by David Dellenbaugh

In a steady breeze, you will get to the windward mark fastest if you always sail your optimal angle upwind (with a few tactical exceptions). This gives you maximum velocity-made-good (VMG) to windward for the wind direction that you have for the entire leg.

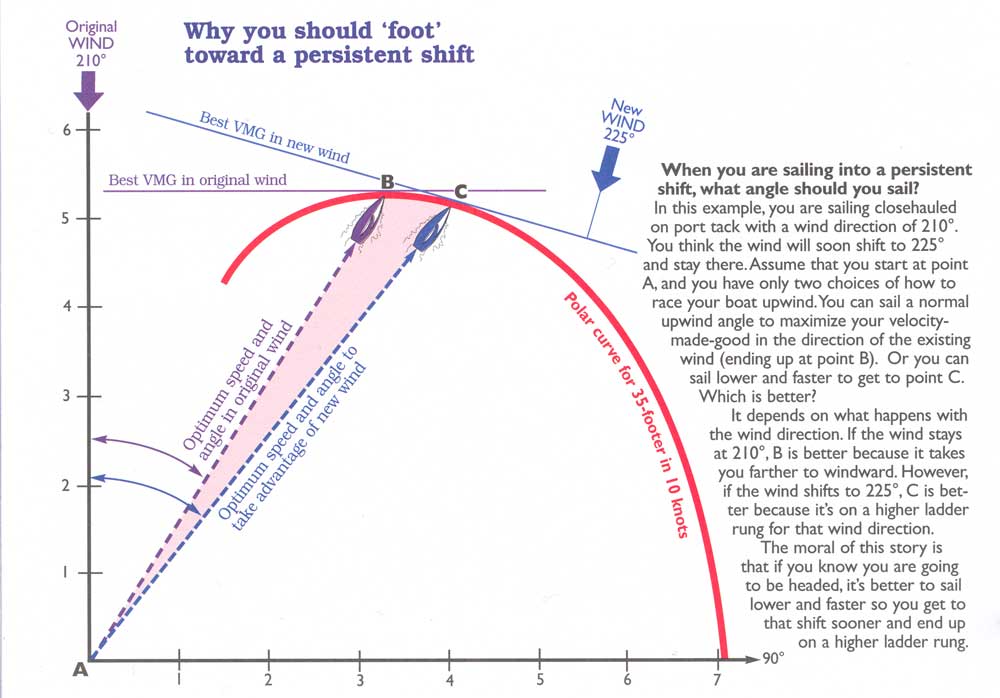

If you expect a persistent windshift during the first beat, however, donít

maximize your VMG for the wind direction you have at the beginning of the leg.

That wind will disappear, so optimize your performance for the wind direction

you expect to have when you round the windward mark.

In order to be on the highest ladder rung when you sail into a header, you

should sail a little lower and faster than normal in the breeze you have before

the shift (see diagram below). Sailing faster helps in several ways. First, you

will get to the new shift sooner. Second, when the wind changes direction you

will be closer to the shift. And third, you will end up farther to windward

(relative to the new wind direction) than if you kept sailing your normal upwind

angle.

|

How confident are you about the wind?

As a strategy, sailing low and fast upwind is a little risky. If the wind

direction doesnít change before you reach the layline, you will have lost ground

to any boats that sailed their optimal upwind angles. You will also lose

distance if the wind direction oscillates or if you tack before you realize the

full benefits of sailing into the header.

Therefore, donít sail below your normal upwind angle unless you are pretty

confident that, before you reach the corner of the windward leg, the wind will

have shifted significantly in the direction you are heading. This confidence

should be based on some thorough research and data you gather using local

knowledge, weather forecasts, wind observations in the course area and so on.

If all your info points to a persistent shift, and if youíre willing to assume a

certain amount of risk, try sailing fast and low. Start conservatively by

bearing off only until your windward telltales fly straight back. If this works,

try going a little further - you may be able to make some nice gains.

|

When it wonít work to sail fast and low

Even when itís obvious that you are sailing toward a persistent shift, however,

there are certain times you should not sail fast and low. Itís better to stick

to your normal upwind angle when:

Youíre fighting for a lane of clear air - It may be important to maintain

your height so you donít fall into the bad air of boats ahead or to leeward.

This is especially true right after the start when the fleet is still close

together and you are trying to hold a lane of clear air on the long tack toward

the favored side.

You may tack soon - If you are thinking about tacking soon because youíre in

really bad air or youíre almost at the layline (or for any other reason), it

doesnít make sense to sail low and fast because you wonít have enough time to

make gains this way. Instead, sail your normal upwind angle until you tack.

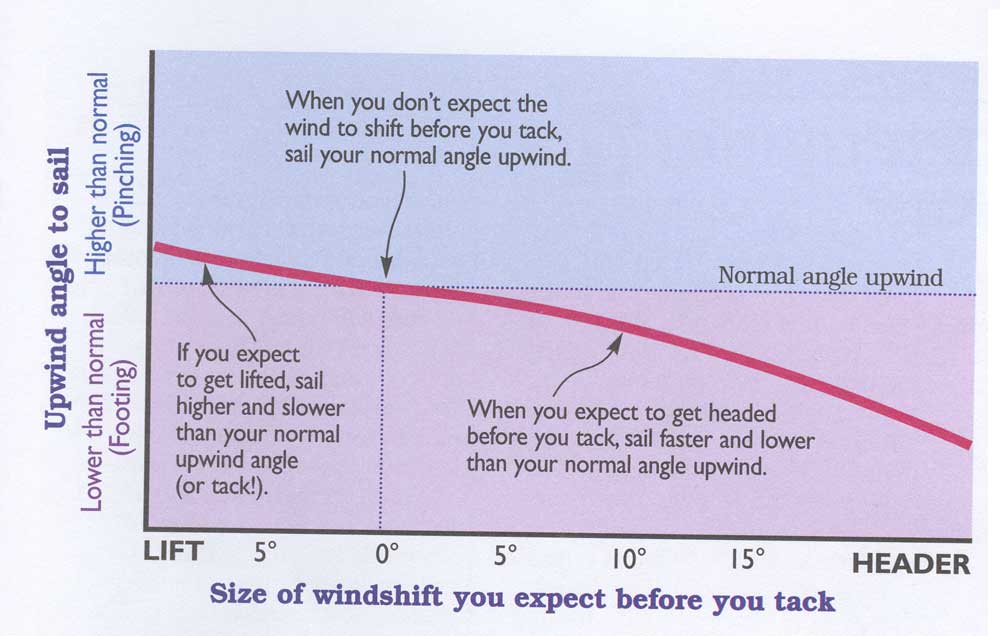

You donít expect a very big shift - Sailing low and fast works best when you

are planning to stay on one tack for a while and youíre anticipating a

significant header. If you expect only a small shift before you tack, you should

probably sail your normal upwind heading. The degree to which you sail lower and

faster is roughly proportional to the amount of header you expect before you

tack (see diagram above).

|

| When you are sailing toward a persistent shift (e.g. a header close to land), it usually pays to sail a little faster and lower than normal. This is particularly true when a) you have a long way to go on that tack; b) you expect to get a significant header before you tack; and c) you have a clear lane and arenít worried about falling into the bad air of another boat. |

Try this on downwind legs

This concept of sailing a different angle works on runs, too, but instead of

sailing toward the expected shift, you should sail away from it. Also, instead

of sailing fast and low, you should go fast and high. This will get you farther

away from the next shift, and will put you on a lower ladder rung (and therefore

ahead) when the wind shifts. As with upwind, the amount you sail higher and

faster should correspond to a) how long you plan to be on the jibe; and b) how

far you expect the wind to shift before you jibe.

One side benefit of sailing a little faster than normal is that you will have a

wider steering groove. Itís hard to keep the boat going at full speed when

youíre trying to point as high as possible and the sails are constantly about to

stall. This is especially valuable when you have lighter wind, waves or an

inexperienced helmsperson.

Dave publishes the newsletter Speed & Smarts. For a subscription call:

800-356-2200 or go to:

www.speedandsmarts.com