|

| The authors |

The

St. Lawrence River:

Pathway to the Canadian Maritimes

By Jim Hawkins and Elinor Adams

|

| The authors |

The River

Those who live along the St. Lawrence

River and consider it their primary

cruising grounds move their boats up and

down the river freely hopping the flood

here and the ebb there to get to the

weekend gathering of friends. They will

travel from Quebec City up river through

the Richelieu Rapids to Kingston for

race week. Only weather, and they all

emphasize weather, holds them back. They

know the river and its moods well. If

you can capture one of them for a beer

and conversation take along a note pad.

Most of those interested in gathering

information on transiting the river see

it as merely a path to somewhere else.

Perhaps you are speeding to

Newfoundland, for the jump across the

pond to Ireland. Or possibly the lure of

the Madeline Islands, Nova Scotia, or

even Labrador is impossible to resist.

You may pass down the river only once

never to return again. Everything is new

and the river has its own mysteries. You

do it and then its over. Because of the

evanescent nature of the passage, one

may be tempted to just follow the buoys

and get on with it. The goal of this

report is to eliminate unnecessary

mysteries of the river so you may be

safer and truly enjoy your transit.

An imaginary line between Kingston, ON

and Cape Vincent on the American side is

often considered the start of the river.

Most sail-boaters coming from the west

will likely want to begin their

experience of the Thousand Islands in

the Canadian Middle Channel and one way

or another work in a stop in Kingston

possibly via the Bay of Quinte or with a

pause at Main Duck Island on the way up

from a New Your port. Unless you are in

a huge hurry to get east, dallying a few

days in the Islands is worth it. (For

those coming up from points south by way

of Lake Champlain the river “begins” at

Sorel at the mouth of the Richelieu

River.)

It is in the Thousand Islands that you

will first begin to feel the power of

the river as a current of about a half

knot is noticeable. And as you leave the

Islands via the Brockport Narrows, the

current increases for a short distance

to as much as three knots. In general,

you can expect the current under your

keel to gradually increase. The current

boost adds many miles of distance made

good to your boat’s normal speed per

day. It makes rushing through the river

possible, may even make it mentally

difficult to slow down.

|

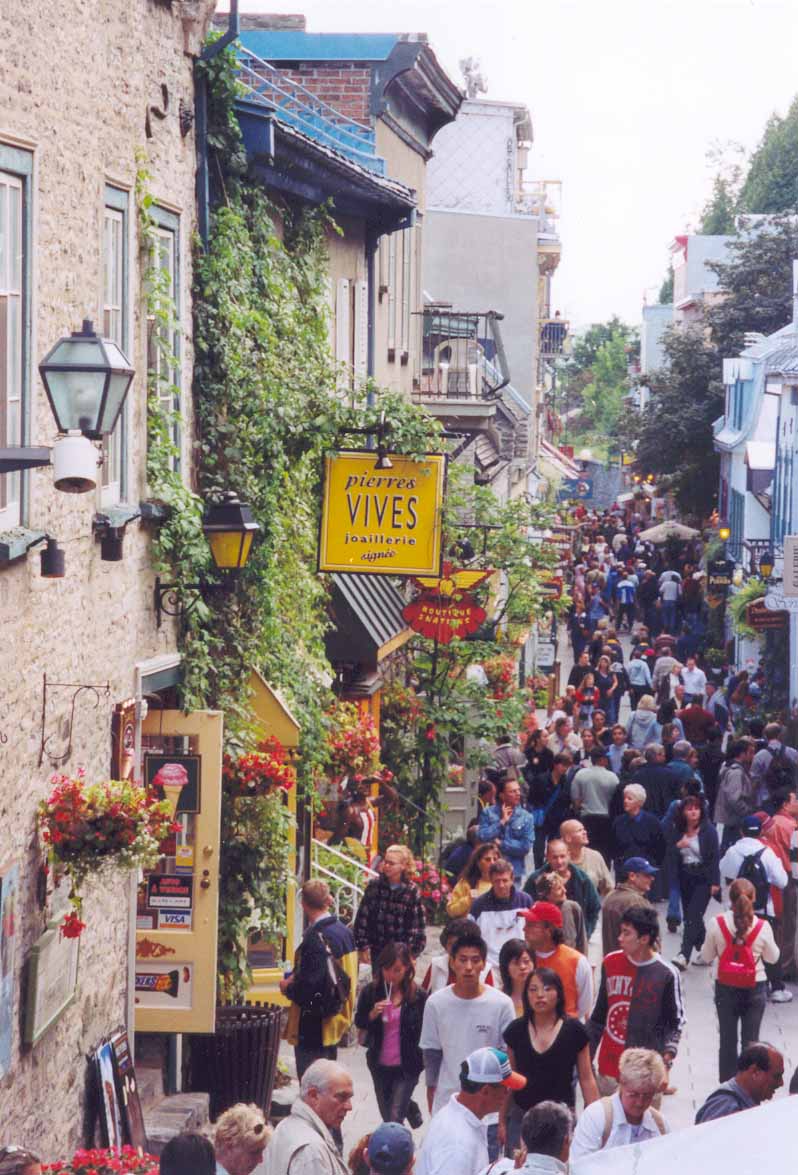

| Quebec harbor marina with old city nearby. |

The river is often quite wide, but as a

sail-boater, you will find the river

oddly constraining despite the added

boost from the current. With the current

carrying you along, you will be able to

put up your sails even if you are able

to sail at only three knots. Sailing in

each of the “lakes” is even likely given

the prevailing westerly winds. But you

may feel controlled by the river as

indeed you are. The depths outside the

channel are often quite shallow. Few

will want to take much of a chance

leaving a buoy on the wrong side. In

some areas the edges of the channel are

rock, not mud. You may quickly have to

douse sails and turn on the engine if

the wind is not just right so that you

can make the next twitch in the channel.

It can be mentally disconcerting and

wrongly, I believe, cause you to use the

engine more than necessary.

You will develop the habit of ticking

off each buoy as you pass, especially

where the buoys are spaced far apart.

Even then it is easy to become

momentarily confused when the channel

takes a jog or a side channel departs

with its own set of buoys. When this

happens, stop, turn on the GPS and get

re-oriented. In some areas the chart

shows a separately buoyed small boat

channel. Satisfactory depths may be

found and the current may be less. It

can be fun and you won’t have to dodge

the big guys.

You will not notice it much, but you are

actually under the control of the

managers of the St. Lawrence Seaway.

They can tell you exactly what to do and

when if need be. You will feel their

presence mainly at the locks. Find out

which VHF channels the lockmasters are

using and you will get a sense of the

Seaway Control. Masters and Pilots of

the big ships are remarkably

deferential.

|

| The magnificent Frontenac Hotel on the bluff above the old city from the River. |

There are seven locks in this section of

the river. The first, Iroquois, is

simply a leveling lock and may drop you

a few inches to a few feet depending on

water levels in the river. Usually you

just float at idle in the water until

the gate opens at the downstream end.

The next two locks are on the American

side and are the easiest to manage as

they have floating bollards built into

the side walls of the lock over which

you loop your own dock lines. The

remaining locks are Canadian. In these,

the line handlers will drop you lines

with which to steady your boat. As you

are going downstream, the turbulence in

the locks is minimal. You will have more

trouble with the wind whistling down

into the lock pushing the boat this way

and that.

You will be required to wait on the

commercial traffic to clear. This could

take a number of tedious hours. And if

pleasure boat traffic is heavy, you may

be required to raft with other boats in

the lock. At each lock there is a

pleasure craft dock on the side you will

tie up to when in the lock. You can

remain overnight at these tie-up docks

if you arrive later in the day. (The

Seaway handbook lists the locks and

tie-up side so you can prepare.) But

with heavy pleasure boat traffic, there

may be no room at the dock. You are then

dependent on the good will of those

already there to offer a raft up.

Sometimes there is anchoring in 10-20

feet, more often in 30 feet. The

Canadian locks cost $20 each either CN

or US. The American locks charge $20US

or $30CN each. Thus, some attention to

the prevailing exchange rate is wise.

Both countries want exact amounts.

The big boats, there are many of them,

want their half in the middle. You would

be wise not to meet one coming upstream

under a bridge or in an otherwise

restricted channel when the big one is

moving at speed. There will be room for

you both, but the quarter wave bucking

the current can be brutal. So give them

room and go slow after they pass until

the wake has settled down.

|

| The authors’ Baba 30 Meta Fog. |

As one moves farther east and north,

marine services become increasingly

scarce. Fuel, water, and pump-outs are

frequent enough, but repair facilities

are not. From eastern Ontario to Quebec

City the yard most mentioned as full and

complete is the Boulet/Lemelin Yacht

facility (yachts@blyachts.com or 800 463

4571 in Sillery, near Quebec City. The

yard is located in the same basin as the

Yacht Club de Quebec. Reportedly, yachts

from as far upstream as Lake Chaplain

and very far downstream travel there for

repairs or winter storage. At least one

circumnavigating yacht was in repair

there in 2003. Otherwise, there are a

variety of mobile repair companies that

will come to your boat towing a

substantial trailer load of supplies.

Beyond Quebec City, repair facilities

become even scarcer and farther apart. A

mechanical breakdown or an inadvertent

grounding requiring a tow could be

costly. Towing insurance in a

substantial amount is recommended.

Partial List of Anchorages: Thousand

Islands to Quebec City

The guides provide adequate information

on marinas, but offer variable

information on anchorages between the

Thousand Islands and Quebec City. Below

is a list of some anchorages, in order,

going downstream from the Thousand

Islands. We have personally used some of

them, perused others, and selected still

others which appear suitable for

sailboats suggested by other sources.

Anchoring with easy access to Montreal

or Quebec City is almost impossible with

exceptions noted below, but the guides

provide complete information on marinas

close to both cities.

There are many other places to anchor

depending on your ingenuity. However,

without clear reason to the contrary,

you should assume the bottom is rocky.

Anywhere the chart notes a mud bottom in a location with protection is worth a try, but a mud bottom almost always means thick grass and weeds so extra time and effort will be required to retrieve anchors. Where a tributary enters the main river, there may well be a silt outflow offering anchoring possibilities even if the chart itself is ambiguous as to the nature of the bottom.

Downstream of the Thousand Islands, a

convenient anchorage is in Morristown,

NY, across the river from Brockville.

You can anchor there in 10-12 feet

behind the floating breakwater out of

the fairway in mud.

|

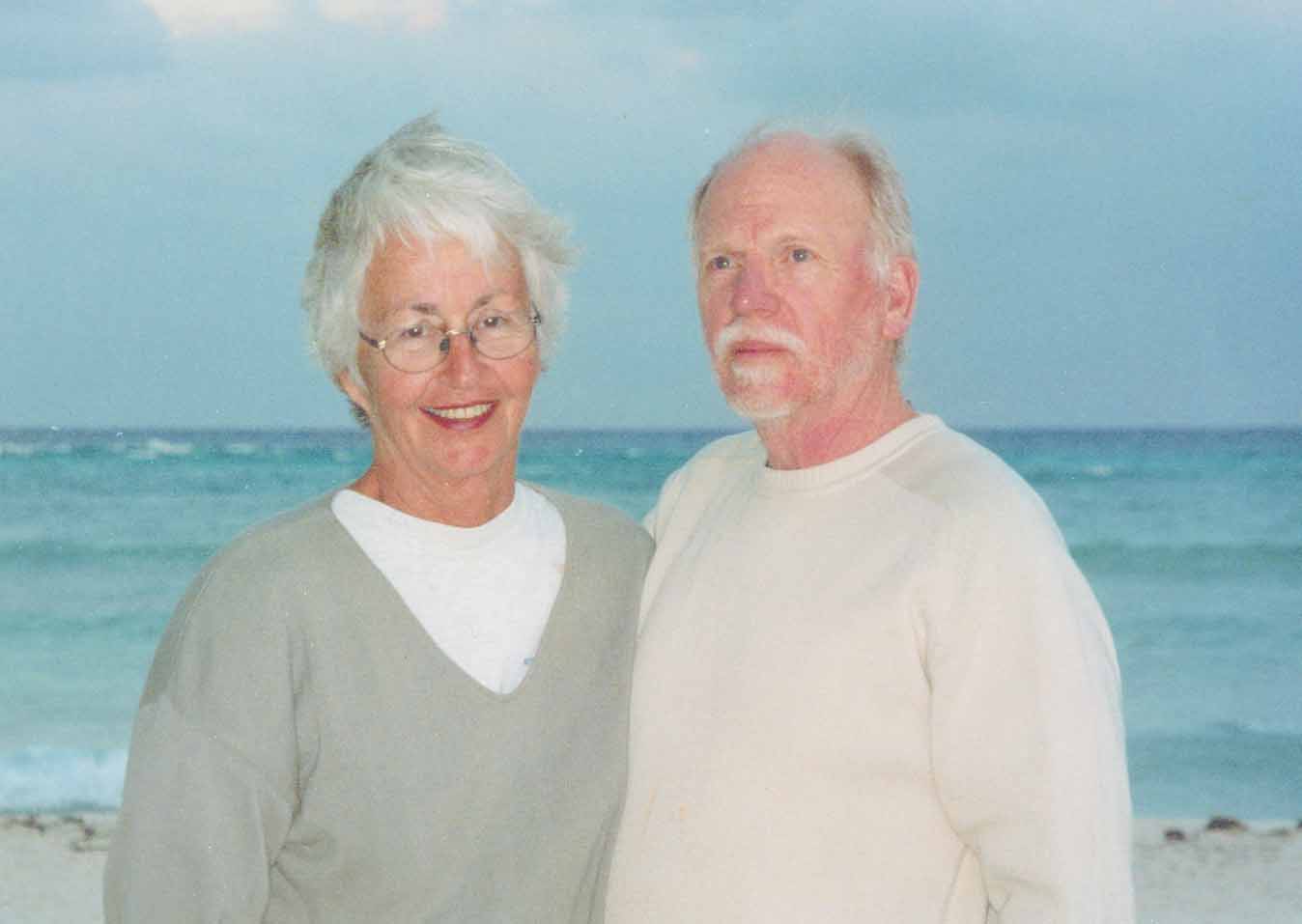

| Tourist group in the old city. |

There are several options as you

approach Lake St. Lawrence. One

convenient option lies NE of the most

easterly of the Croil Islands, about

one-quarter mile north of buoy R50 in

mud.

There appears to be good anchoring near

the east end of Cornwall Island to the

north of Pilon Island. An anchorage

south of St. Regis Island is reported.

Near the lower end of Lac St. Franscios,

is a buoyed secondary channel (shown on

the chart) that leads to the small

harbor of Salaberry-de-Valleyfield. It

offers a pleasant stop before entering

the Beauharnois Canal. The small harbor

is busy on weekends as the parade of

powerboats hurries to the foot of the

bay to round the water fountain and rush

back out. The harbor is open to the SW,

but you can get far enough in to be safe

in summer weather. Here is the first

place where the predominance of French

language speakers is noticed. This

location, about 25 miles short of

Montreal, offers access to the city via

public transportation. The bus station

is a 20 minute walk where you board for

the Agrignon Station, transfer to the

subway, and step off just ten minutes

from the old city. Prior to the return

trip, it is best to relieve yourself as

the Agrignon Station has no restroom

facilities! The marina at Lachine offers

similar access.

Just as you are about to enter the Canal

de la Rive Sud for the long trip around

the Lachine Rapids and Montreal lies Ile

Tekakwitha. South of marker FY is an

anchorage in 12-20 feet, mud, protected

from all but a strong SW. If you intend

to bypass Montreal altogether or if you

arrive late and do not want to chance

finishing the long canal and locks after

dark this is a good place to spend the

night as stopping anywhere in the canal

is not permitted.

You will find a buoyed channel into the

marina at Languiuel downstream from the

Canal de la Rive Sud (past the moorings)

as noted on the chart. Utilize the

channel as if entering the marina, but

turn upstream out of the channel to

anchor near the moorings.

Given the strong current and no more

locks, the stretches from Montreal to

Sorel and Sorel to Trois-Rivieres are

easy one-day ventures. Note, however, a

lovely quiet anchorage lying between low

islands offering good protection about

10 miles north of Montreal. Enter the

anchorage between Ilet Vert and Ile

Deslauriers and round into the channel

between Ile a L’Aigle and the unnamed

islet to the east on the chart. A number

of options farther in are present

depending on the protection you need.

Anchor in 10-20 feet in mud and a

two-three knot current.

A little further along, Skipper Bob

reports on what he calls the best

anchorage between Montreal and Sorel.

Leaving the main channel via the narrow

pass north of Ile aux Rats you can find

sites along the buoyed channel behind

the islands.

The chart shows an anchorage near the

mouth of the Riviere Richelieu, but it

is not protected from current, wind, or

wave action. However, a few miles

further a group of low islands at the

south end of Lac Saint Pierre provide

beauty and good protection. An easy

entry lies north of buoy S130 between

Ile aux Carbeaux and Ile Lapierre, but

there are many options in this group. Be

aware, some of the entries are blocked

with water level control barriers.

At Trois-Rivieres, anchor in the Riviere

St. Maurice to the west of Ile St.

Quentin upstream of the swimming beach

in 10-20 feet. Leave buoy C52 to port

avoiding a rock in six feet reportedly

near the first nine-foot spot on the

chart.

Trois-Rivieres to Quebec City

Beyond Trois-Rivieres the river changes

character as tidal influence becomes

significant. The Richelieu Rapids can be

intimidating, but the main difficulties

(though hardly hazardous) for a deep

draft boat are the rips and boils. With

careful planning you can choose to go

through with a “slow” current, but you

may still register 11 knots over the

ground for a short stretch. At this

point the Sailing Directions ATL 112 and

a tide reference are extremely helpful.

Slack water after high tide lasts as

little as 20 minutes. At low tide, the

current continues to run out slowly for

another hour or so with local

variations.

|

| Looking downstream

from Quebec harbor with

one of many “saltys” in

the view. |

It is possible to cover the 67 miles in

one day: A vessel traveling at six-seven

knots should leave Trois-Rivieres eight

hours before low tide at Quebec. Faster

boats can leave five-seven hours before

low tide while slower boats should leave

nine-ten hours before low tide at

Quebec, but this means a fair amount of

pushing into the flood and/or traveling

in the dark.

A better way for a slower boat, I

believe, is to take two days. For the

fastest passage with time to spare

before the tide reverses, you would

leave Tres Rivieres at local high tide

slack. Portneuf lies about half-way to

Quebec City just past the Richelieu

Rapids. Deep draft boats can enter the

marina at any tide. One boat known to us

anchored just downstream behind the

Portneuf breakwater laying a second hook

into deeper water as a precaution. An

anchorage in eight feet at low tide with

a sand bottom lies directly across the

river and shows on the chart. Anchor on

either side of the old wharf. Locals use

this as a weekend anchor-out spot and

reportedly enjoy the sand beach located

there. Others use it to await a change

in tide. In a pinch, you can tie outside

the Portneuf wharf, but due to the tidal

range you may need to tend lines.

Another good “half-way” option is the

Neuville marina 10 miles further

downstream. Accurate instructions for

entering are given in the Sailing

Directions. When continuing on from this

marina, you may head downstream directly

from the breakwater at any tide by

angling toward the south end of the

suspension bridge visible in the

distance. To move quickly on to Quebec

City, leave at local high tide.

In Sillery, just before Quebec City

itself, anchor among the moorings in

sand adjacent to the Yacht Club de

Quebec. While the current runs strong in

both directions in the channel, it is

much reduced through the moorings To

easily visit Quebec City, take a slip at

the Port Authourity Marina which is only

a ten minute walk from the old city.

Quebec City to Tadoussac

A little way past Quebec City, you

encounter salt water for the first time.

Tidal influence is, if anything, more of

a factor and the river current is still

strong. Most of the marinas, with

significant exceptions, dry at low tide.

Keelboats can enter at half-tide, or

above but sit down in mud when low tide

arrives. In contrast to the portions of

the river described so far, staying in

the big-boat channel all the way is not

the preferred path. For example, Cap-a-L’Aigle,

the first marina with access at low

tide, can be reached in one day by

leaving Ils aux Coudres far to port

while following one of the “old”

sailboat channels. The ebb tide plus the

river current can reach nine knots here

making it feasible for even a slow boat

to traverse 70 miles in a day.

Typically, one leaves Quebec a couple of

hours before high tide and arrives at

Cap-a-L’Aigle before or just after the

flood begins.

Anchorages are available all the way

out, but some are exposed to NE or SW

winds. Timed right, marinas that dry can

be visited. So this 70-mile section of

the river can be covered in one or many

days. Marinas, anchorages, tidal

currents, routes, and cautionary notes

are so well described in “St. Lawrence

River and Quebec Waterways” that

additional advice here would be

superfluous.

Shallows and islands pepper the river up

to Tadoussac contributing to severe rips

and overfalls where the bottom interacts

with swift currents. Rips are further

enhanced due to the outflow of the

Saguenay River, a significant river in

its own right. These complicate a visit

to the whale sanctuary and entry into

the Saguenay fjord. Combining anchorages

and marinas in tandem on both sides of

the river provides many options for

enjoying the river and managing the

demands of wind, tide, and current.

Tadoussac to

Cap Rosiers

Below Tadoussac, you start to feel you

are truly in the ocean. The outflow from

the Saguenay River tends to stay near

the surface as it trends to the south

side of the St. Lawrence. It serves to

keep the south side of the increasingly

wide river warmer while reducing the

already diminished flood all the way to

the tip of the Gaspe’. Still, a strong

east wind against the current can make

for an uncomfortable chop. Cold water

wells up on the deeper north side of the

river, the turbulence enhancing the food

supply for the whales. But the north

side offers more remote and, for some,

more interesting, if colder, cruising.

Careful planning and attention to the

tidal range is still required to assure

access to marinas or anchorages.

Passing out of the St. Lawrence, one is

presented with a bewildering array of

cruising destinations. Turning south

takes you to the Gulf coast of New

Brunswick and on to Nova Scotia. To the

east lay the Isles de Madeline and

beyond them the west and south coasts of

Newfoundland or the east entrance to

Cape Breton. To the northeast the Belle

Isle Strait gives access to Labrador and

the east coast of Newfoundland.

The St. Lawrence River is a cruise in

itself with plenty of excitement and

challenges to satisfy the most seasoned

crew. But the river also opens the way

to some of the most beautiful and, yes,

challenging cruising in the world, the

Canadian Maritimes.

Jim Hawkins and Elinor Adams are

starting their second extended cruising

adventure. Stay tuned.