Playing by the rules

By Dave Perry

| The 2005-2008 edition

of the Racing Rules of

Sailing went into effect

on January 1, 2005. Rules

expert Dave Perry helps

you navigate the rulebook

and previews the

significant changes in

the 2005-2008 rules. |

Watch a crowded windward mark in a

large fleet of boats. As the boats

converge from different directions and

angles, it looks like it will be a

chaotic collision-fest to the

non-sailor. But with the smoothness of a

Broadway dance number, the boats

intertwine within inches of each other

with no contact (usually!), then exit

the mark in an orderly line and head for

the next mark. This is the beauty and

ingenuity of the rules of the sport,

called The Racing Rules of Sailing.

The Racing Rules of Sailing (RRS) are

cleverly crafted and written in clear

plain English to promote the widest

possible knowledge and understanding of

the rules. Everyone who races, whether

skipper or crew, newcomer or seasoned

veteran, should make an effort to learn

the rules. Quite simply, it makes the

game better and safer for all

participants. Sailors who do not know

the rules can ruin the game for others;

sailors who know the rules can best

position themselves to gain a tactical

advantage when boats come together.

I have spent much of my life studying

the rules. I am fortunate that my father

was a real student of the rules. Growing

up, he would quiz me on rules situations

at the dinner table, which I enjoyed.

But you don't need a lifetime to gain a

working knowledge of the racing rules.

Any sailor can learn to navigate the

rulebook and apply the rules to most

situations you'll encounter on the

racecourse. This article will get you

started.

Step one: read the rulebook

|

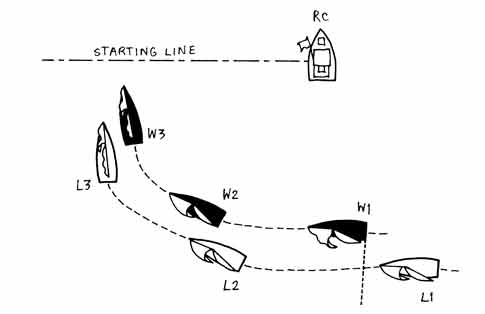

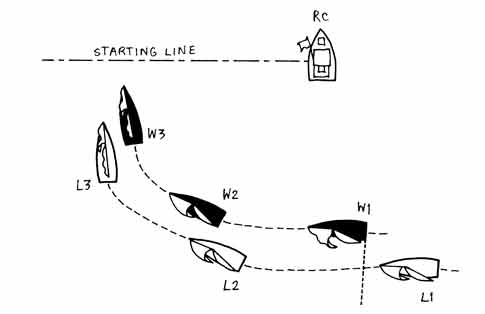

This common pre-start

rules situation

illustrates how the

right-of-way rules (Part

2, Section A) work with

the limitation rules

(Part 2, Section B). It

also demonstrates the

importance of knowing the

terms in Definitions at

the back of the rulebook.

Illustration by Brad

Dellenbaugh, from

Understanding the Racing

Rules of Sailing.

Position 1: L and W are

on the same tack and not

overlapped; therefore L

is required to keep clear

of W under rule 12

(Section A, On the Same

Tack, Not Overlapped).

Throughout the incident

both boats are required

to avoid contact with

each other under rule 14

(Section B, Avoiding

Contact).

Position 2: L and W are

now overlapped; therefore

W is required to keep

clear of L under rule 11

(Section A, On the Same

Tack, Overlapped).

However, L has just

acquired the right of

way, so she must

initially give W room to

keep clear of her under

rule 15 (Section B,

Acquiring Right of Way).

From Position 2 to 3: L

is the right-of-way boat

and W is keeping clear

under rule 11. However, L

is changing course, so

she must give W room to

keep clear of her under

rule 16.1 (Section B,

Changing Course).

Furthermore, because L

became overlapped to

leeward of W from clear

astern, L must not sail

above her proper course

while the boats remain

overlapped under rule

17.1 (Section B, On the

Same Tack; Proper

Course). However, there

is no "proper course"

(defined in Definitions)

before the starting

signal; therefore L can

sail up to head to wind

before the starting

signal. |

The first step to knowing the rules is

to read the rulebook! The Racing Rules

of Sailing is automatically sent to US

SAILING members who register as a racer.

Many clubs and organizations have copies

they will lend, give or sell. The

complete rulebook is also included in my

book Understanding the Racing Rules of

Sailing, which is a thorough explanation

of the rules and their nuances with

extensive quotes from the authoritative

interpretations found in the US SAILING

Appeals and ISAF (International Sailing

Federation) Cases. The rulebook,

Understanding the Racing Rules of

Sailing, and the US SAILING Appeals and

ISAF Cases are all available from US

SAILING (see Resources).

When reading the rulebook, understand

that it has a clear structure. The rules

are divided into seven parts, each with

a distinct subject. At the back of the

book there is a glossary of terms,

entitled Definitions. When these

specifically defined terms are used in a

rule, the term appears in italics. This

further ensures that all who use the

rules will interpret them in the same

way.

The rulebook also includes about 15

appendices that either apply to a

specific type of racing (e.g., match

racing, team racing, radio-controlled

boat racing, etc.) or provide rules or

useful advice on matters such as writing

sailing instructions, hearing protests,

lodging appeals, etc.

When boats meet

The complete rulebook is long, and

sailors should be familiar with all the

rules it contains. But the rules that

apply to situations when boats come

together are covered in one short

section: Part 2, which is only five

pages long! Make it a goal to read

through Part 2 before your next race.

Don't try to memorize every rule. It is

much easier to remember and understand

the rules if you understand their

structure and the structure of Part 2

itself.

The structure of the rules is simple.

When two boats are approaching each

other, the rules give one boat the

"right of way" and the other boat the

obligation to "keep clear" of the

right-of-way boat. The right-of-way boat

has the right to sail the course she is

on without a need to avoid the

keep-clear boat.

For example, when a port-tack boat (P)

is crossing ahead of a starboard-tack

boat (S), S is the "right-of-way" boat

and P is the "keep-clear" boat. If S

does not need to take any action to

avoid hitting P, then P has kept clear;

if S has to change course to avoid

hitting P, then P has not kept clear and

has broken a rule (rule 10, On Opposite

Tacks).

There are essentially four right-of-way

rules, and they are in Section A of Part

2. They are premised on the fact that

there are basically four different

relationships the boats can be in. If

you think in terms of these

relationships, it will be easy to know

which boat has the right of way. The

boats can be either: (1) on opposite

tacks; (2) on the same tack and

overlapped; (3) on the same tack and not

overlapped; or (4) changing tacks.

If they are on opposite tacks, the

starboard-tack boat has the right of way

(rule 10). If they are on the same tack,

they will either be overlapped, in which

case the leeward boat has the right of

way (rule 11, On the Same Tack,

Overlapped); or one will be clearly in

front of the other, in which case the

boat in front has the right of way (rule

12, On the Same Tack, Not Overlapped).

If one of the boats is tacking, it must

keep clear of one that is not (rule 13,

While Tacking).

The rules also place "limitations" on

what boats can do, and these often apply

to the right-of-way boats as well as to

keep-clear boats. An example is rule 14,

Avoiding Contact. Rule 14 tells all

boats to avoid contact with others if

reasonably possible; and it tells

right-of-way boats that if they don't

avoid contact and there is damage, they

can be penalized along with the

keep-clear boat. So if S collides with P

despite being able to avoid doing so and

there is some damage, P will be

penalized for breaking rule 10 and S

will be penalized for breaking rule 14.

There are just four limitation rules and

they are in Section B (General

Limitations) of Part 2.

When boats are about to round or pass

marks or obstructions, there need to be

special rules so the boats will round or

pass in a fair and orderly way. These

are in Section C (At Marks and

Obstructions) of Part 2. There are some

situations where a rule in Section C

might give different rights and

obligations than those in Sections A and

B. When this occurs, the Section C rules

take precedence as long as the boats are

rounding or passing the mark or

obstruction.

Applying the rules

When applying the rules to a situation,

my advice is to ask the three questions

below, in this order. Clearly there are

situations that will require the

application of other rules; but this

model will resolve a large majority of

situations.

(1) What was the relationship between

the two boats, which will determine

which boat had the right of way (Part 2,

Section A); did the keep-clear boat keep

clear?

(2) Did either boat have any limits on

it imposed by a rule in Section B; and

if so, did it comply?

(3) Where were the boats on the

racecourse? For instance, if they were

about to round or pass a mark or

obstruction, then look in Section C to

see what rules may apply.

Remember that different rules can apply

as a situation develops on the water, as

you'll see in the diagram.

Applying the rules to situations, either

actual or hypothetical, will help you

gain confidence in your rules knowledge.

To expand your knowledge further, attend

rules seminars run by clubs and class

associations. Ask judges at regattas

about rules situations that may arise.

To understand procedural rules for

running races and hearing protests,

volunteer to help run races and sit in

on protests. Your rules knowledge will

rapidly expand-which will make you not

only a better racer but also more

qualified to run races and hear

protests, all to the benefit of the

sport.

Significant rule

changes for 2005-2008*

Here is a quick overview

of the significant

changes in the 2005-2008

edition of The Racing

Rules of Sailing (RRS),

from the 2001-2004 RRS.

These brief summaries are

not intended to be actual

representations of the

rules, nor is this a

complete list of all the

changes in the 2005-2008

RRS.

• Preamble to Part 2

(When Boats Meet): The

preamble now clarifies

that when a racing boat

meets a boat having no

intention of racing, the

racing boat is required

to comply with the

International Regulations

for Preventing Collisions

at Sea (IRPCAS) or

government right-of-way

rules, or risk

disqualification.

However, only the race or

protest committee can

protest the racing boat.

• Rule 16.2 (Changing

Course): This rule now

applies only when a

port-tack boat (P) is

keeping clear by passing

astern of a

starboard-tack boat (S).

If P is crossing ahead of

S (upwind or downwind), S

may change course and

make P immediately change

course to continue

keeping clear, provided P

can do so in a seamanlike

way.

• Rule 19.1 (Room to Tack

at an Obstruction): Now,

a boat that hails for

room to tack when it does

not need to make a

substantial course change

to safely avoid the

obstruction breaks rule

19.1. The boat being

hailed must still respond

to the hail, but she now

has a rule she can

protest under when she

thinks the hail was

unfounded.

• Rule 31.2 (Touching a

Mark) & Rule 44.2

(Penalties for Breaking

Rules of Part 2): Once a

boat that has touched a

mark has done one turn

that includes a tack and

a gybe (in either order),

it may continue in the

race; i.e., it does not

need to do a complete

360-degree turn. The same

is true with the second

turn of a boat doing two

penalty turns for

breaking a Part 2 rule;

it no longer needs to do

a complete 720-degree

turn.

• Rule 40.2 (Personal

Buoyancy; Harness): As of

January 1, 2006, trapeze

and hiking harnesses must

have a device that allows

competitors to quickly

release themselves from

the boat at any time

while in use.

• Rule 42 (Propulsion):

"Sculling" has been

redefined as any repeated

"forceful" movement of

the helm, regardless of

its effect. Furthermore,

any repeated helm

movement that propels the

boat forward is also

sculling. Sculling is now

permitted when a boat is

above close-hauled and

has little steerageway

and is trying to turn

back down to

close-hauled.

• Rule 61.1(a)(3)

(Protest Requirements):

In an incident in which

it is obvious to the

boats involved that there

was damage or injury, the

boats involved do not

need to say "Protest" or

fly a protest flag to

protest; they simply have

to inform the other of

their intent to protest

within the time limit for

lodging a protest.

• Rule 62.1(a) (Redress):

The actions of the

organizing authority can

now be the subject of a

redress request.

• Appendix F (Appeals

Procedures): All appeals

of protest committee

decisions in the U.S. are

now to be sent directly

to US SAILING, which in

turn will forward them to

the appropriate

association appeals

committee.

*Excerpted from

Understanding the Racing

Rules of Sailing Through

2008 by Dave Perry,

available from US SAILING

(www.ussailing.org/merchandise). |

Reprinted with permission from US

SAILING, the Newsletter, a publication

for the members of US SAILING.

Resources:

www.ussailing.org/rules

To order copies of the

rulebook, Dave Perry's

Understanding the Racing

Rules of Sailing, and

other books on rules,

visit

www.ussailing.org/merchandise |