|

Getting There

by Scott Welty

Cruising by Sail Definitions:

1. Repairing your boat in exotic ports

all over the world

2. Long stretches of relative peace and

boredom separated by brief moments of

abject terror

3. Not being able to go the direction

you want to go.

In this article I’d like to deal with

the third definition (while I’m

currently “enjoying” definition #1).

Head Winds

So often we have a decent wind and, sure

enough, it is right in our face for

where we want to go. The sea conditions

are choppy. What do you do?

Motor straight into it with bare poles.

I see many Lake Michigan sailors take

this approach. When they discuss their

day they’ll say, “you know we just

wanted to get there”. I find this the

most uncomfortable attitude to put the

boat in. Let’s face it, these are rotten

power boats by design! A long day of

hobby horsing and crashing the bow

(which is up higher when on the motor)

into the chop is not a fun day. There is

nothing wrong with motor sailing but

let’s not forget the sailing part!

Motor with the main

Two things will happen if you raise the

main and keep the motor on. 1. The

motion of the boat will be calmed by the

damping effects of the main moving

through the air. 2. If you can bear off

a little to keep some pressure on the

main your speed will increase AND your

motion will be even more sailboat like

and less hobby horse like. But we want

to GET there and now we’ve had to bear

off to keep the pressure on. Ah Ha!

Remember, since you are having maybe an

uncomfortable day, you don’t care how

far you sail; or you care how long you

sail. So the question becomes as it

often does in sailing and in this

article: How much direction would you

give up for how much gain in speed?

In this case let’s say that going dead

into it in some chop you are only making

an average of 3 knots. This is not

unreasonable on our Catalina 30. She’ll

do 5+ knots on the motor alone but heavy

chop and head wind will knock this down

considerably.

So we raise the main and bear off until

the main fills and we get some push from

it. Now we want to sail from A to B but

we are going to bear off and sail a new

direction. The new velocity has to have

the same or better ‘velocity made good’

(VMG) to make this worth it.

|

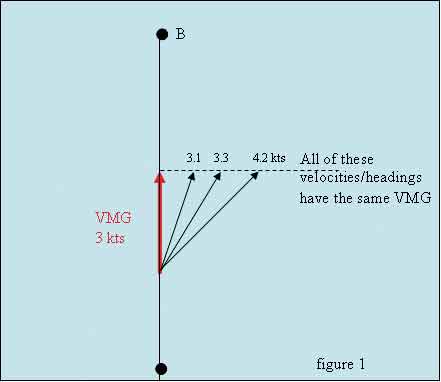

Your VMG is just your velocity projected

back onto your rumb line. As seen in

figure 1, the more you lay off the rumb

line the faster you have to go to have

the same VMG.

|

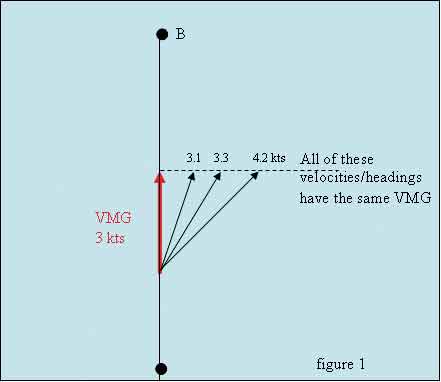

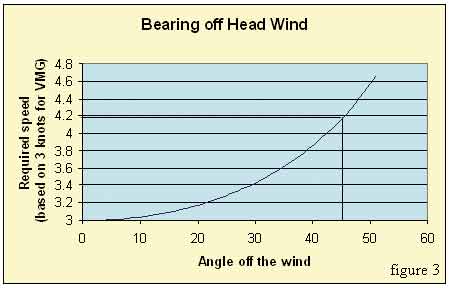

As the graph in figure 2 shows…Raise

your sail and bear off, brother! For

example, if you bear off 20 degrees and

can get your speed up to about 3.15

knots or greater you are going to be

more comfortable and get there in the

same time or SOONER!

|

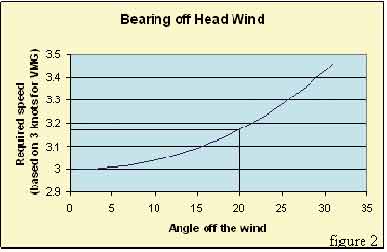

Of course you might turn off the engine

and raise all sails and start tacking in

true sailor fashion, “clawing your way

up the coast” as Hornblower would put

it. Now at the best you are going to be

45 degrees off the wind. It is still the

same graph you just want to look at

angles around 45 or 50 degrees. (see

figure 3)

As expected this requires a more

significant increase in speed to about

4.2 knots but this ignores any leeway.

There is nothing wrong with keeping the

engine on, though! If the boat is in a

more comfortable condition, you are not

pounding into the head seas AND you get

to mess with your sails - go for it! For

me it sure beats the heck out of

chugging straight into the slop.

Sailing Down Wind

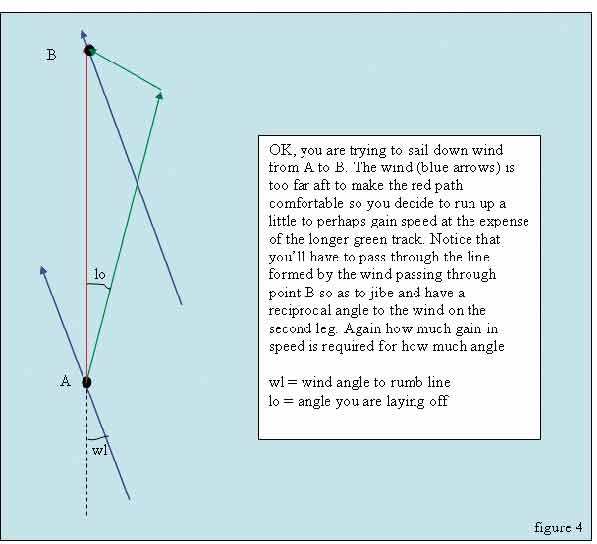

|

The other extreme is being on or close

to a dead run. If you fly a spinnaker or

go wing and wing the question is about

the same. If I’m not so comfortable with

the wind dead aft, but that’s the

direction I want to go, how much gain in

speed for how much I run up? Maybe I run

up until I can get on a broad reach. The

question is geometrically a little

trickier because it is not symmetric as

it is when you are tacking. When you

tack your VMG would be the same on

either tack if you are tacking through

around 90 degrees. When you jibe you

would have a long run on a starboard

tack keeping the wind at let’s say 120

degrees relative to the boat. Then

you’ll have short run on the other tack

to get the wind to be 120 degrees on the

other side of the boat. See figure 4.

|

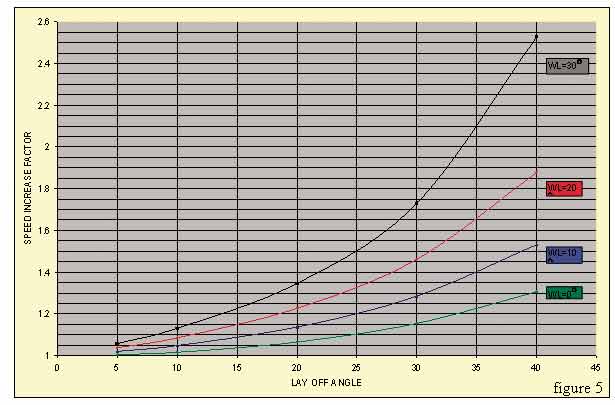

The graph in figure 5 shows by what

factor you have to increase your speed

for how much lay-off angle. Each curve

is for a different wind direction to the

rumb line. For example. If the wind is

10 degrees off of your rumb line (figure

5) and you lay off 20 degrees, you have

to increase your speed by a factor of

about 1.1 times what you were doing

heading right for your mark. So, if you

were doing 5 kts going for it you have

to go 5.5 kts or better to make it worth

it.

What we quickly see from the graph is

that with the wind way behind you, you

are almost certainly going to do better

by running up 5 or 10 degrees. This turn

only requires about a 5% increase in

speed. At 5 knots you have to be able to

increase your speed to 5.25 knots or

better to make this course worth it.

This does NOT take into account time

spent jibing the boat. Certainly the

longer the total run the less this

matters. For cruisers, where a long down

wind leg might be several miles the time

taken to jibe is totally ignorable.

So, cruisers, yes we DO want to get

there but that may mean being a clever

sailor and aiming the boat where you

don’t want to go!

Scott taught high school and college

physics over a 30 year career which

included a 4 year stint at Chicago’s

Museum of Science and Industry. An avid

Lake Michigan sailor, Scott and his wife

Sue Budde retired from their respective

jobs in June of 2005, sold their house,

cars and most possessions and struck out

to try their hand at the cruising life.

Their goal is to get their Catalina 30

sailboat from Chicago to the Florida

Keys and beyond.