunivak and Dutch Harbor was St. Paul

Island in the Pribilof Group about 250 miles to

the southwest. It was still blustery, but we got

underway that evening hoping to get as far as

possible toward St. Paul before the next gale

arrived. Once clear of the lee of the island conditions

were pretty tough, but later the next afternoon

the wind eased enough so we were able to make

reasonable progress toward St. Paul Island.

As we approached the island a day later, our surface

analysis and text weather reports indicated we

could expect an exceptionally deep low and would

probably take four or five days to pass. This

was bad news but Gaynelle downloaded other wind

charts where it appeared we were on a ridge between

the two lows. This matched our present conditions

with moderate winds less than 20 knots. Rather

than wait at St. Paul, it looked like we could

head directly for Dutch Harbor staying between

the lows, making it most of the way before the

strong southwesterlies overtook us. If we were

caught before reaching our destination we could

heave to and ride it out at sea.

This

looked like our best alternative and we altered

course for Dutch. That night the wind went light

and the following morning started filling in from

the north. We guessed right. By the time we reached

Unalaska Island the wind had backed to the southwest

and starting to pipe up, but on the morning of

September 24 we were safely moored in Dutch Harbor.

The Bering Sea was finally behind us and we were

quite happy to have bypassed St. Paul Island where

the gale was now really roaring. This

looked like our best alternative and we altered

course for Dutch. That night the wind went light

and the following morning started filling in from

the north. We guessed right. By the time we reached

Unalaska Island the wind had backed to the southwest

and starting to pipe up, but on the morning of

September 24 we were safely moored in Dutch Harbor.

The Bering Sea was finally behind us and we were

quite happy to have bypassed St. Paul Island where

the gale was now really roaring.

Next to us at the dock were

two vessels that are featured in the TV series

The Deadliest Catch about crab fishing in the

Bering Sea, namely Maverick and Far West Leader.

I suspect they were in port for the same reason

as ourselves, to escape the storm conditions outside

the harbor.

The history of Dutch Harbor

goes back to the 1700’s when the Russian

American Company made it their headquarters for

the sea otter fur trade. Their treatment of the

indigenous Aleut population was unbelievably brutal

as they forced them to deliver sea otter furs

to the traders. More recently, Dutch Harbor was

a major base in the Aleutians campaign during

WW II. The harbor was heavily bombed by a major

Japanese carrier task force in 1942. It was supply

port for the recapture of Attu Island in 1943

that resulted in the heaviest casualty rate of

any of the Pacific island campaigns with the exception

of Iwo Jima. Remains of pill boxes, gun emplacements,

and concrete bunkers in and around Dutch Harbor

reminded us of the German fortifications at Normandy.

Dutch Harbor was interesting

but our primary concern was finding a weather

break that would allow us to make the final 600

mile dash to Kodiak Island where Cloud Nine will

spend the winter. The wind had been blowing hard

in the harbor, up to 50 knots, as the low pressure

cell passed north of us. The good news was that

our course would be east northeast and the wind

should be on our backs

When

the wind started to ease, it looked like we might

have another two day window that should get us

at least half way to Kodiak and we could take

shelter in the Shumagin Islands if necessary.

We left the evening of the 25th going through

Unimak Pass into the Gulf of Alaska. The second

night out the barometer started to drop and the

weather deteriorated. For about 36 hours we had

gale force winds including several hours of storm

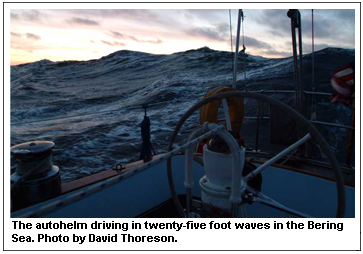

conditions of 55 to 65 with gusts to 70. During

the blow the seas reached 25 feet but fortunately

the wind remained behind us. Our only sail was

a reefed mizzen and a small jib. The downwind

ride was uncomfortable but it was rather exciting

on deck trying to steer the boat down the face

of the waves while trying to avoid a broach or

burying the bow in the short steep waves. In 46

hours the barometer had fallen 32 millibars. When

the wind started to ease, it looked like we might

have another two day window that should get us

at least half way to Kodiak and we could take

shelter in the Shumagin Islands if necessary.

We left the evening of the 25th going through

Unimak Pass into the Gulf of Alaska. The second

night out the barometer started to drop and the

weather deteriorated. For about 36 hours we had

gale force winds including several hours of storm

conditions of 55 to 65 with gusts to 70. During

the blow the seas reached 25 feet but fortunately

the wind remained behind us. Our only sail was

a reefed mizzen and a small jib. The downwind

ride was uncomfortable but it was rather exciting

on deck trying to steer the boat down the face

of the waves while trying to avoid a broach or

burying the bow in the short steep waves. In 46

hours the barometer had fallen 32 millibars.

As we approached Kodiak, the

wind dropped dramatically giving us comfortable

sailing conditions the rest of the way. About

1700 on September 29, Cloud Nine and crew moored

in the Kodiak Marina and our trip was over; 73

days and 6640 miles from Halifax. The total trip

from Cloud Nine’s starting point in Trinidad

on March 17 was 8925 nautical miles or 10,264

statue miles. It was a satisfying feeling to finally

tie up for the last time.

After arriving at Kodiak, we learned the sad news

that the English sailing vessel, Luck Dragon,

had to be abandoned at sea in heavy weather south

of St. Paul Island in the Bering Sea. The crew

was rescued by a fishing vessel and brought to

Dutch Harbor. The sailing boat sank a short time

later.

But for us it had been a good

trip with a good crew and we were all happy to

have finally completed our Northwest Passage transit.

We put Cloud Nine to bed in Kodiak for the winter

and one by one the crew members packed up and

headed home, with Gaynelle and I finally leaving

October 5th.

Roger Swanson is from Dunnell,

Minnesota. He has cruised Antartica twice, the

northwest passage three times and circumnavigated

four times. He has received numerous international

awards for cruising and seamanship. His wife,

Gaynelle Templin, has played increasingly larger

roles on their adventures. She completed her first

circumnavigation in 2006.

David Thoreson has sailed

seven times with Roger Swanson including twice

to the Arctic and over 35,000 nautical miles on

Cloud Nine. He has an interesting blog of the

trip on his website which is his professional

studio at: www.bluewaterstudios.com

For more photos visit the

Celebration Festival Pages in this February 2008 issue.

TOP

|