Into the Ice

Return to the Northwest Passage

by Roger B. Swanson

Not having seen polar bears in this northern area, we felt comfortable taking walks ashore usually accompanied by the crew of Jotun Arctic and their three dogs. By climbing hills overlooking Bellot Strait we could see through most of its length and it appeared to be nearly ice free which was encouraging. Ice reports finally showed a lead starting to open along the east edge of Franklin Strait and Larson Sound and the passages farther south in James Ross Strait and further west were open.

Two boats coming from the west, Idlewild and Fine Tolerance had been waiting for

some time in Cambridge Bay to complete their Northwest Passage from west to

east. As we waited in Fort Ross, they left Cambridge Bay and moved east past

Gjoa Haven and turned north through James Ross Strait. They were making

excellent progress. It appeared that if we could get through the next 100 miles,

we should have clear sailing all the way to Point Barrow. Another day passed and

the lead continued to open. Bellot Strait appeared to be clear. This is what we

had been waiting for. It was time to go!

Sept 2: Cloud Nine and Jotun Arctic were underway at

last, comfortably passing Magpie Rock on a favorable tidal current. The passage

through Bellot Strait went well, but we found ice had collected near the west

end of the strait. After working through this concentration both of us continued

south together in Franklin Strait about 15 miles in 2 or 3/10 pack making good

progress. Toward evening we needed to find a place to anchor because we were now

experiencing several hours of darkness each night and did not want to be out in

the pack after dark. We found a spot along the shore that was reasonably

sheltered from the southerly wind and anchored for the night. After getting

settled, ice moved in around the boat making it necessary to constantly push

with our long boathooks against the ice floes to try to keep them away from our

hull, particularly around the stern where they threatened our rudder. The

constantly moving ice forced us to reanchor during the night.

|

| Cloud Nine trying to gain a few more yards through the ice. |

Sept 3: In the morning we watched a polar bear swim completely around

Cloud Nine very close alongside looking us over. He then swam over to

Jotun Arctic and looked like he might try to climb his stern ladder until

Knut shot down into the water between the bear and the boat. The sudden sound

and the water in his face discouraged him after which he effortlessly jumped

onto an ice floe and wandered out to sea on the pack ice. I don’t believe a bear

could climb aboard Cloud Nine from the water with our high freeboard, but

if we had ice alongside, it would be no problem for him to jump onto our deck.

For this reason we kept a careful watch for the guys in the white suits!

After moving to a slightly better location, we spent the day waiting and hoping

the ice would thin out so we could proceed, but it wasn’t happening. The ice

around us was a constant threat requiring frequent pole work and periodic

reanchoring. Farther offshore we could see nothing but 8 to 9/10 pack ice.

Sept 4: By morning we realized that the lead along the east side of Franklin

Strait that had opened a few days ago encouraging us to proceed had now closed.

We were trapped! The two boats coming from the south, Idlewild and

Fine Tolerance, were in even more serious trouble. They had gone into the

pack and were now beset in 8 to 9/10 ice. They were drifting north with the

current in Franklin Strait toward the Tasmania Islands and no longer in control

of their destiny. All four boats were in radio contact with each other and with

Peter. The outlook was not good for any of us, but the two boats stranded in the

pack were in serious danger of being crushed by the ice.

At this point there was no longer any question of trying to continue on, it was

now a question of how to escape. More ice was moving into our anchorage

completely surrounding us much of the time. It was relatively calm, but a

contrary wind would bring the pack in on us and the increased ice pressure would

drive us ashore. We desperately needed better shelter.

Knut pulled his dinghy over the ice to some open water and sounded a small bay

near our anchorage that we first thought too shallow to enter. To our surprise,

he found 12 feet at the entrance and 25 feet inside which should give us good

protection. Later that afternoon the ice moved enough to allow us to proceed

into the small bay and anchor. Once inside we had much better shelter being

protected from wind and ice pressure caused by the heavy pack outside the

harbor. We had a more relaxed night, but the thin film of new ice on the surface

of the water in the morning kept us from relaxing too much.

|

| At times our cove had enough ice that we could almost walk ashore. |

Sept 5-6: The next two days brought little change in ice conditions for us.

Our hideaway cove was relatively comfortable but we desperately needed an

easterly wind to open a lead offshore and allow us to escape. One day was spent

filling our water tanks from a stream ashore using jerry cans. It took most of

the day, but helped pass the time. The situation for the two boats offshore was

much more critical.

Idlewild with its crew of six had been completely forced out of the water by

the closing ice. She was heeled over, but riding high and dry on an ice floe out

in the pack. Fine Tolerance was getting bashed about so badly that the

two crew members aboard felt she might be crushed and sink. Idlewild

looked marginally safer on top of the ice. At this point the Fine Tolerance

crew abandoned their boat and made their way from ice floe to ice floe across

the quarter mile of pack ice separating them from Idlewild. Both boats

were drifting with the pack toward the Tasmania Islands and were in danger of

being crushed or driven ashore when the ice pack started squeezing together to

pass between the islands. To my knowledge they were never called, but the

Canadian Coast Guard was aware of the problem and sent an icebreaker from Gjoa

Haven to assist.

|

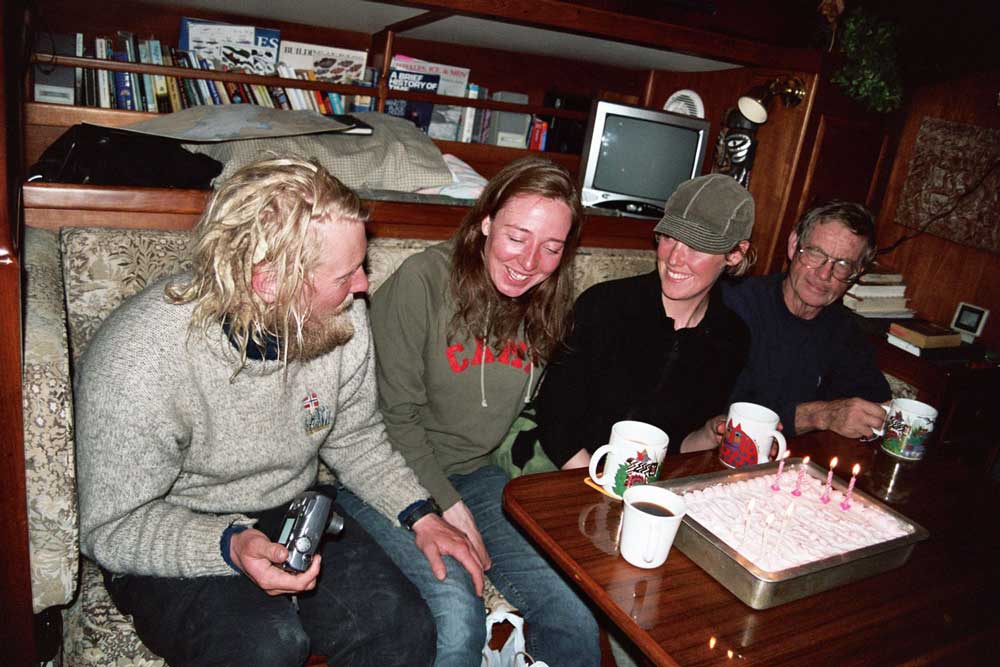

| September 7th was Camilla’s birthday - on left is Knut, captain of Jotun Arctic. |

Sept 7: The ice pack was still drifting north in Franklin Strait but

Idlewild and the abandoned Fine Tolerance were now separated by about

6 miles because they had taken different routes through the Tasmania Islands.

Both crews are still aboard Idlewild on top of the ice. Our situation had

not changed. Ice moved in and out of our cove with the tide, but we were not

under pressure from the pack outside.

It was Knut’s wife, Camilla’s birthday today so Gaynelle baked a cake and we had

a birthday party aboard Cloud Nine to celebrate. Since our little harbor

does not even exist on the charts, we decided to name it Camilla Cove. It was

sometimes possible to walk between Cloud Nine and Jotun Arctic

when the ice surrounded the boats.

Sept 8: The Coast Guard icebreaker Sir Wilfred Laurier reached

Idlewild and spent most of the day getting her off the ice floe and back

into the water. She then tried to follow the icebreaker out to an area of less

concentration. Because large chunks of ice immediately filled in behind Sir

Wilfred Laurier, the only way Idlewild could follow was to press her bow

hard against a cushion hung over the stern of the larger ship as they slowly

moved forward. Although her bow area was bent up pretty badly doing this, they

did reach thinner ice where Idlewild could maneuver unassisted. The crew

of Fine Tolerance had now moved aboard the ice breaker. During this time

the current in the ice pack reversed and the abandoned Fine Tolerance was

starting to drift back south again.

By this time, the rescue operation in Franklin Strait was less than 15 miles

south of us in Camilla Cove. As darkness fell, the presence of the icebreaker

nearby was somewhat reassuring, but we had no way of knowing if they could help

us because they could not get into our shallow anchorage and we didn’t know if

we could get out. It was cold in Camilla Cove and it snowed overnight.

Sept 9: With the arrival of daylight, the icebreaker left Idlewild in

the relatively open pack and went back to recover Fine Tolerance who was

now out of sight. When they found her they discovered she was damaged and could

not run under her own power so they took her in tow and headed back north again.

By the end of the day, Sir Wilfred Laurier, with Fine Tolerance in

tow and Idlewild nearby, were hove to about three miles southwest of

Camilla Cove. The plan was to try to get us out of our anchorage in the morning

and then all proceed north to Bellot Strait and on to Fort Ross tomorrow. The

problem was how to get through the half mile of 8 to 9/10 pack ice completely

enclosing Camilla Cove.

|

| As Sir Wilfred Laurier started to back slowly we followed in her path. |

Sept 10: After spending six anxious days in Camilla Cove, Jotun Arctic

and Cloud Nine got underway at 0430 and managed to work out of our tiny

harbor into the heavy pack outside. Another five hours of hard work only gained

a few hundred yards at which time we were completely beset. Fortunately we

succeeded in reaching deeper water, 50 or 60 feet, which was critical. Sir

Wilfred Laurier had cast Fine Tolerance adrift again and was slowly

moving toward us. Progress came to a sudden halt when Sir Wilfred Laurier

grounded on a bar about a half mile from our location.

She was able to back free after which she put two small boats in the water. They

carefully sounded the bar area finding a spot where she could cross the shoal.

With a crewman using an old fashioned lead line sounding directly from her bow,

Sir Wilfred Laurier moved very slowly and carefully toward us until her bow

almost touched Jotun Arctic. She then started backing allowing Jotun Arctic and

Cloud Nine to follow in the space she left open. As expected, the ice

immediately started to close the channel left by the icebreaker, but she backed

very slowly and we were able to push our way through until we reached the

relatively open pack outside. It was a relief to be clear of Camilla Cove! It

had been our protection from the pack outside, but could have become our prison

for the winter.

It was now past noon. We, along with Jotun Arctic, rafted up to

Idlewild in the broken pack while the icebreaker went back to recover Fine

Tolerance. Our new problem was a 40 knot northwesterly gale that was forecast

for tonight and tomorrow that would undoubtedly close the pack along our shore.

The icebreaker recommended that we head south about 20 miles to Wrottesley Inlet

where we could probably find shelter until the gale passed over. This was the

opposite direction from where we wanted to go, but there was no choice. Sir

Wilfred Laurier with Fine Tolerance in tow, and the three of us

following in her wake, headed south in 1 to 5/10 ice toward Wrottesley Inlet.

When we reached the inlet the icebreaker hove to in deeper water with Fine

Tolerance in tow while we three small crafts moved ahead to look for an

anchorage. A problem developed because what we expected to be a gradual sloping

bottom was over 400 feet deep. It was extremely dark with strong wind and

swirling snow as we pressed on looking for a place to anchor. A deep fjord ran

inland from the head of the bay that we followed for several miles. It was

nearly midnight when we finally found a small shallow area where Cloud Nine

and Jotun Arctic were able to anchor while Idlewild found

another spot about 5 miles farther up the channel. Relief for the moment, but

what next!

|

| Our first icebound anchorage outside Camilla Cove. |

Sept 11: We made it through the blustery night. The anchor watch recorded

our GPS position every 15 minutes to alert us of a possible dragging anchor. In

the morning we found ourselves in a narrow channel less than a half mile wide

with steep rocky snow covered banks on both sides. Between snow squalls we could

see it was incredibly beautiful, but what a wilderness! A herd of muskoxen

ranging on the steep banks suggested the name Muskox Inlet for our anchorage.

The deck was covered with 3 inches of snow that we worked to remove. It was also

necessary to clean up our lines as much as possible to avoid them becoming

encrusted with ice. Sir Wilfred Laurier informed us that as expected the

northwest gale had closed the lead between us and Bellot Strait. Once again

there was nothing to do but wait and hope for a change in the weather.

Sept 12: After another cold windy night with several inches of snow, the

wind eased and the weather report was a little better. That afternoon, at the

invitation of the icebreaker captain, the three small crafts proceeded to where

Sir Wilfred Laurier was lying to in Wrottesley Inlet and rafted

alongside. They graciously offered us showers and dinner which we happily

accepted. Socializing with the icebreaker crew was pleasant and informative.

Captain Mark Taylor explained that he hoped in the next day or two we could

proceed back to Bellot Strait and Fort Ross. Once we got to Fort Ross we would

be able to proceed independently as Prince Regent Inlet on the other side was

open. However, at the moment the outlook for tomorrow was not bright because the

ice charts were still showing 9/10 ice between here and Bellot Strait. Two

icebreakers were now standing by, the second being Canada’s largest icebreaker,

Louis S. Laurent, who just arrived on the scene.

Following this meeting, we prepared to cast off and return to our fjord

anchorage for the night. The ice had moved in around the boats and the wind was

still blowing 20 knots complicating the situation. After some problems breaking

clear from alongside we worked out of the pack around the ship and returned to

our nighttime anchorage. It was another night of anchor watches and waiting.

This has been an excerpt from Roger Swanson’s book Into the Ice.

In the next installment Swanson and his crew start sailing home.

Roger Swanson is from Dunnell, Minnesota. He has cruised Antarctica twice,

almost the Northwest Passage and circumnavigated four times.He has received

numerous international awards for cruising and seamanship.