Photo courtesy of Billy Black

The Passion of Mike Plant

America’s greatest solo

sailing hero takes his final ride in

Coyote

by Marlin Bree

Copyright 2005

from Broken Seas

|

|

|

Photo courtesy of Billy Black |

|

In a bitter storm on the North Atlantic in 1992, Minnesota racer Mike Plant disappeared under mysterious circumstances in his new racer, Coyote. In an exclusive, Northern Breezes is publishing a five-part serialization excerpted from the new book, Broken Seas. This is Serial 5 of 5 series.

Exactly what happened to Mike and Coyote will never be fully known. His body was never found – and his death probably will remain a mystery of the sea.

Some sailors theorized that Coyote could

have hit something in the water, such as

a sunken container, or even a whale. But

this seems improbable and the report of

the Coast Guard investigation published

in July, 1995, stated that there was

“virtually no significant damage to the

Coyote other than the fact that the bulb

was missing.”

The report went on to say that the fin

showed “no signs of being crushed or

struck by any object. The sides of the

foil showed no signs of impact either.

Finally, the hull itself was intact and

undamaged. Were the Coyote to have

struck a submerged object, the object

would have had to have been at the same

precise depth as Coyote’s bulb.”

Ominously, the report concluded: “It

appears that the only submerged object

that struck the Coyote’s keel bulb was

the muddy bottom of the Chesapeake Bay.”

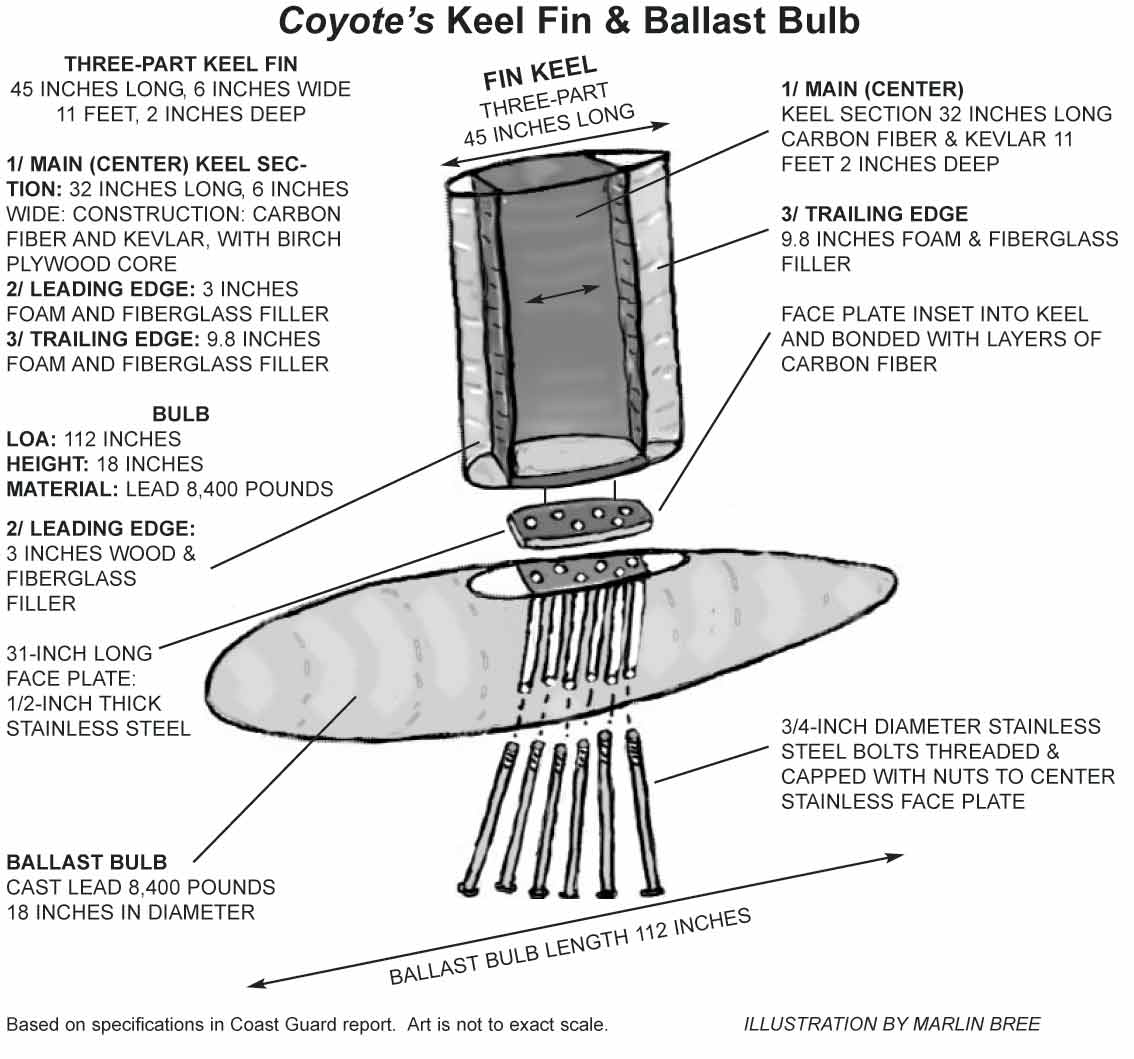

The coast guard report focused on the

design and construction of Coyote’s fin

keel and ballast bulb. With her draft of

roughly 14 feet, Coyote’s hull drew 1

foot 3 inches of water. Her fin itself

was 11 feet 2 inches deep. Below the

fin’s bottom hung the 18-inch-deep

8,400-pound ballast bulb.

The fin keel itself was 45 inches long.

The U.S. Coast Guard’s Marine Casualty

report showed that the fin keel was

basically in three parts: The center

main keel assembly was 32 inches long

and heavily built of Kevlar and carbon

fibers. In addition, the keel had a

leading edge of 3 inches and a trailing

edge of 9.8 inches. The front and aft

edges were of relatively soft foam and

fiberglass filler construction to give

the foil its shape. The exact foil

length was 44.9 inches. It was about 6

inches wide.

The ballast bulb was 112-inch long and

molded of lead. Originally, Mike wanted

to attach a tungsten keel bulb, which

would be smaller and offer less drag in

the water, but the cost was prohibitive

to him at $80,000. Mike had to settle

for a lead bulb that cost $10,000.

Though the ballast bulb snugged up to a

plate on the 45-inch long fin keel, it

actually relied for its fastening

strength on the center 32-inch-long main

keel assembly, the Coast Guard report

pointed out. It also said that this

arrangement gave the 112-inch long bulb

an enormous leverage upon a short span

as Coyote pounded through heavy weather.

In the racer’s drive across the stormy

ocean, the fin must have had tremendous

forces upon it.

The foil emanated a humming noise and a

vibration that Mike and other

crewmembers aboard Coyote could hear and

feel during tests, the Coast Guard

Report noted. It reported that a number

of individuals looked at the keel’s foil

and bulb through the Coyote’s sight

glass while the vessel was underway, but

“none of those persons, however,

reported seeing any movement of the keel

or bulb as the vessel worked in the

seas.”

The report concluded on this point that

“the effect these vibrations had on the

joint securing the bulb to the foil is

unknown.”

The two groundings in Chesapeake Bay’s

mud, however soft they may have been,

drew the attention of the Coast Guard

investigation: “The grounding that the

Coyote experienced in Chesapeake Bay was

probably the single largest contributing

factor to the loss of the vessel’s keel

bulb.”

It explained that efforts to free the

vessel while it was stuck in the bottom

“resulted in the bulb being twisted and

dragged through the mud. In addition,

the entire weight of the vessel shifted

across the bulb while the vessel was

aground. The vessel originally grounded

with a 15 – 18 degree list to starboard.

The Coyote tacked and began to list to

port, but remained stuck in the mud. As

the vessel tacked the list changed from

starboard to port. This caused the

weight of the hull to momentary shift

across and be partially supported by the

keel as the vessel ‘flopped’ from an 18

degree list to starboard, through the

vertical and then over to a list to

port.”

The report concluded that “the

112-inch-long lead bulb extended 34

inches forward of the foil and 45 inches

aft of the foil. The twisting and

dragging of the bulb, and the shifting

of the vessel’s weight across the keel,

most likely weakened the 31-inch joint

that fastened the bulb to the foil.”

“At the time of the grounding,” the

Coast Guard report said, “none of the

parties aboard felt that it was serious

enough of an incident to require that

the Coyote be hauled out of the water or

to have the keel inspected. The

Concordia project manager, however, did

feel the incident was serious enough to

conduct an internal examination of the

vessel. The responsibility for deciding

whether or not to dry dock the Coyote

after the grounding was Mike Plant’s. He

did not have the vessel dry docked, nor

did he have any divers examine the keel.

Considering the fact that the keel was a

new design, it would have been prudent

to have the vessel inspected after the

grounding.”

The Coast Guard noted that “the fact

that the vessel was not launched until

September of 1992, due to financial

delays, probably influenced Plant’s

decision not to dry dock the vessel. He

was on a tight schedule from the day the

vessel was launched through to the day

he departed New York City for France.

His schedule did not allow for

unanticipated delays such as hauling the

vessel out of the water.”

|

Though the fin keel itself survived the

capsize and was recovered with Coyote,

the ballast bulb was missing. The Coast

Guard reported that Coyote’s bulb was

fastened to a stainless steel faceplace

that was about ½ inch thick and had six

holes cut into it and threaded. Each

hole had a ¾ inch nut welded into its

bottom. Stainless steel bolts came up

through the ballast bulb into both the

threaded faceplate and the nuts, for a

minimum of 1½ inches of threaded steel.

The Coast Guard report said that an

overlap laminate of 15 layers of carbon

fiber helped secure Coyote’s plate to

the base of the keel. The report also

said that Mike was “comfortable with the

design and felt it was satisfactory.”

When Coyote was recovered, the Coast

Guard noted, “There was virtually no

significant damage to the Coyote other

than the fact that the bulb was

missing.”

The Coast Guard stated that that “the

loss of the Coyote’s keel bulb was a

failure of the carbon fiber materials

used to secure the 8,400 pound bulb

assembly to the base of the keel’s foil.

When the material failed, the bulb

assembly – which included the lead bulb,

the keel bolts, and the stainless steel

plate – dropped off of the keel and the

Coyote capsized.”

Toward the end, Mike probably was at the

helm, sitting in the dark beside his big

wheel. It was after midnight on the

stormy North Atlantic and the seas were

rough. Black waves big as islands roared

toward him.

He probably was running on the last of

his adrenalin reserves, taking pride in

his big racer’s handling and speed. It

kept him going. He had been hand

steering for days on end and he probably

was having a terrible time keeping awake

and concentrating – yet he knew he could

not sleep. Though he was toughing it out

mentally, he was physically probably

almost overwhelmed by a combination of

fatigue and cold.

He was probably telling himself he and

his boat could make it if they’d just

hang in there. He’d hand steered for

days before. Ahead lay port – he could

sleep then.

His boat was ripping along, tacking hard

into the wind, her sails sheeted in

nearly flat, her mast and rigging taking

a lot of pressure, despite being deeply

reefed. Mike had reefed down to the

third reef in his mainsail, putting up

only 444 square feet of sail area. The

big forward genoa was furled and he was

tacking with his relatively tiny

250-square-foot storm jib. Perhaps he

was thinking of powering down some more.

Coyote’s hull was probably working hard,

slamming through the oncoming waves with

water rushing over the lee rail. Shock

was being transmitted throughout

Coyote’s long hull. Mike heard and felt

it with every jolt in his tired and

bruised body.

Reconstructing the final moments, it

seems apparent that Mike was pretty much

on course and sticking to his intended

route east to France.

Below the hull, immense forces were at

work. As the relatively flat hull

pounded up and down, the 8,400-pound

bulb ballast and keel fought to keep the

giant racer upright. As Coyote crashed

into the faces of oncoming waves and

fought to raise her bow, there were huge

twists and pressures on the end plate.

The noise and vibrations probably were

worse than ever. There might have been

other warnings Mike would have felt

earlier, had the boat not been moving so

quickly or making so much noise with her

battle with the storm.

Or if he had not been so fatigued.

It was not as if he had a choice: he was

nearing the middle of the stormy North

Atlantic and he probably felt his safety

and refuge lay dead ahead. He had to

push on to the best of his ability and,

like other sailors, keep the faith that

his boat would hold together. He had

fought against the odds before and he

had won.

He had water ballast in the port ballast

tank to help stabilize the boat on its

low port tack, probably heading off at

speed through the waves. Coyote did

everything at speed.

Coyote’s sails were loaded up when he

felt a different sort of motion. The

hull vibrated badly. Suddenly, the deck

slammed under his feet.

From somewhere below, there was a final

cracking, shattering noise.

A shuddering probably shot through the

hull. The damaged carbon fiber holding

the bulb plate had finally worn through

and snapped, with a bang-like noise. The

ballast bulb, along with the keel bolts

and the stainless steel plate, dropped

off the base as a single unit.

When the ballast weight was released,

Coyote’s hull bounced up a little. She

probably went off course, began to slow

and heel over.

Dark, green water began marching up her

leeward rail.

The pressure of the wind and oncoming

waves were too much. The beamy hull

probably slowly reared up on its side.

Coyote became quiet, almost eerily so.

She hung there for a minute, then went

over, hard. Still on a port tack, her

long boom with reefed sails caught in

the water, then swung back viciously

toward the boat’s centerline. The boom

cracked under the pressure, broke off,

and was swept back. All that remained

was the first two feet where it was

attached to its gooseneck near the base

of the mast.

As the tip of her 85-foot mast speared

the water, it began to bend and finally

snapped several feet above the deck. It

slammed back against the cockpit,

crushing the top of the cabin doghouse.

The broken mast then trailed below the

overturned hull, held by the stainless

steel rigging, sails still hanked on. In

the capsize, gear had gone flying.

Fatally wounded, Coyote came to rest

upside down, her desperate battle to

cross the North Atlantic over. All was

quiet, save for the sound of the wind

and the waves.

Exactly what happened to Mike Plant that

dark night on the North Atlantic remains

one of the enduring mysteries of the

seas. Had Mike been uninjured and able

stay with his boat, or, if he had been

pitched in the water and able to swim

back to Coyote after the capsize, she

would have sheltered him.

Even overturned, her bottom floated high

on its five airtight chambers and there

would have been more than sufficient air

pockets to live under. Probably, he

could have fashioned the underside of a

bunk to keep him out of the water, just

as other survivors of a similar capsizes

had done. He had provisions and survival

gear on board and the hull rode high on

the water.

Not an organization given to

speculation, the Coast Guard succinctly

concluded its report in this manner:

“Mike Plant probably was killed when the

vessel capsized.”

The report added that, “Had he survived

for a period of time afterward, he would

have remained with the vessel and marked

the hull in some fashion to indicate he

was inside – such as by putting a rag

through the sight glass in the hull. He

also would have tethered the EPIRB to

the vessel to prevent it from drifting

away and inflated the life raft to be

able to get out of the water. The water

temperature in the area where the vessel

was located was 55 degrees F. Survival

time for a person submerged in water of

this temperature is less than 2 hours.

Had Mr. Plant survived the vessel

capsizing, it is unknown if he would

have survived until 22 November 1992 or

if he would have succumbed to exposure.

“Because it is unknown where or when the

vessel capsizing occurred, the weather

at the time of the capsizing is also

unknown. The onscene weather on 26

November 1992 consisted of 25-knot winds

and 5 – 7-meter seas. This weather may

have been a lingering result of the

storm, which passed to the north 3 weeks

earlier. Whether Mike Plant was in the

vicinity of the storm or if the weather

additionally contributed to the casualty

is unknown.”

On October 27, the day Mike is presumed

to have been lost, his EPIRB emitted

three short bursts before it was forever

silenced and lost. The unit was never

recovered when the overturned vessel was

found and inspected in the water. Like

most racers, Mike had mounted his EPIRB

inside the vessel’s cabin on the

starboard side so that a boarding wave

would not knock it off the boat from its

manual release or, worse, set it off. It

would be handy, but he’d have to reach

inside the cabin to activate it.

Why did it only emit an incomplete and

misleading signal? Sailors give varying

rationales on why this happened. One is

that in the moments he had left, Mike

sensed something was fatally wrong and

in the darkness, reached for his EPIRB.

He pulled it out of its holder and

managed to trigger the switch. One

blink, two, three – only to have the

disaster cut his signals short.

The second explanation offered is that

the EPIRB was knocked out of its mount

during the capsize and had only a few

seconds to emit a few signals before it,

or its antenna, was smashed by falling

rigging or the overturning hull.

Most sailors feel the only way for an

EPIRB to go off is for someone to set it

off.

The Coast Guard report says: “..when the

vessel was recovered in January of 1993

– approximately 3 months after the

capsizing – it was noted that the manual

release on the mounting bracket had been

opened, but the hydrostatic release had

not. Whether this was opened by Plant or

somehow knocked loose by debris awash in

the Coyote’s cabin after the capsizing

is unknown. If Plant did not release the

EPIRB, then it probably remained inside

of the Coyote’s cabin for some period of

time until it was eventually washed out

as the vessel worked in the seaway. This

could explain why the device failed to

operate properly.”

It was over coffee at the Minneapolis

Boat Show that I again met up with Capt.

Thom Burns and we began discussing Mike

Plant and his final hours. The ex-naval

officer told me he believed the scenario

went something like this:

“The bulb fell off the boat and the boat

went over probably to 80 or 90 degrees

at first. Mike pulled the EPIRB out and

whatever else he could grab as the boat

was going turtle, probably in less than

a minute. The EPIRB fired off a few

signals before it was trapped under the

boat. Mike may have been trapped there

also or just been unable to get back on

the overturned hull or in it. The hull

composite would not sink, which kept the

boat afloat in an ‘awash’ state. But

Mike was in an exhausted state from

manually steering hundreds of miles, so

his probability of survival was greatly

diminished from both the catastrophic

event and his physical and mental state

of exhaustion.”

There is another mystery to unravel,

that of the critical loss of power on

about the third day at sea which

rendered Mike’s autopilots, computers,

and, radios useless. The Coast Guard

report analyzes this with guarded words:

the “cause of the vessel’s loss of power

is not known, but it appears to be

linked to a failure of the manual backup

control for the voltage regulation

system while Plant was underway.”

It adds that the supplier of the

equipment had recommended that a new

manual control for the backup voltage

regulation system be installed on

Coyote. “The new system was not

installed,” the Coast Guard report says,

“even though the parts were delivered to

the vessel in New York prior to the

beginning of Plant’s voyage to France.

The decision to forgo installation of

the new system was probably based on the

time constrains which were being felt by

Mr. Plant.”

A contributing factor to Coyote’s power

failure was that the engines that drove

the alternators were “underpowered for

the demands placed upon them. This fact

necessitated the installation of the

complex voltage regulation system.”

In the drama of man against the sea,

Mike was a realist. He had been through

a capsize before in the Indian Ocean, in

chill waters, and, he had survived.

Capsizing was not high on his priorities

of dangers. Instead he felt that “the

worst thing that could happen is hitting

something. But I really don’t think

about the boat ever sinking.”

He was correct: Coyote never sank.

Epilogue

On January 26, 1993, Coyote was again

found. Incredibly, she had drifted to a

position about 60 miles south and west

from the Irish Coast. To bring her in,

the tug Ventenor secured towing lines to

the overturned Coyote’s foil and to both

of her rudders. Ignobly, Coyote was

towed stern first to Cobh Harbor in Cork

County, Ireland. Reports say that the

inside of her hull had been pretty much

gutted by wave action.

A Post Casualty Inspection, as contained

in the Coast Guard Report, said that

Coyote’s two forward forestays, which

had self-furling foresails, appeared to

be in the furled position. The back

forestay, also known as the “baby stay,”

contained the tack of the storm jib

which was, the Coast Guard reported,

“all that was left of the sail.”

The report stated that water ballast was

found in the vessel’s portside water

ballast tanks. It concluded, “The fact

that the storm jib was flying, that the

self-furling sails were furled, and that

the water ballast was in the port

ballast tanks, indicates that the Coyote

may have been sailing in heavy weather

on a port tack when it capsized.”

It added, “An equally likely explanation

for Plant’s using the storm jib is that

the autopilots were not functioning due

to the power failure. This would have

required Plant to steer the vessel

manually. Flying the storm jib would

have made the Coyote easier to handle

and less fatiguing over the duration of

the voyage.”

She was hauled aboard a freighter for

her trans-Atlantic trip back to the U.S.

There were no cheering crowds to greet

her arrival back in the U.S.

Though Mike never knew it, insurance for

Coyote had been approved while he was at

sea.

News reports told of surveyors checking

over her hull. Incredibly, after months

adrift on the open Atlantic, she was

pronounced sound after extensive

ultrasound testing, but to add

additional stiffness, designer Rodger

Martin added an interior skeleton of

carbon fiber tubing. She got a lighter,

more streamlined deckhouse, a bowsprit,

and a reconfigured rig to carry more

sail area as well as a new keel and

bulb. In the rebuild, she got even

faster after shedding about 1,000 pounds

of weight.

On Aug 28, 1994, she was returning from

her first major voyage after being

rebuilt when she collided with a fishing

boat. Coyote’s strong hull was

reportedly undamaged, but the 62-foot

fishing boat began taking on water.

Coast Guard planes dropped pumps to

crewmembers to keep flooding under

control.

Undaunted, she returned to racing. With

David Scully as her skipper, Coyote

finally got her around-the-world run.

She successfully circled the globe in

the BOC 1994-95 race and came in fourth.

With an admirable total time of 133 days

56 minutes and 35 seconds, she averaged

8.21 knots.

She placed second in her class in the

1996 Europe One Star Transatlantic Race.

Mike’s family established the Mike Plant

Fund at the Minnetonka Yacht Club to

help underprivileged children

participate in sailing programs. Each

year, kids from throughout the area

learn to sail in the same waters that

Mike sailed on as a boy.

On September 6, 2002, in a ceremony held

in Newport, Mike Plant was inducted into

the Museum of Yachting’s Single Handed

Sailor’s Hall of Fame.

His friend, Herb McCormick, said at the

dedication ceremonies:

“One of the great tragedies of Mike’s

passing is the awful timing. Here he

was, finally, after three

circumnavigations, truly ready to

contend for the crown. If all went well,

if he had that mix of luck and execution

required of all champions, he was ready

to challenge the best on his own terms.

He was ready to live his biggest dream.”

Excerpted from Marlin Bree’s new book,

Broken Seas: True Tales of Extraordinary

Seafaring Adventure (Marlor Press,

2005). Visit his web site at

www.marlinbree.com.

Continue The Vision

The Mike Plant Memorial Fund was established to provide a sailing experience for

inner city kids. Donations can be made to:

Mike Plant Memorial Fund

in care of the Wayzata Sailing Foundation

P.O. Box 768

Wayzata, MN 55391

Visit www.wayzatasailing.org/mikeplant for more information.