|

Reach the World - Chicago

Bringing the World into

Classrooms

“Wait…those

coordinates put you…in the middle of the Red Sea?”

she radioed in the bewildered tone of a confused

calculus student at the chalkboard.

Deadpanning, Aaron

replied, “Wait. Let me check… yes…we do appear to be

in the middle of the Red Sea.”

“I’m not sure whether

to admire you boys, or pity you,” the leader of the

single-sideband (SSB) cruisers’ radio net playfully

jabbed.

Each of the 15 other

boats in the morning radio net had called in from

the comfort of a protected bay along the Sudanese or

Egyptian coast. They were waiting out the 25 knots

of northeast breeze and accompanying short choppy

waves, characteristic of the Northern Red Sea in

late spring. Each of the 15 other

boats in the morning radio net had called in from

the comfort of a protected bay along the Sudanese or

Egyptian coast. They were waiting out the 25 knots

of northeast breeze and accompanying short choppy

waves, characteristic of the Northern Red Sea in

late spring.

Forty miles west of

Saudi Arabia, we were beating north toward the Gulf

of Suez, and making good time given the conditions.

Ever mindful not to

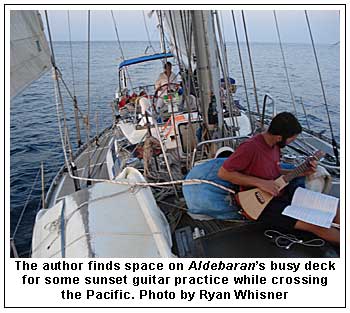

appear brash, Aaron explained that Aldebaran, our

1976 Swan 431, with her seven foot fin keel,

overbuilt glass hull, and 16mm rigging, is a race

horse to weather. Plus, one of the luxuries of

having five people on board is the ability to

hand-steer tough passages and still get some sleep.

Sixteen thousand sea miles behind us, we had little

left to prove. We did, however, have a schedule to

keep.

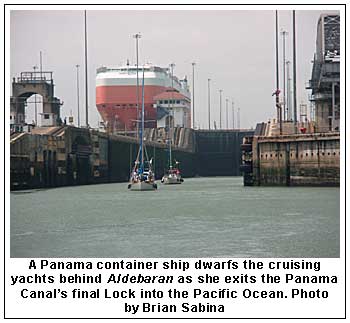

Aldebaran and her

crew were anything but the typical round-the-world

cruising boat. Most circumnavigations are Mom and

Pop operations. Having bought a boat and prepared

for years, couples put their lives on hold and chase

four to seven years worth of sunsets west.

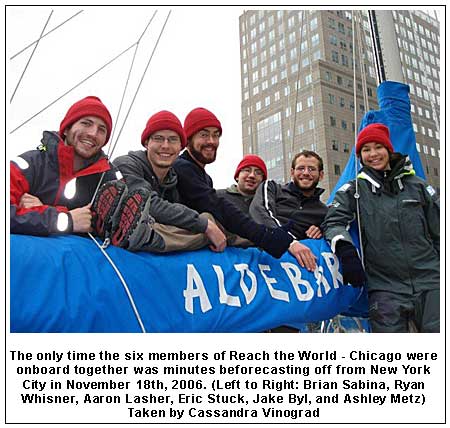

We

were six twenty-somethings, one year out of college,

trying to make it around in two years. Imagine the

Doogie Howsers of the cruising circuit. We bought

Aldebaran on a loan split six ways, and spent three

intense months massaging out the major problems

before casting off in November of 2006. With minimal

prior blue-water experience, we rabidly asked

questions, got lots of help, and learned quickly.

Three months in, our above standard safety measures

and seamanship were matters of personal pride. around in two years. Imagine the

Doogie Howsers of the cruising circuit. We bought

Aldebaran on a loan split six ways, and spent three

intense months massaging out the major problems

before casting off in November of 2006. With minimal

prior blue-water experience, we rabidly asked

questions, got lots of help, and learned quickly.

Three months in, our above standard safety measures

and seamanship were matters of personal pride.

Following the

standard route, known as the Coconut Milk Run, we

sailed (generally) east to west downwind across the

little latitudes and through both canals.

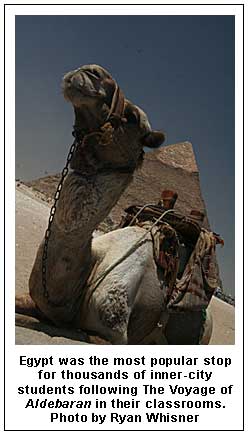

The biggest

difference between us and other cruisers was the

purpose of our journey. Each week, 4,000 inner-city

students from Chicago and New York City Public

Schools laughed, imagined, and learned about far off

cultures and environments through our crew. Their

classrooms followed The Voyage of Aldebaran online

as part of the educational programs of Reach the

World (www.reachtheworld.org).

“How did y’all get

involved with Reach the World, and can I go next

year?” asked Darrel, a third grader from Henderson

Elementary on Chicago’s Southside during a classroom

visit this past June. (We personally visit all of

our partner classrooms in Chicago at the beginning

and end of each school year.)

“Wow, great

question!” I laughed, slightly surprised. “That’s a

sixth grader question!” Darrel beamed. In truth,

it’s a question we got from people of all ages.

In the spring of

2004, the six of us (Aaron, Ashley, Eric, Jake, Ryan

and Brian) were juniors on the Northwestern sailing

team. We decided we wanted to do something special

when we graduated. We wanted to sail around the

world, but we wanted to do it in a way that also

made a difference.

A year later, after some trial and error, we founded

Reach the World - Chicago, the first branch of a New

York City b ased non-profit called Reach the World.

Reach the World’s mission is to integrate exciting

social studies and science material into

under-resourced elementary and middle school

classrooms, broadening students’ worldviews and

helping them learn with technology. In Chicago, we

achieved this goal by linking students to The Voyage

of Aldebaran. ased non-profit called Reach the World.

Reach the World’s mission is to integrate exciting

social studies and science material into

under-resourced elementary and middle school

classrooms, broadening students’ worldviews and

helping them learn with technology. In Chicago, we

achieved this goal by linking students to The Voyage

of Aldebaran.

Planning and

executing our trip through Reach the World

fundamentally changed our experience. For one, at no

point in the journey were all six of us on

Aldebaran. At least one person was always in Chicago

running the company. During summer break, four

people flew home to visit classrooms and fundraise.

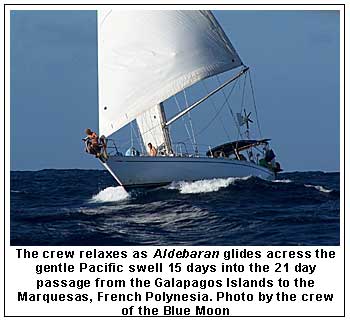

We planned our route

not only around storms, winds, and currents, but

also the collective attention spans of 7-12 year

olds. Kids bore quickly. We could at most squeeze

three weeks of content out of one location. Usually

we only stayed in places ten to fourteen days. If

most cruisers moved at a 10 minute-a-mile pace, we

were on track to qualify for the Boston Marathon. We

traded palm-lined sandy beaches and idyllic

anchorages for ports with fast internet, good

transportation, and lots to write about.

It’s true that

sailing around the world is an exercise in fixing

your boat in exotic locations. The adage doesn’t

mention all of the hours spent walking from one

small store to the next trying to locate the right

part in your best broken native tongue. I now know

“stainless steel” in six different languages.

Each week our

crewmembers were also responsible for researching

and writing educational articles for the Reach the

World website, answering student emails, collecting

data for classroom research projects, and

video-conferencing with students back in the States.

The personal connection developed between the

students and our crew was tremendous. It’s what

separated our program from being just another

website or text book. It’s what got kids excited

about learning.

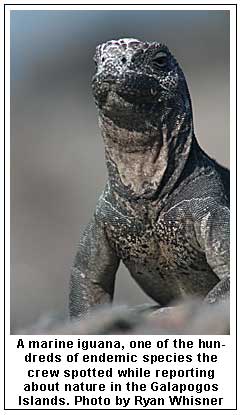

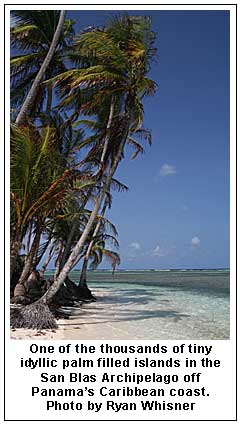

Our “jobs” (we are

unpaid volunteers) as field researchers led us into

some incredible adventures: seeing wild tigers on a

safari in India, staying in a Kuna Indian home in

the San Blas Islands of Panama, interviewing a CEO

in Dubai, visiting local schools in Ecuador,

swimming with sea lions, sharks, and penguins in the

Galapagos islands, helping out in an orphanage in

Africa, getting haircuts and shaves from displaced

Iraqi barbers in Yemen, and being taught how to make

authentic food in Thailand, to name a few. We were

always pushing to do more. Other cruisers arrived

into ports, we took them by storm. Our “jobs” (we are

unpaid volunteers) as field researchers led us into

some incredible adventures: seeing wild tigers on a

safari in India, staying in a Kuna Indian home in

the San Blas Islands of Panama, interviewing a CEO

in Dubai, visiting local schools in Ecuador,

swimming with sea lions, sharks, and penguins in the

Galapagos islands, helping out in an orphanage in

Africa, getting haircuts and shaves from displaced

Iraqi barbers in Yemen, and being taught how to make

authentic food in Thailand, to name a few. We were

always pushing to do more. Other cruisers arrived

into ports, we took them by storm.

“Lots of people told

us we were crazy,” I explained to Darrell, “but we

had a dream. We didn’t pay any attention to them. We

listen to each other, and worked hard. And yes, you

can join Reach the World, but first you have to

graduate college!”

“How far away from land do you think we are?” asked

Jake, lazily using his foot to steer the boat over

following seas during a sunset cockpit dinner. We

were five days into an 11 day passage from Thailand

to Sri Lanka. This was the type of question that

spurred wonderful humorously heated debates.

Before anyone could

conjecture, Ryan’s eyes bulged and finger shot up.

Laughing, he choked down the piece of seared fresh

yellow-fin tuna in his mouth. “About a mile…

straight down,” he said. We laughed and moved onto

one of the thousands of other seemingly mundane

topics that kept us occupied for days.

As the sun darted

below the horizon in typical tropical fashion, we

attentively watched for a green flash; we were not

to be rewarded.

“Rule 28,” said

Aaron. We all knew what it meant. Rule 28: night

time is life time - time to put on life jackets and

clip in. We had started developing rules a year

earlier to memorialize key lessons learned. We

assigned them random numbers. Rule 28 was, in fact,

the first rule instated. We all knew a handful by

heart, 43: raise your sail in the lee, 76: have a

good electric drill, etc. Rule 28 sent Eric and Ryan

below. They handed up life jackets. We handed dirty

plates and bowls down.

Aaron and I clipped

into the jack lines and headed forward to drop in a

reef in the main, raise the staysail, and roll in a

bit of genoa: our stable heavy air set up. Better to

sacrifice some speed and put the reefs in while

everyone is awake than be overpowered in the middle

of the night and have to call an extra person up on

deck. As I dropped the halyard and winched in the

reefing line, I remembered a time, having grown up

racing but never cruising, when this would have

seemed preposterous. Things had changed. I now

understood why one avoids upwind passages when at

all possible. Aaron and I clipped

into the jack lines and headed forward to drop in a

reef in the main, raise the staysail, and roll in a

bit of genoa: our stable heavy air set up. Better to

sacrifice some speed and put the reefs in while

everyone is awake than be overpowered in the middle

of the night and have to call an extra person up on

deck. As I dropped the halyard and winched in the

reefing line, I remembered a time, having grown up

racing but never cruising, when this would have

seemed preposterous. Things had changed. I now

understood why one avoids upwind passages when at

all possible.

My watch beeped:

eight o’clock, time to drive. (A good Timex Ironman

watch, headlamp, and polarized sunglasses are the

pantheon of personal effects to bring on an extended

cruise.) Jake relayed the vitals - average speed

over ground, wind patterns, impending changes of

course, like a doctor passing off charts at the end

of a shift. He handed me the wheel, and headed below

to fill out his log.

It was still two

hours until moonrise. The water was dark, the stars

bright. We’d been in following seas and 15-20 knots

of breeze for a couple of days. I steered the boat

by rote, listening to the wash of salty foam hitting

our quarter, occasionally glancing at the pedestal

compass. I thought about life and people at home. our quarter, occasionally glancing at the pedestal

compass. I thought about life and people at home.

“Ryan?” I called out looking at the orange-tinged

night sky through the window of my new bedroom in

Chicago.

“What’s wrong?” he

answered back from across the house.

“I just realized this

is the first time I’ve slept alone in a room in nine

months. It just feels weird.”

“Goodnight buddy,” he

said in a tone that let me know he understood.

Sailing around the

world before starting your adult life has only one

significant downside. You have to come back and

start your adult life. Entering back into the normal

world surfaced a lot of unexpected feelings.

Hundreds of little things were odd. There were a lot

of adjustments to make.

I had forgotten about

long summer days. In the tropics there are 12 hours

of daylight. It gets dark by 6:30 every evening, and

there is very little twilight. Direct sunshine at 8

PM was downright confusing my first day back.

I was always cold. A

couple hundred days of sunny 85-90 degree weather

thins out your blood. I felt like a flower struck by

a late spring freeze. I carried a jacket with me all

June. Air conditioned houses were hell.

Chicago streets

seemed abnormally wide, and equally abnormally

quiet. Apparently the higher a country’s per capita

GDP, the less its drivers lay on the horn.

The inside jokes of a

tight knit crew were replaced by the perpetual

questions, “did you see any big waves or bad

storms?” and “what was your favorite place?” The inside jokes of a

tight knit crew were replaced by the perpetual

questions, “did you see any big waves or bad

storms?” and “what was your favorite place?”

After two months of

being back, my golden tan has started to fade and my

blood has thickened. Not much seems odd any more.

I’m no longer introduced as “Brian, who just sailed

around the world.” I’ve even gotten used to fresh

water spray again.

One thing that hasn’t faded is the quiet confidence

of being an around-the-world sailor. It never will.

Neither will the memories and kinship between our

crew, and most importantly, our desire to do it

again.

Even though The

Voyage of Aldebaran is over, Reach the World -

Chicago will continue to expand the horizons of

Chicago’s important young minds. Next year thousands

of underserved student’s will follow the RTW-C’s

Bike Africa Expedition as it pedals 7,500 miles from

Cape Town, South Africa, to Cairo, Egypt. If you

would like to support Reach the World, please see

the ad for the BIG TEAM REGATTA on page 45, or call

Brian Sabina at 773-698-6900. If you are inspired to

take a trip of your own, Aldebaran is currently on

the market in Mallorca, Spain. If you are interested

in learning more email aaron@reachtheworld.org.

Delivery can be worked out.

TOP

|